If Dogs Run Free, Then Go, Dog. Go!

My wife, a longtime first grade teacher, loves to see the kids and dogs scamper across the yards. There is something to their exuberance; a sense of freedom the kids will fondly remember. “Free your inner dog,” says Gena.

So our mutual interest in Bob Dylan and her efforts to spark the joy of reading into her students inspires us to accept a weekend homework assignment. We listen to Dylan’s “If Dogs Run Free,” recorded in 1970 and included on his New Morning album, released in October of that year. Also considered was an outtake of the same song, released in 2013 on Another Self Portrait (1969-1971); Dylan’s tenth volume of The Bootleg Series. As the music played, Gena read a new children’s book, if dogs run free, with text from Dylan’s song and colorful illustrations by Scott Campbell. Who knew the scholarly life could be such fun?

Campbell has dogs and children frolicking through the fields and by the waters, joined by turtles, frogs, birds, mules and friendly train engineers. “The best is yet to come. That’s what they explain to me,” Dylan muses, making one recall when that rang true.

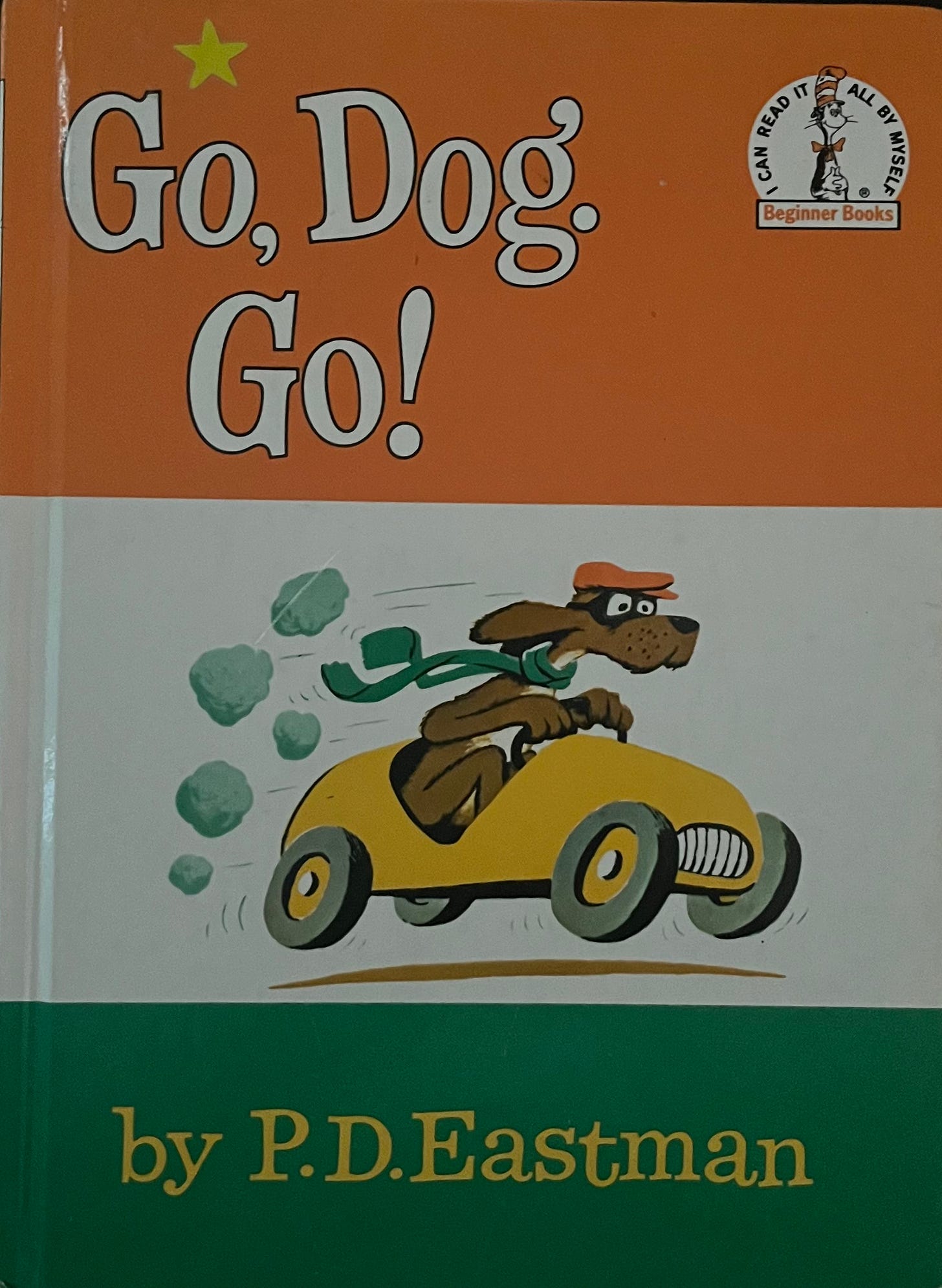

Across The Swamp Of Time . . . . “Outside the city limits there are many horrors,” declared Ignatius Reilly in A Confederacy of Dunces. The wisdom of Ignatius occurred to me as I was just a mile or two north of Atlanta’s city limits on an errand. Dunces abounded in a mid-afternoon traffic jam where no dogs and certainly no people ran free. Stuck on a six-lane road with the likes of Target, Burger King, Dunkin’ Donuts and other centers of fulfillment to the left and the right. Were those the places the people were headed to? Suddenly an image from P.D. Eastman’s classic children’s book, Go, Dog. Go!, came to mind. Toward the end of the book, there are hilarious illustrations of dogs driving their cars, pedal to the metal. The dogs looked happier than the people along North Druid Hills Road, however. And why not? They were headed to a Dog Party! The dogs drove to a gigantic tree. They slammed on the brakes, jumped out of their cars and climbed to the treetop. Up there among the clouds: the biggest canine party of all time.

The dogs had the better idea. They went to the party whereas the people in the fast food drive-thru emitted toxic fumes waiting for toxic burgers. If dogs run free, why can’t we; that sounds logical enough.

However, in 1970, Rolling Stone columnist Ralph J. Gleason felt imbued with a sense of new-found freedom. The release of Dylan’s New Morning album left him ecstatic. “We’ve Got Dylan Back Again!” was the headline of his November 26 Perspectives column. Gleason, a longtime champion of Miles Davis, believed just as much in Dylan. The much-maligned Self Portrait album, released only four months before New Morning, was only a bump in the road. And Gleason celebrated Dylan for “bringing it all back home again.” Gleason wrote:

This album is a sign. You believe that? I think I do. It is surely the best thing new to come over the airwaves and out of the grooves in I don’t know when and after those grim weeks of Agnew and Reagan and Nixon and Billy Graham and all that … , it was like the cool, clear water from a mountain spring to hear his voice so true, so good.

And though he regarded it as “simplistic,” Gleason lauded “If Dogs Run Free.”

“… If Dogs Run Free” with its jazz piano copping Avery Parrish’s solo on “After Hours,” the classic blues of the big band years. Kooper* has turned into a hell of a piano player. He’s got his chops up. He must have been working at that. And the vocal throw-back to Gloria Wood and Pete Condoli.

