"I Asked Bobby Dylan, I Asked The Beatles"

(L-R: Peter Townshend, Ric Burnett (obscured), Greg Biggs, unidentified woman, Janet Caldwell, and Jeff Cochran, backstage at the Omni, Atlanta, Georgia, after a Who concert, November ‘75, photograph by Tom Hill)

There’s a lot on Pete Townshend’s mind — and a lot to get off his chest. His opening guitar riffs to “The Seeker” make it instantly clear. The song, recorded by the Who in January of 1970, is both a plea for clarity and a declaration. Rarely has the search for meaning amidst dashed hopes sounded so triumphant.

“The Seeker” covers well-traveled ground. The back story is a familiar story. An individual accomplishes much. There’s the acclaim, the money and people wanting to know what makes you tick. With an adoring press, Pete Townshend knew all about that. Though less than a year had passed since the release of the Who’s rock opera, Tommy, Townshend was already considered top-drawer. Fans and critics ardently praised the English rocker’s compelling and observant lyrics, all sandwiched between his expressive melodies. Words and music: Pete Townshend knew how to put them across. For those who had followed Townshend over the previous few years, Tommy confirmed it.

Even before the remarkable success of Tommy, Townshend was the rocking firebrand holding forth on teenage angst and garden variety hypocrisies with “Substitute,” “I Can’t Explain,” and “My Generation.” While the Rolling Stones lamented “What a drag it is getting old,” Townshend took the perception a step further, declaring, “Hope I die before I get old.” Combining a healthy resentment for authority figures and how they weaken the young, or just anyone needing a break, Townshend and his mates crafted an immediate classic with Tommy. Attention was paid. Along with John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Bob Dylan, and Brian Wilson, Townshend was granted recognition as a consummate songwriter, who, like the other greats, carried out his musical vision, from the words and melodies in his head to the finished product on vinyl. But even with all the laurels thrown his way, something was bugging Pete Townshend.

