It Was the Year of The Beatles, It Was the Year of the Stones

Paul Simon explains 1964:

It was the year of the Beatles

It was the year of the Stones

A year after JFK

We were staying up all night

And giving the days away

And the music was flowing

Amazing

And blowing my way

Yes, The Beatles had conquered the world and they were only warming up. It’s early '64 and over the previous sixteen months, the band grew as studious and adventurous musicians, honing their performing chops. Possessing a solid work ethic, they developed a grounded, yet spontaneous sound in their studio recordings. Four guys in their early twenties working like old pros. Their two lead singers, John Lennon and Paul McCartney, were also gaining recognition as excellent songwriters. Within five years, they’d be considered right up there with the Gershwins as the best songwriting team of the 20th Century.

The Beatles had long coattails. As Paul Simon’s lyrics from “The Late Great Johnny Ace” acknowledge, following The Beatles from England and headed up the worldwide charts were The Rolling Stones. In the years ahead, Simon himself would contribute to the amazing stream of choruses enveloping our modern world. Creativity was spreading in the year after JFK and beyond.

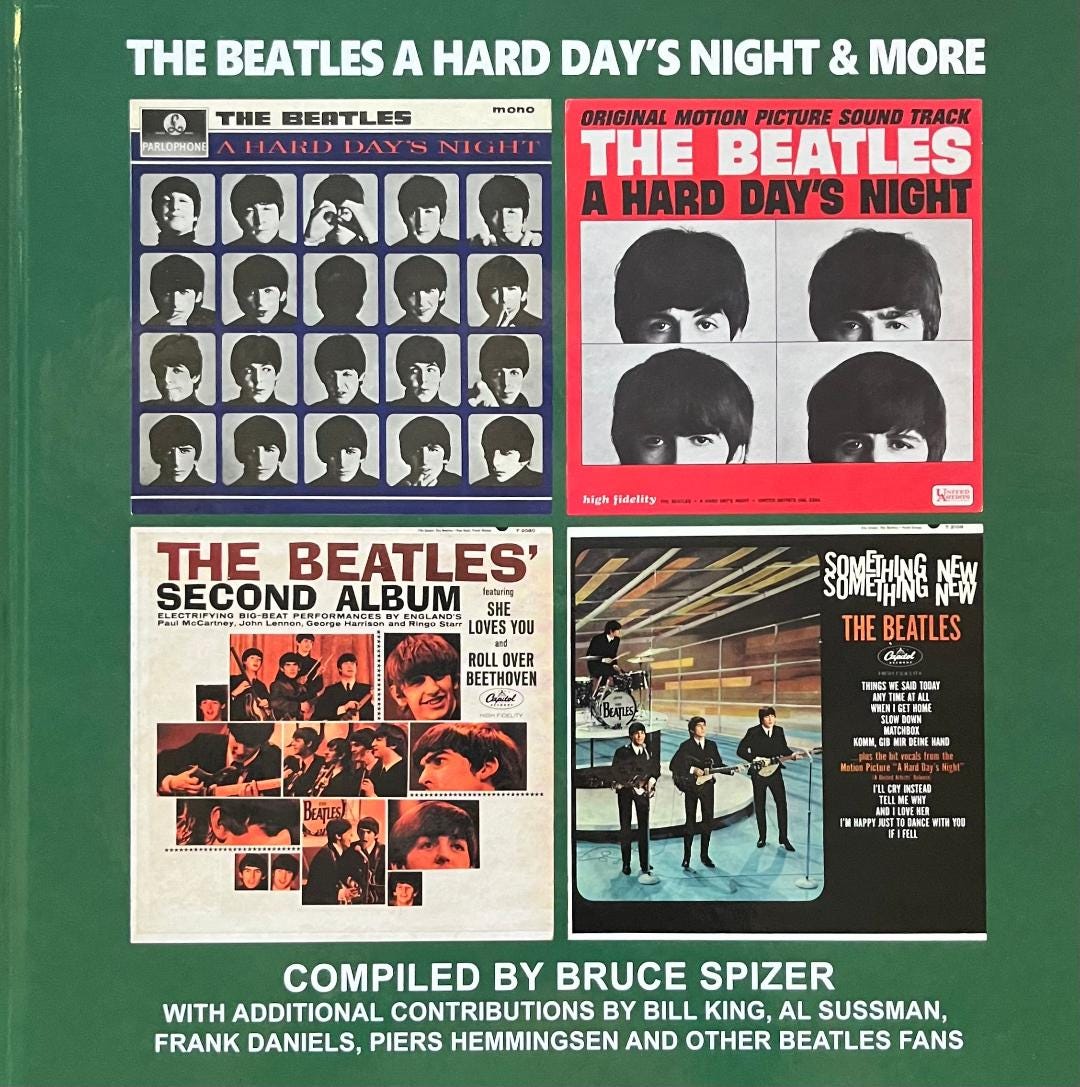

In The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night & More, another colorful and informative Beatles “album book” compiled by Bruce Spizer, readers are taken back to 1964. Major changes were taking place across the globe, but through the disruption and progress, what really had a hold on the world was The Beatles. Spizer and his contributors, particularly Al Sussman and Bill King, do a great job of reporting and reflecting on what excited and incited people — events and artistic expressions still having a major impact three generations later.

