James Brown’s Legacy: Papa's Mixed Bag

James Brown may have been telling more than he intended on his 1974 hit, “Papa Don’t Take No Mess.”

Papa didn’t cuss

He didn’t raise a whole lotta fuss

But when we did wrong

Papa beat the hell out of us

Papa was calm but Papa could explode. And so it was with James Brown.

The man’s smile could light the way on a starless night. His music inspired and enthused. James Brown couldn’t make the lame walk but he could make the rhythmically-challenged learn to groove.

Yet James Brown had that downside. A Rolling Stone cover story by Michael Goldberg in April '89 revealed how Brown beat the hell out of those dear to him. Like wives. And girlfriends, including the singer Tammi Terrell, who became involved with Brown when she was 17. Bobby Bennett, a member of Brown’s back-up vocal group, the Famous Flames, told Goldberg that Brown “beat Tammi Terrell terrible … she was bleeding, shedding blood, she left him because she didn’t want her butt whipped.” Another former Flame, Bobby Byrd and his wife, Vicki Anderson, described to Goldberg how Brown in the ‘70s, abused his wife at the time, Deirdre, “something terrible.”

All the women liked his money and his fame,” says Anderson. “They liked being Mrs. James Brown. This is nothing new. The minute he buys you the first thing — next will come those beatings.”

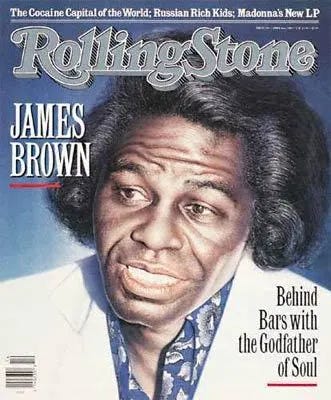

(May 9, 1989 Rolling Stone, featuring James Brown story by Michael Goldberg. Cover illustration by Gottfried Helnwein)

Goldberg’s story appeared when Brown was behind bars in South Carolina for carrying an unlicensed pistol, assaulting a police officer, and a heaping handful of drug and driving offenses along I-20 near the South Carolina-Georgia border. Incarcerated, Brown could do little to shut down the horror stories about his character and his often violent way of doing business. Goldberg described the Brown emerging as “not so regal,” and “a man who’s been wrestled to the ground by a host of personal demons.”

In his Brown biography, The One, R. J. Smith offers some highlights from Brown’s drug-fueled marriage to his third wife, Adrienne Lois Rodriguez, both flying on PCP:

Many addicts have described how the drug makes time seem to speed up, and make hours and days seem to flutter in an instant. For James and Adrienne, at any rate, events were rocketing forward, and the drugs created a whole new kind of rhythm in their lives, oscillating between crazy rage and operatic displays of affection.

She called 911 to report domestic violence in 1984.

Three times in 1985.

Once in 1987.

At least seven times in 1988.

Adrienne filed for divorce in ‘88, but she and James reconciled. That didn’t mean things were good. On Halloween night ‘95, James beat Adrienne again. According to Women’s e news, Kay Mixon, a battered women’s advocate in South Carolina, met Adrienne in the emergency room. “She was all beat up,” said Mixon, who urged Adrienne to seek refuge at a shelter, but to no avail, accepting only Mixon’s offer of a ride home. Adrienne did file charges against her husband, but died* on January 6, 1996, making the charges null and void.

In 2004, there were charges filed against Brown for allegedly pushing Tomi Rae Brown, his fourth wife, at their Beech Island, South Carolina home. Mixon, convinced Brown was a wife batterer, understood the patterns, telling Women’s e news, “I wasn’t surprised, I knew it was coming.”

A lot of people, those with personal knowledge of the demons preying on Brown, as well as those in the business who would hear things, were just like Kay Mixon — not surprised by the revelations of his malevolent personal life. His unspeakably rotten behavior had been going on for decades. Yet the preeminent purveyor of “Showtime” knew, whether at a packed arena or having a personal conversation with an important politician, that he had to play the James Brown his adoring public had long embraced. Soul Brother Number One wouldn’t let them down. And their memories of his dynamism often overwhelm the reality of the pain he caused.