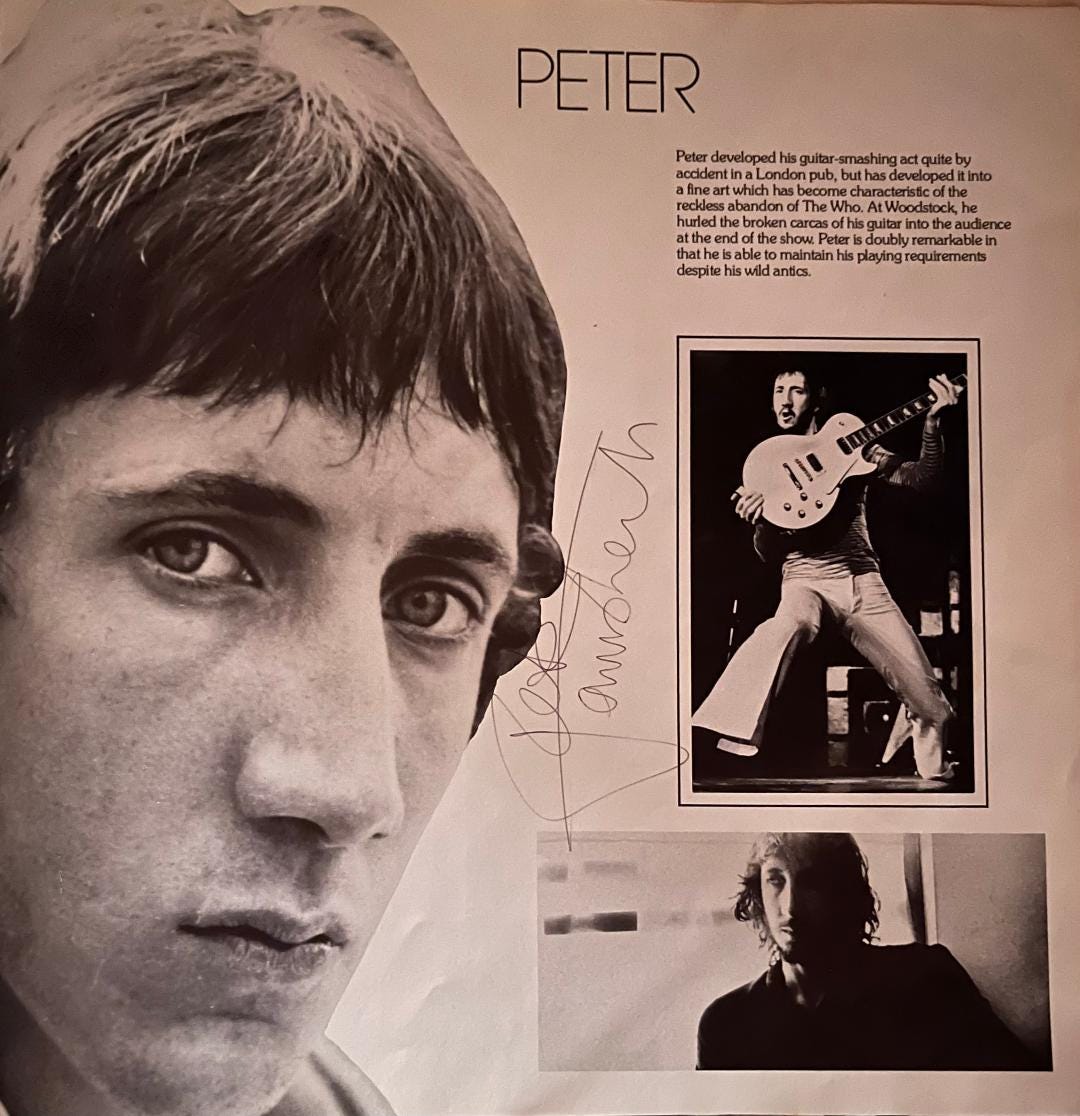

(The Who program Peter Townshend signed for me after the November ‘75 concert)

In the May 14, 1970 issue of Rolling Stone, Townshend told journalist Jonathan Cott “The Seeker” was about what he called “Divine Desperation, or just desperation. And what it does to people.” The narrator in “The Seeker” is consumed with finding the “key to fifty million fables,” all the while making his noble search a dreadful trip for those he encounters. Townshend explained it — sort of — to Cott:

“It just kind of covers a whole area where the guy’s being fantastically rough and ruthless and nasty and he’s hurting people, wrecking people’s homes, abusing his heroes, he’s accusing everyone of doing nothing for him and yet at the same time he’s making a fairly valid statement, he’s getting nowhere and the only thing he really can’t be sure of is his own death, and that at least dead, he’s going to get what he wants. He thinks!”

“I won’t get to get what I’m after till the day I die” goes the refrain in “The Seeker.” Townshend’s narrator sounds both convinced and deflated. There may be peace in the after-life, but that’s incumbent on choices taken before he assumes room temperature. Yet despite the references to knowledge and fulfillment at the time of death, Townshend’s seeker is most interested in right now. Most telling upon its release was how “The Seeker” reflected the viewpoints of young people during that time, many of them expounding on the issue while sorting through the Who’s albums in the record shops. The emerging counter-culture encouraged questioning new ideas about old beliefs. A new perspective was imperative. For example, just because the Selective Service Bureau determined you should report to an Army base and be trained for combat hardly made it right, even if it was the law. Weren’t there far better things to be doing? And for those who didn’t know exactly what the better things might be, they’d take more time contemplating. Looking for truth. Taking time off “to find myself,” or “To determine who I really am.” And “To march to a different drummer.” Still, as admirable as some of their goals might have been, too many young people often seemed to be putting their lives on hold, running away from responsibility, embracing pretensions, even though seeking and learning could still take place as one got on in life. But of course, with the reality of dubious battle so imposing, if one could avoid donning an uniform and being placed in harm’s way, so much the better.

The Selective Service Bureau, the military, and its corrupt war in Vietnam helped bring about confusion and the often aimless direction of tens of thousands of American baby boomers, many who regarded Townshend, then just 25, a sage. Townshend likely laughed at such a notion even as he turned verbal cartwheels in explaining himself at times, although a song like “The Seeker” made things clear enough.