King, who grew up in Athens, Georgia, remembers reading the Atlanta newspapers as Beatlemania swept across America. Neither paper, The Atlanta Constitution nor The Atlanta Journal, was hardly enthusiastic while covering or commenting on The Beatles, although the afternoon Journal’s entertainment editor gave the film A Hard Day’s Night a favorable review. However, the us-versus-them attitude so obvious between the generations was manifested in the Journal’s Saturday TV section when letters from Beatles fans would run on the mailbag page, nearly each one compelling a disparaging remark about The Beatles by the paper’s TV columnist.

In the chapter, “The Music of 1964: The British Invasion & More,” Sussman refutes rock critics and “self-proclaimed historians” who regarded the rock and roll/pop music of “the period from '58-'59 until ‘I Want To Hold Your Hand’ … a musical wasteland, full of novelty songs, dance records and teen idols.” After all, by the end of '63, the Four Seasons and the Beach Boys brought new sounds to pop music. Then too, the Billboard Year-End Hot 100 Singles chart of '63 made clear the creativity coming America’s way was due to the emerging integration of Black people throughout the nation’s culture. A third of the singles on said chart were recorded by Black performers. Great names building careers and legacies: Ray Charles, Marvin Gaye, The Impressions, Stevie Wonder, Chuck Jackson, The Crystals, Barbara Lewis, Nat King Cole, Smokey Robinson and the Miracles. We could go on …