That dynamism came across at the Peaches Records and Tapes in Atlanta late in the summer of ‘76. As many other great artists had, Brown arrived at the store one afternoon to place his hands in cement, à la Grauman’s Chinese Theatre, alongside the Peachtree Road sidewalk of our store. Brown was very gracious, treating all those he met as lifelong friends. Some artists treated such appearances as something-they-had-to-do. Brown approached it as something-he-really wanted-to-do. In less than two years, the store had hosted greats such as The Allman Brothers Band, Dolly Parton, Roger Daltrey, The Isley Brothers, Boz Scaggs, and Willie Nelson for the cement events. Those of us working there could get a bit jaded about our A-list visitors, but we were usually excited to be part of the appearances, especially with someone like Brown who brought his own special brand of excitement. Lee Berman, the store director, who relocated from our store in Hollywood, was all smiles, hardly believing he was getting paid to be there. “Meeting him was one of the most fantastic things I was ever part of,” said Berman, who doesn’t have an unkind bone in his body and who I observed to always be respectful of all our employees. As with many of us back in the mid ‘70s, he would have been startled over Brown’s treatment of women.

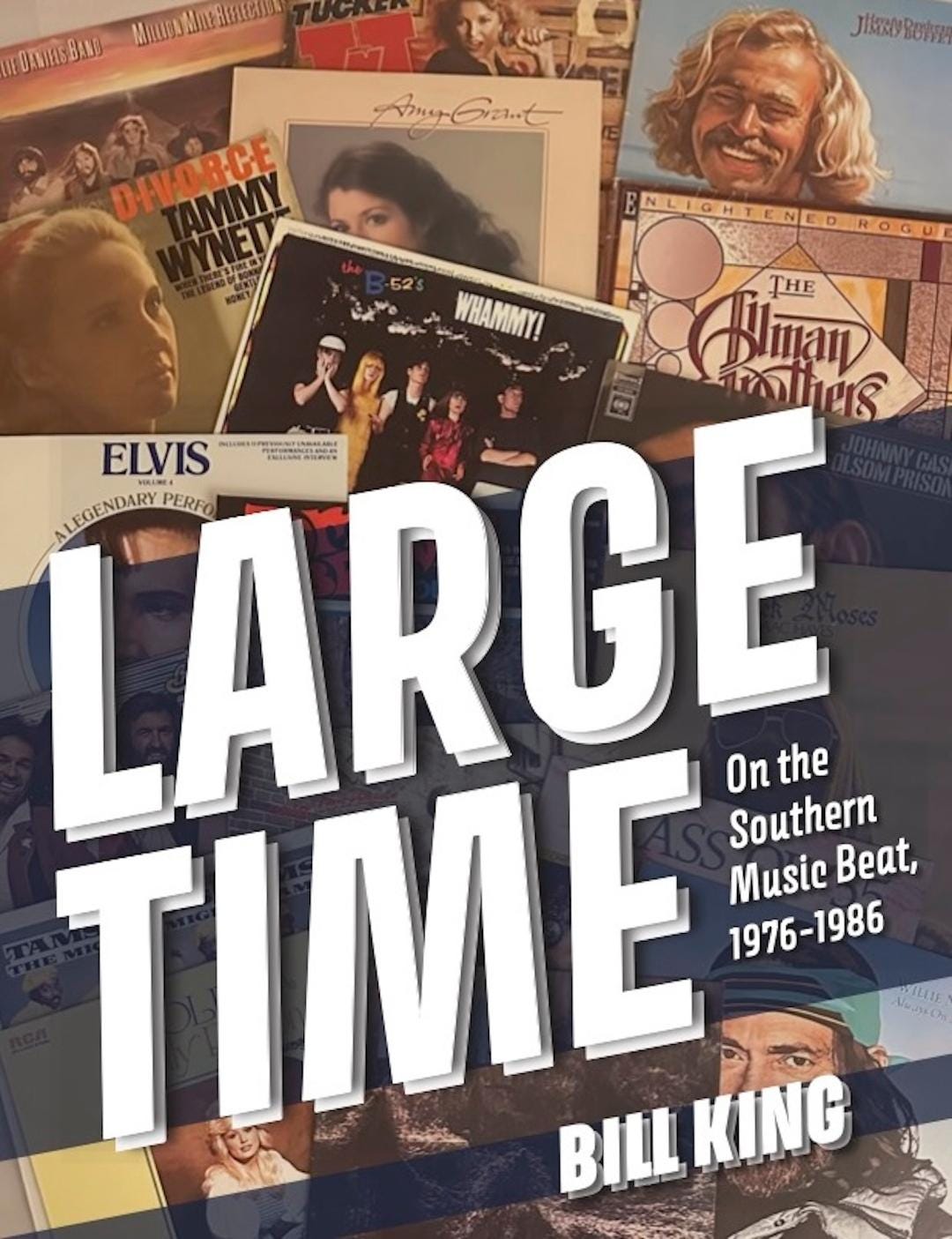

In Large Time, his excellent book on the Southern music beat, 1976-1986, Bill King devotes a chapter to the day in 1980 that he spent with James Brown in his hometown of Augusta, Georgia. Brown was his usual ebullient self, serving up plates of fried chicken for lunch, driving King around town in his Mercedes while making several stops around town. They drove to meet an old school teacher of Brown’s, then to the billiards hall, where King was introduced to the man Brown was endorsing in the Augusta mayor’s race. On the final errand, they visited a car customizing shop where a Winnebago Brown bought was being outfitted. Then it was back to Brown’s office, where King met Al Sharpton, who until recently had been Brown’s tour manager, but several years from becoming a national political figure. A pretty full day. King was getting quite a story for The Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

Having made a splash in the recently released film, The Blues Brothers, Brown was basking in the glow of another of his comebacks. The Godfather of Soul was not wanting for self-confidence, telling King, “I know I’m a model man,” dismissing those who questioned his motivations. He was just warming up, “Every minute of the day I’m doing something for humanity. You hear a lot of stories about me because I try to be a hard driver on the surface. But, in here,” he said, patting his chest above his heart, “ain’t nothin’ but bubblegum.”