Young people then were aghast at their government officials, and even their parents, all way too eager to send them off to die, supposedly defending their country overseas when society was breaking down back home. The justification for the war contributed to the mental clutter of the day. More questioning and rejection of core values followed. Kids brought up Baptist and Methodist found solace in the teachings of old bearded men in the Himalayas and other distant retreats. Eric Burdon and the Animals lampooned such seekers in their ’68 song, “Year of the Guru.” Years later Woody Allen poked at the new stream of deities in Annie Hall when his character, Alvy Singer, says, “Look, there’s God, coming out of the men’s room.” There was also the pursuit of God and expansive visions through drugs: a plague that took hold in the Vietnam years. In “Wild Horses,” the Rolling Stones captured the mood, declaring, “Faith has been broken.” Young people in 1970, listening to the Stones, and fearful of their lives being hijacked, sought new truths to embrace, but too often made bad decisions as life passed them by. Heavy hearts shared turf with the hopeful hearts.

“The Seeker” capsulizes the yearning and searching. Townshend’s seeker looks to his rock and roll heroes and a drug charlatan for “the key to fifty million fables.”

I asked Bobby Dylan

I asked the Beatles

I asked Timothy Leary

But he couldn’t help me either

The seeker admits at the end of the song that “I won’t get to get what I’m after till the day I die.” And perhaps the seeker preferred he not die before he got old, whether that “key to fifty million fables” was found or not.

The Who give a celebratory sound to the laments of “a really desperate man” in the 3 minutes and 21 seconds of “The Seeker.” Townshend provides a sprightly guitar break which would have fit in perfectly in a mid-60s Beach Boys hit. On piano, Nicky Hopkins mixes dramatic flair with a honky tonk attitude. And though he found the song ‘cumbersome” and “pretentious,” Roger Daltrey’s vocal performance is terrific. “To sing that song, to me,” Daltrey told Uncut magazine, “was like trying to push an elephant up the stairs.”

Daltrey sells himself and the song short; he pushed that elephant all the way to the top floor. In the last verse of “The Seeker,” Daltrey is going full-tilt, adding fire to Townshend’s lyrics that encompass a generation’s lost ways. Even Gertrude Stein, an expert on lost generations, would be impressed:

I’m looking for me

You’re looking for you

We’re looking in at each other and we don’t know what to do

“The Seeker” made little impact on the American charts, peaking at number 44 on the Billboard Hot 100 shortly after its release in April of 1970. About 16 months later, The Who released Who’s Next, a certifiable classic which would climb to number 4 in the U.S., eventually selling over 3 million copies. Later on that year, “The Seeker” was included in a greatest hits package, Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy, which proved a very popular release for the holiday season.

I Got Values, But I Don’t Know How Or Why . . . The Who played “The Seeker” on their U.S. tour in 1970 but set it aside for three decades before reviving it for their numerous reunion tours. But the song never seized the moment as it did in American Beauty, the 1999 film that chronicles the last year in the life of one Lester Burnham, an affable baby boomer scorned and slighted by employers and family members. Lester, played brilliantly by Kevin Spacey, doesn’t take his responsibilities as seriously as others think he should. The boom is lowered on Lester. At work. At home. So he decides it’s time to take his own life seriously, never mind the proper protocol. And though he isn’t a seeker, for inspiration, he looks back to the cultural touchstones of his youth.

The responsible adult life was bearing down hard on Lester. Somewhere along the way, marital bliss with Carolyn (played by Annette Bening, who marvelously takes shrillness to new levels) turns into Marriage Incorporated. Then it’s a spousal detention center. Fatherhood, once a source of joy, now diminishes him. His daughter, no longer his best pal, considers him a loser. His employers of 14 years find him unnecessary. Lester Burnham has been stationed at rock bottom long enough. There’s nowhere to go but up.