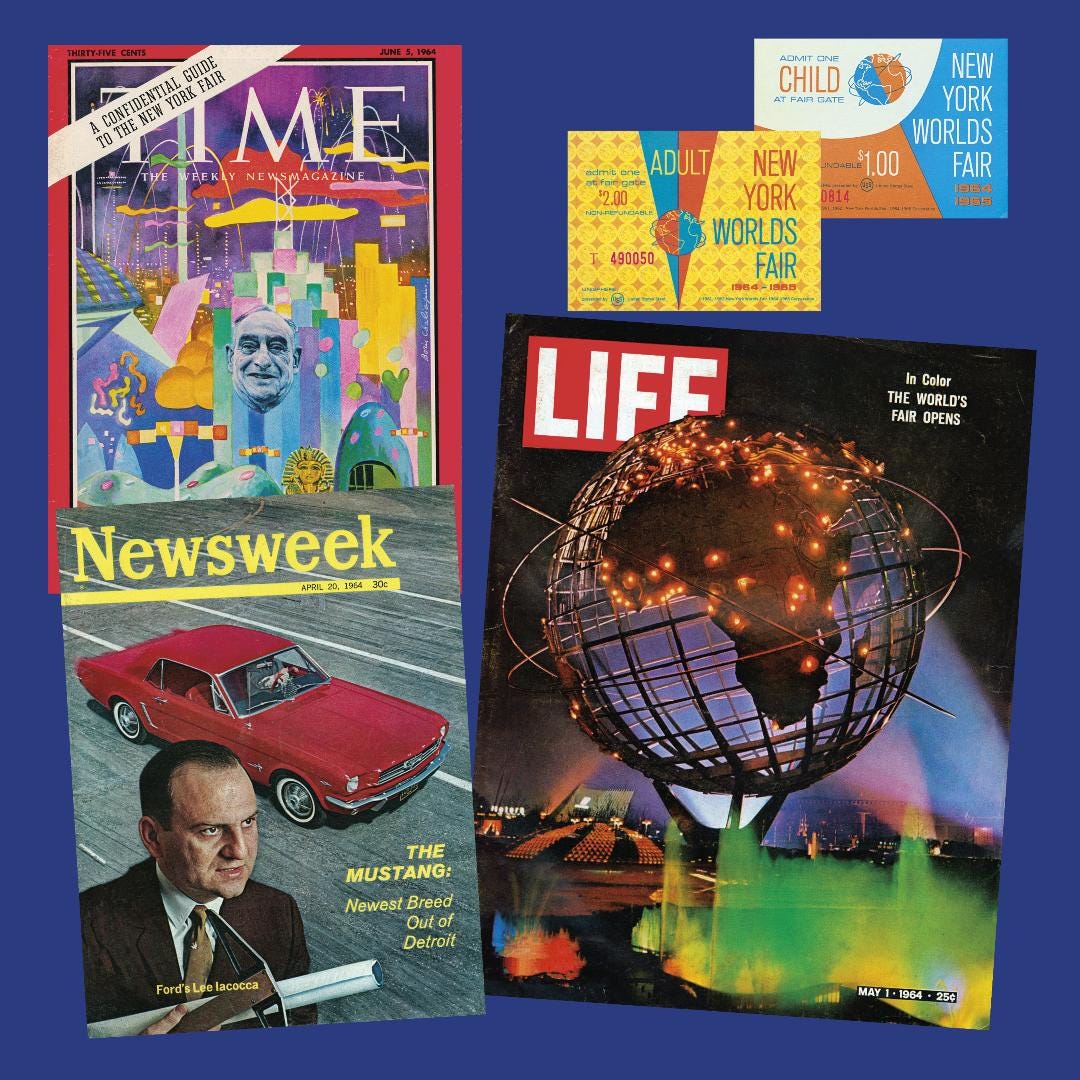

As in previous volumes of the Beatles album book series, Sussman also delivers a solid chapter on world events that conveyed progress, promise, and tragedy. In “the year after JFK” strides were made in granting all citizens of the United States the rights and freedoms our school teachers told us were all part of the natural order. But nothing worth having comes easy. Even with the euphoria that summer over President Lyndon Johnson signing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, there was still the influence of elected leaders such as Barry Goldwater, Strom Thurmond, and George Wallace making it apparent that the next goal, a strong voting rights bill, would be another huge challenge for the Johnson administration. Amazingly, the Voting Rights Act became law 13 months later, just as Johnson was digging a deep hole for himself and the nation in Vietnam. In this chapter, photos of covers from summer '64 Newsweek and Life magazines convey the possibility of an “ugly” and “widening” war in a country most Americans didn’t know existed. If your big brother was headed for combat, the family might bring out the globe and see exactly where he was being shipped. Determining why he and another 8.7 million Americans would serve there was more difficult than spinning a globe.