For something “simplistic,” “If Dogs Run Free” is filled with thoughtful elements. The scat-singing of the back-up vocalists, the late-night sound Kooper educed at the 88s, and Dylan’s pondering desires for the human species — desires not so irrational — that make one long for a less rapacious environment. It’s a world Dylan’s and P.D. Eastman’s dogs might conjure. But humans, like those at the Burger King, are running things. And when we fall, we fall hard, as was the case with Avery Parrish, the jazz pianist Gleason fondly remembered.

Only 22 years old when he played his classic solo on “After Hours,” with Erskine Hawkins’ Orchestra, Parrish seemed destined for a long and successful career. “The best is yet to come,” Parrish might have thought back in 1940. But acquisitive and ravenous notions get in the way, as do hot tempers, particularly when fueled by too much booze. That may have been the case in 1942 when Parrish was hurt badly in a bar fight. His injuries left him paralyzed and no longer able to play the piano. He lived 17 more years but had little involvement in music. In 1979, 20 years after his death, he was inducted into the Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. Sadly, his “what must be must be” wasn’t so unusual among those with two legs who think they’re running things. We’re all too human.

Then there are dogs in the real world, not in P.D. Eastman’s, who act as if they can handle things just as well as the men and women around them. For most of my life, there have been stories told about “Spot,” the dog my father and his brother had when growing up in the ’30s. They lived in East Point, a bedroom community just south of Atlanta. My grandfather had to hustle to find work in the Great Depression years, but he did better than some of his neighbors. At one time he worked at the Atlanta Federal Penitentiary, when they were playing host to Al Capone. Later on he worked in one of the departments in Atlanta’s Warner Brothers office. From what we gathered, Pappy felt more at home with Bugs Bunny than Al Capone. Perhaps it was the family dog, Spot, that inspired such a perspective. And maybe Spot picked up some things from Bugs Bunny.

According to Dad and other family members, Spot, a mixed breed (Cocker Spaniel and Newfoundland Water Dog), possessed human-like tendencies. 2 Legs Good, 4 Legs Just As Good was his motto. He’d roam the neighborhoods of the large but close-knit suburb. Spot always had a sense of where he wanted to go and how long he should stay there. Family legends reveal the truth. For example, one day the woman across the street from my grandparents’ house was waiting for her ride to work at the East Point Police Department. Her ride was with a police officer, in his black and white. The police car drove up. The woman got in, and from across the street, Spot ran and jumped in too. The woman told Spot to get out but the cop said the dog could come along for the ride. Spot was apparently familiar with the police station. Once at the station, Spot checked things out and was then told to go home. He did. Spot was used to the routine. Sometimes he’d end up at one of my great grandparents’ houses and make himself at home. Finally a call would be made to my grandmother, letting her know where Spot was. She’d ask to speak with Spot over the phone. “Spot, come home,” Birdell Cochran would say. He did. Dogs that run free also wish to please. As with P.D. Eastman’s dog, they’ll finally say they like your new hat. And with Spot, one phone call would do it all.

*Al Kooper