Lester’s 42 and looks healthy enough, but he wonders how long he’s been dead inside. The slights exacted by those he loves and those he tolerates have taken their toll. As the slights pile up, Lester becomes more submissive. He sits in the back seat of his wife’s car as she drives him to work — and he appears to belong there. The days when Carolyn would join him in a back seat or some other cozy place are ancient history. Those days can’t be reclaimed, yet the spirit of days-gone-by can be. So Lester gets behind the wheel just as the spirit is firing on all cylinders.

As far as Lester’s concerned, there’s nothing but blue skies from now on. He gets fired, but he doesn’t leave the office until he successfully extorts his boss for $60,000. He then gets a job flipping burgers at a fast food restaurant because he’s looking for the least amount of responsibility; that way he can devote more time to smoking grass and lifting weights while listening to Dark Side of the Moon. He trades in his Camry for a 1970 Pontiac Firebird, the car he always wanted. Now he rules. His weightlifting regiment is progressing handsomely. His daughter’s best friend, Angela, the 17 year-old fantasy goddess, who he overheard saying he’d look great if he’d add some muscle, has taken notice. Lester’s so jazzed over Angela’s come-ons that he’s hardly fazed by his wife’s morning workouts with the king of real estate at a low-rent love nest. Lester Burnham’s regression has taken hold and he feels fine.

Fit as a fiddle and ready for love, Lester hits the pavement. It’ll be his last morning run. After all, it’s going to be his last day on earth. Lester acknowledges as much in a voice-over while “The Seeker” makes it cameo appearance. Townshend’s spirited guitar riffs — quick and snappy — seize the viewer’s attention. The riffs proclaim pivotal moments are ahead. The film’s director, Sam Mendes, and screenwriter, Alan Ball, created grand opportunities and moral dilemmas to fill Lester’s last day. He might get to get what he’s after — on the day he dies.

Those watching American Beauty have to come away disheartened by Lester’s untimely exit. He met a bloody end just as he finally learned to embrace the beauty of the world.

Focusing On Nowhere . . . In his early 40s as the 20th century gives way, Lester Burnham was born too late for the draft or to attend the pop festivals. He was too young for the angst and thrills most baby boomers experienced or at least observed. But he was likely exposed to guys like Pete Townshend’s seeker. The drug scene didn’t disappear with the Selective Service Bureau. With Vietnam and Watergate behind us, we still had to cope with the debris of a generation. Upon returning home late one night from seeing Slaughterhouse Five, a friend of a friend sat in the backseat, looped on something, talking about the search for peace. Then he started to babble about Georgia’s Stone Mountain, where the images of Confederate “heroes” of the Civil War are carved on its rigid north face. Stone Mountain, as identified with the Ku Klux Klan as any place in America, was where our addled friend found peace and comfort.

As great as “The Seeker” comes across on American Beauty, it’s obvious throughout the film that Lester isn’t seeking greater truths. Basically, he just wants what he knows he’s earned but let slip away over time. If he has to replace his indifferent wife with the 17-year old fantasy goddess, it’s just something he’ll have to deal with. Obviously, Lester’s desires are far less pure than those of Larry Darrell, the protagonist in W. Somerset Maugham’s 1944 novel, The Razor’s Edge. Larry comes home alive and kicking from World War I because of a fellow soldier’s bravery. The soldier lost his own life in saving Larry and the survivor is forever and profoundly moved by the sacrifice. Jesus Christ, who would feel the pain of denying one’s self, told his followers, “Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends.” Perhaps such thoughts resonated with Larry, knowing there was more to life than lavish parties or the comfy executive positions available to him. Larry Darrell becomes a seeker.

Somerset Maugham wasn’t seeking when he journeyed to India. He was gathering material for The Razor’s Edge. It was circa 1937. Maugham observed a young man named Guy Hague, an ex-sailor from Long Beach, California at the ashram of Ramana Maharashi. Hague had been on a spiritual journey, seeking peace, seeking fulfillment. He found it in the presence of Ramana Maharashi, often called the Bhagavan, meaning “Lord.” Hague found peace and it’s likely Maugham found models for his own creations, Larry Darrow and the holy man Darrow would seek out on his journey to India.