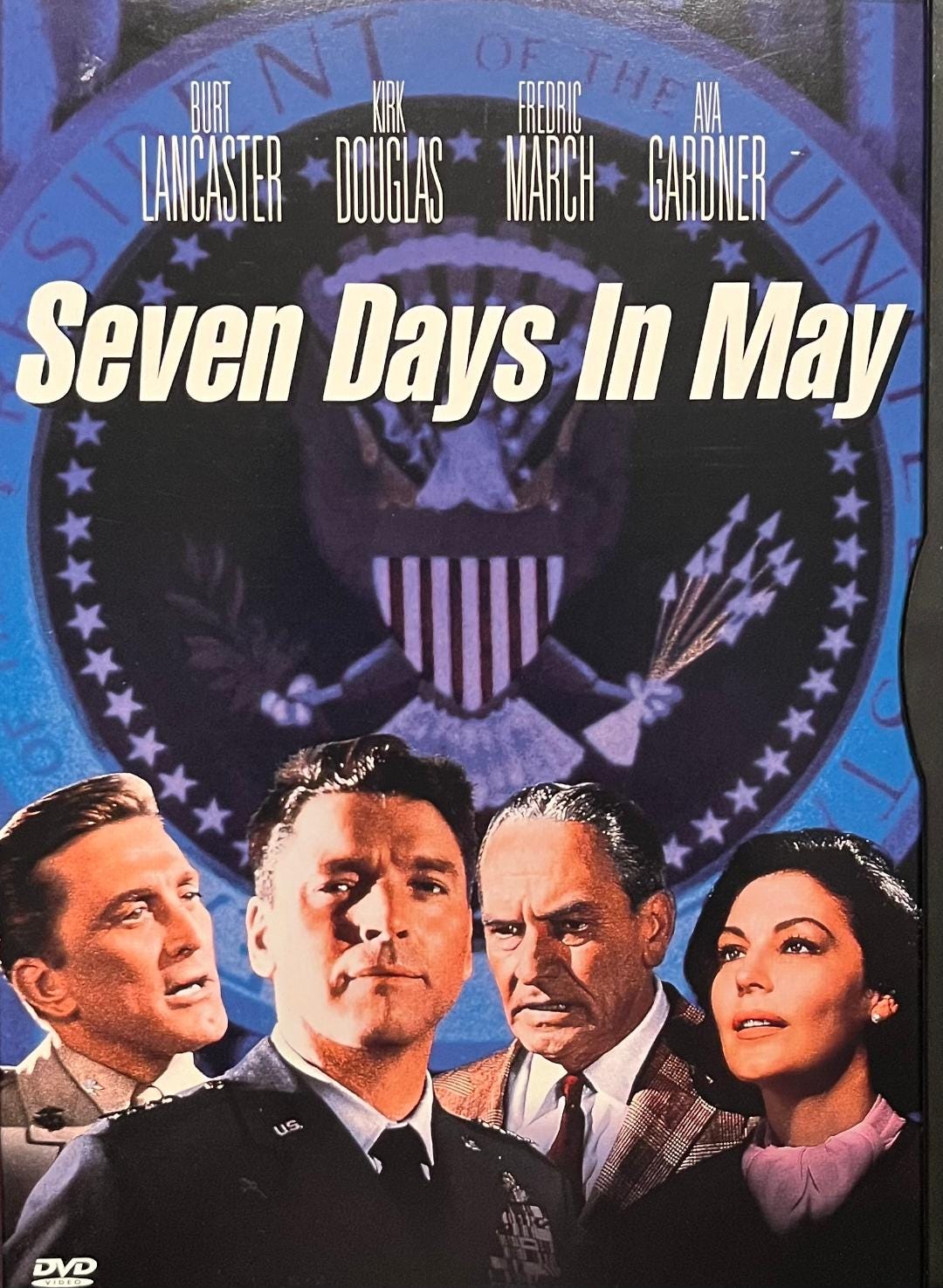

Frustrated with the political environment that mostly produced conflict, Americans sought respite at the movies. Spizer contributes an informative chapter on what the silver screen offered in '64 entitled “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Movies.” No doubt about it, there was enough escapist fare that was also smart entertainment to please millions of Americans who wanted to cast their worries aside, for a couple of hours anyway. On the big screens there were hits such as From Russia With Love, Goldfinger, A Shot in the Dark, Dr. Strangelove, Viva Las Vegas, and The Carpetbaggers. For the youngsters who would watch it again with their own kids 20 years later and with their grandchildren 20 years after that was Mary Poppins, the most popular film of the year. Of course, there was A Hard Day’s Night, a joyful, comic, and intelligent film starring popular music’s agents of change. In fact, change was evident throughout society and its consequences were particularly reflected in two films noted by Spizer: Seven Days in May and The Best Man.

Seven Days in May is a Cold War thriller that takes place several years in the future (purportedly 1970). President Jordan Lyman, played by Fredric March (he played Norman Maine in the 1937 A Star is Born), pushes for a nuclear disarmament treaty with the Soviet Union. The far-right Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General James Scott, played with every ounce of anger and resentment by Burt Lancaster, is not only opposed to the treaty, but seeks a military takeover of the government. Brilliantly working all the angles is USMC Colonel “Jiggs” Casey, who serves as Director of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (he answers to Scott). Portrayed by Kirk Douglas, Casey works with the president and Georgia’s US Senator Ray Clark (played by another great one, Edmund O’Brien) to thwart the planned coup. They are successful. The four Joint Chiefs are out and Lyman tells the nation that America builds its strength through peace and not by conflict.

A cast of March, Lancaster, Douglas, and O’Brien, joined by Ava Gardner and Martin Balsam, with an intense screenplay by Rod Serling, should have guaranteed long lines at the cinemas, but that didn’t happen. Surprisingly, O’Brien was the only one of the film’s cast who received an Academy Award nomination.*

Sussman, in his Changin’ Times, November 22, 1963 — March 1, 1964 101 Days That Shaped A Generation, published in 2013, delves deeply into Seven Days in May and reveals some backstory intrigue regarding its plot and how President John F. Kennedy supported the making of the film. The president had read the novel the film was based on and having dealt with Cold War era military chiefs himself, found the possibility of a military coup quite believable. Not the least bit surprising was that the Pentagon opposed the making of the film.

The Best Man, with a screenplay by Gore Vidal, was another topical film with a great cast that generated little drawing power, perhaps only matching the box office receipts of Roustabout, the least popular of the three Elvis Presley films in '64. The Roustabout cast includes Barbara Stanwyck, Leif Erickson, and film noir heavy Steve Brodie, but is weighed down by a hackneyed plot and a dull soundtrack. The Best Man. however, features Henry Fonda, Cliff Robertson, Edie Adams, Ann Sothern, Shelly Berman, and Lee Tracy. And they all get to say plenty.

Fonda stars as William Russell, the likely Democratic nominee for the '64 presidential race. The Republicans aren’t a factor in the film, not even mentioned (how great that would be this year), but there are other Democrats contending for the nomination who are acting and talking like Republicans, especially when it comes to equal treatment of Black people. Among them is a firebrand senator, Joe Cantwell, based on Senator Joe McCarthy. As with the shamed commie-baiting senator from Wisconsin, there are no depths too low for Cantwell to stoop (yet another reminder of what we’re dealing with this year) if it puts him in power.