Maugham allowed space for a famous writer named Somerset Maugham to narrate The Razor’s Edge. The fictional Maugham is also a character in the novel, serving as good company, a friend always willing to lend an ear and happy to spring for dinner and drinks. Ostensibly, the novel is about Darrow’s seeking to find fulfillment in life, looking for the answers men have sought over one millennium after the other. But in a sense, given Darrow’s humility and expressions of friendship to those needing support, one gathers he had long carried life’s answers with him, even before his search took him from Chicago to France, Germany, and finally, India, before meeting up with his old friends again in Paris. Darrow learns that even with the answers, pain and tragedies touch one and all. But he did know how to navigate the hardships and be ready for the next challenge or simple act of kindness.

As absorbing as the novel is, the film adaptation of The Razor’s Edge far better conveys the story of Larry Darrow. Tyrone Power portrays Darrow with brio and a radiant heart. Power, at his tall, dark, and handsome best, senses Darrow’s innate goodness and ongoing penchant to learn more. The film audience is assured Darrow would always be “seeking low and high,” having a wondrous time all the while.

We All Know Success . . . A few years before he wrote “The Seeker,” Pete Townshend was introduced to the teachings of the Indian guru, Meher Baba. Though not immediately, Baba’s words clicked with Townshend. He became the best-known follower of Meher Baba in the western world. In the November 26, 1970 issue of Rolling Stone, he wrote a lengthy tribute to Baba, acknowledging his faith in the Indian mystic, though he admitted that “writing a piece like this makes me feel like a miniature Billy Graham.” Townshend noted how he never met Baba or even exchanged letters with him (Baba died, age 75, in 1969), but in his travels with the Who, especially in the United States, other Baba followers treated him as a “Baba Celebrity,” gaining far more attention than even the closest devotees in Baba’s mandala. And of course, this was while Townshend, despite his faith, was knee-deep in the trappings of his own celebrity. The struggles and temptations that come with the accolades were a constant presence, he explainss in Who I Am, his 2012 memoir.

Townshend gives an intelligent and often brutal accounting of his life in Who I Am. Even as his brilliant and riveting music comes to mind — clear as a bell — while reading, Townshend’s recollections are often disheartening. Saddest of all is how he let down his wife, Karen. There’s no doubt he loved her and he makes it clear she showed him an immense amount of love in return. They stuck it out for the better part of three decades before throwing in the towel, though given his infidelities and mood swings, Karen couldn’t have been blamed for doing so much earlier. In the chapter, Rock Star Fuckup, Townshend offers a snapshot of sorts from 1979:

There was no hiding the fact Karen was getting sick of me, my selfishness, my overwork, my drinking. Some close friends advised me she married a rock star, what did she expect? But that wasn’t it, Karen had grown up, whereas I was having difficulty doing so, in or out of rock.

Certain aspects of Townshend’s life covered in Who I Am are also discerned in “Don’t Let Go The Coat,” perhaps the best song on Face Dances, the Who album released in 1981. The song sheds light on the perils of being adrift and losing contact with what’s important: one’s faith, one’s partner for life and one’s desire to follow through on obligations. That said, “Don’t Let Go The Coat” is melodious and upbeat — it’s downright catchy. The pensive lyrics can be obscured by the song’s optimistic sound. Townshend writes (Daltrey sings) that he “won’t let go the coat.” He’ll figure it out eventually:

So I live my life tearing down the runway

Sure to get the hang of hanging in there someday

Give Townshend credit He’s written a book about who he really is. Sad and painfully embarrassing moments get equal time with his musical triumphs and his efforts to focus on what’s important, like staying close to his children.

Townshend, and the seeker he gave life to in song, possess qualities found in both Lester Burnham and Larry Darrow. Consider Lester’s pluck, adaptability, and humor. Then think of what Larry possessed: goodness, a quality the Somerset Maugham character called the “greatest force in the world.” Given his gentle spirit, Larry already got what was he was after, long before the day he’d die.