Cliff Robertson’s portrayal of Cantwell is right up there with his “Tolly Devlin” in Samuel Fuller’s Underworld. Cantwell is the type of politician America can never seem to get enough of — or shake off. He’s a populist who wants to keep the country alarmed, ready for war, be it overseas or at home, particularly when the government oversteps its bounds in guaranteeing Black Americans equality at the lunch counter, the voting booth, and the workplace. There’s a great scene during a Democratic Party dinner with Cantwell bopping his head and clapping his hands along to the great Mahalia Jackson singing “Down by the Riverside.” Jackson declares she “ain’t gonna study war no more.” What a dichotomy Cantwell is; he’s bopping in that chair, grooving to the Black woman’s song, as she does exactly what Cantwell believes she was born to do: Entertain the white folks, even as she’s singing about dashing war from her mind while war of one kind or another is all Cantwell thinks about.

Robertson’s Cantwell is the telegenic demagogue, the type we’d come to see more of in the years to come. In his rare calm moments, Cantwell’s almost Kennedyesque, which makes sense given that JFK requested Robertson play him in the film, PT 109, released six months before Kennedy was assassinated. Robertson’s JFK is cool, calm, and heroic, trying to find some humor in the art of staying alive.

1964 also gave us the World’s Fair in New York and the Ford Mustang, but the year kicked off with the Surgeon General’s announcement regarding the link between cigarette smoking and lung cancer. Amazingly enough, the legitimacy of that link would be debated for decades. (It wasn’t until 1988 that the phasing-in of smoking bans on commercial airlines began.)

On February 10, less than a month after the Surgeon General’s report, Columbia Records released Bob Dylan’s The Times They Are a-Changin’. The title song has maintained its relevance in the 60 years since and will continue to do so. Dylan’s proclamation to writers, critics, parents, politicians — and pretty much all of us — revealed what had already changed, what still needed to change and that changes along a new road would lead to a better destination. The name of the song itself has found its way into various stories explaining changes experienced or changes at hand, even in less weighty matters like professional sports, as 1964 was also the year the upstart St. Louis Cardinals defeated the New York Yankees in the World Series. Talk about times a-changin’. After that, through 1975, the Yankees would not appear in a World Series, a startling change in America’s pastime, given that the Yankees had only missed the World Series twice between ‘49 and ‘64.

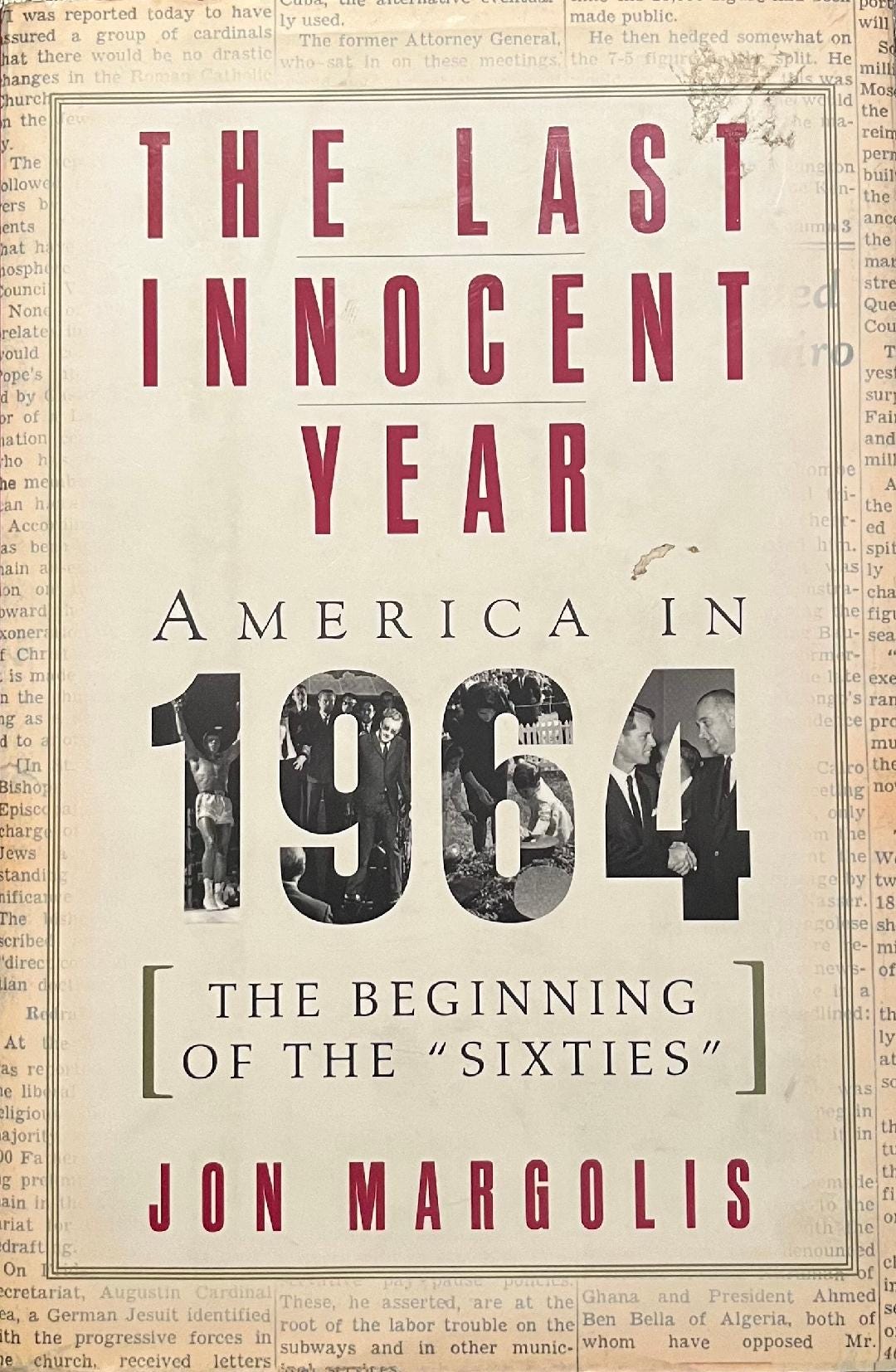

In 1999, The Last Innocent Year, a book about America in 1964 by journalist Jon Margolis, was published to high acclaim. Margolis covered much of the same ground as Spizer and Sussman have in their volumes, but his assessment that America was in the process of losing its innocence that year is hardly a universal conclusion. In fact, it’s just wrong. Ask the Cherokee Indians who walked the “Trail of Tears” when America lost its innocence. Or ask Harriet Tubman. Or the victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921. A list of those who’d question whether America ever possessed innocence would be quite lengthy. But in regards to The Beatles, Margolis correctly declared that young Americans were shaking loose long-held norms and embracing a sense of rebellion. For American parents, it was enough that their teenagers were loudly playing “I Want To Hold Your Hand,” “I Saw Her Standing There” “She Loves You” and other Beatles songs throughout the day, but it seemed a collapse in decorum had taken place. Margolis noted the dissension in households far and wide:

It got even worse when American boys started trying to look like the Beatles. The barber business suffered throughout much of the country as teenage boys began to let their hair grow, the better to look like John, Paul, George, or Ringo. Family harmony suffered too. In thousands of living rooms, kitchens, and dens, parents pleaded, urged, cajoled, bribed, and finally commanded their sons to get a haircut.

Margolis gathered the fifteen-year-olds had no choice; they “did as they were told or else.” But seeds of rebellion had been planted. In the years ahead, there’d be more to disagree about with parents, teachers, pastors, and coaches than hair length. For those who embraced the music and spirit of The Beatles, a sense of rebellion came naturally when noting how life could flow in a more positive direction with an easing of authority, or simply enough, a breakdown of the my-way-or-the-highway attitude. That rebellion wouldn’t lead to vengeance or animus, but instead to a greater sense of independence, even to that great sense of elation called joy.

No, 1964 was not the last year of innocence; it was the year of The Beatles. Just ask Paul Simon. Ask anyone who was paying attention then. Ask someone like Bruce Spizer, whose The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night and More reveals many of the reasons why.

First, and foremost: The music. One week after their third Ed Sullivan Show appearance aired on February 23, The Beatles were back in England, at work on their third album, A Hard Day’s Night, which would include 14 songs, all written by Lennon and McCartney. The album’s title cut, also the title song to The Beatles’ first full-length feature film, opens with a major declaration. It’s that chord, one that’s both startling and welcoming. The greatest show on earth had stepped up its act. And what else did they have? Plenty.

A Hard Day’s Night, the UK version, is one of the four albums featured in the latest of Spizer’s “album book” series, and it’s not only the best of the four, it’s widely considered to be the best of The Beatles’ first five UK albums and perhaps equal to Rubber Soul, their sixth album. The other three albums covered are two US releases on Capitol, The Beatles Second Album and Something New, and the official soundtrack album to the film, A Hard Day’s Night, released in the US by United Artists (the film’s distributor).

Just earlier this year, A Hard Day’s Night, the UK version, was highly praised in The Guardian. Reviewer Colin Fleming called it “a euphonic album of joy … a primer on joy like A Christmas Carol, The Wizard of Oz, The Wind in the Willows, and It’s A Wonderful Life.” In his review, Fleming grew even more effusive, describing the album as “salve and inspiration,” adding:

Its propulsive electro-power could animate Frankenstein’s monster: the bridge of the title track, the falsetto backing vocals of “Tell Me Why,” the solar plexus punch — in a good way — of that guitar solo in “Can’t Buy Me Love” that in turn makes you want to punch the air and shout your head off.

Fleming was equally impressed with one of the album’s gentler songs, “If I Fell,” explaining why we knew, even back then, that we were dealing with uniquely different songwriters in John Lennon and Paul McCartney:

“If I Fell,” the album’s third track, looks to be a love song, with tender harmonies. But listen closer. A person has been hurt. They want assurances that they won’t be again. They’re frightened. Conflicted. And yet they are alive in that very conflict, in the push-and-pull of losing and loving. They’re becoming aware of this as they go along. This is joy.

Spizer, as in previous volumes, sheds light on how The Beatles’ albums were configured in the US by Capitol versus what have long been considered the official album releases, those on EMI’s Parlophone label in the UK. The process was convoluted, often insulting towards The Beatles, but now and then, it resulted in great packages, especially with The Beatles’ Second Album. The title was delusive, as it was actually The Beatles’ second album on Capitol, but what the label rendered was The Beatles’ best pure rock ‘n’ roll album. Kicking off with “Roll Over Beethoven” and closing with “She Loves You,” they never let up; the sequencing was red-hot.

With the exception of “Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand (“I Want to Hold Your Hand,” sung in German), Something New revealed The Beatles raising and clearing the bar once again. Included were five songs recorded for the film, A Hard Day’s Night, plus four other Lennon-McCartney originals and sizzling covers of Larry Williams’ “Slow Down” and Carl Perkins’ “Matchbox.” Missing, due to Capitol’s negligence or tacit agreements with United Artists, were “I Should Have Known Better,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” and “A Hard Day’s Night,” perhaps the three best songs from the film. Instead, “Komm, Gib Mir Deine Hand” makes it as the closing cut, an inclusion Spizer said “was not only something new, it was something weird.”

That “something weird” was the exception that proved the rule, however. In 1964, and in the years ahead, we learned to not only expect something new, but something highly original and brilliant from The Beatles. In his latest Beatles book, Bruce Spizer also meets expectations, providing thorough and concise coverage on great music with colorful and intriguing backstories.

*O’Brien did win a Golden Globe award for Best Supporting Actor.

**Presley’s other two films in ‘64 were Kissin’ Cousins and Viva Las Vegas.

(1964 New York World Fair and Ford Mustang illustrations from A Hard Day’s Night and More.)