Brown mentioning “a lot of those stories about me” may have been his way of acknowledging while also dismissing reports of his being a hard-assed and vindictive bandleader. It was 1980 after all, still at least a decade and a half before the internet was widely relied upon as a conveyor and storage unit of information. An article in a magazine with scant circulation focusing on Brown’s mistreatment of band members could get some attention at first but quickly lose steam. Brown could delude himself and others with his “model man” talk, realizing few were aware of the demons working inside him. Besides, he came off as genuine, an out-of-the-ordinary guy in all the right ways. When chatting recently with Bill King about getting that story on Brown, he told me he was “thoroughly charmed by him while being fully aware I was the recipient of a daylong PR blitz.” And some performers do their work better than others, especially when any time can be “Showtime.”

In 1996, Atlanta hosted the Summer Olympic Games. The athletes and media from around the globe were joined by some of the world’s most famous entertainers. A House of Blues (HOB) was set up in the old Baptist Tabernacle building downtown, near the newly constructed Centennial Olympic Park. For those who cared more for music than athletic competition, HOB was the happening place. In about two weeks’ time, Dr. John, Bobby Blue Bland, Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Al Green would be among the top names booked. Bob Dylan would close out the series of shows on August 3 and 4. Dylan’s 8/3 set wowed the audience, especially with his blazing rendition of the Grateful Dead’s “Alabama Getaway,” one of the night’s encores.

Still, there could be no “Showtime” in Atlanta without James Brown. So on Friday night, July 26, James Brown took the stage in the tented area at HOB. According to reports, he was uneasy about performing in the old Baptist church building. It was the sacred-versus-the profane dilemma. There’d be more reasons to feel uneasy later on.

But before he took the stage, all was right with James Brown and the Atlanta Olympics. On the site Humid City, a writer who worked for HOB remembered seeing Brown arrive for his show:

He pulled up in a Snow White stretch limo with a vanity plate that said “Godfather.” He hopped out fizzing with energy, and immediately started shaking hands and kissing girls at the security perimeter. Yes, he really seems like that all the time.

Hours later a bomb went off in Centennial Park. It was 1:19 a.m., Saturday. Terrorist Eric Rudolph had come to town.

Not everyone in the vicinity knew what happened, but the HOB crew was on top of things. The Humid City writer describes the events surrounding James Brown:

When the pipe bomb went off, my friend Vaughn and I had to tell (Brown) there would be no encore.

The Godfather was not happy:

What do you mean there will be no encore? I’m the Godfather. These people want to see the Godfather and I’m not going to disappoint them.”

They told him a bomb had just gone off at Centennial Park, hardly a block away. The Godfather of Soul had a sudden change of heart:

“Where’s my limo? Where my women at? Let’s get out of here.”

James Brown was a tough guy but he was no fool. Besides, he had more than ten years left in him. There were a lot more shows to give. People wanted to see the Godfather and he didn’t want to disappoint them. That confidence and dedication are admirable, but his “Where my women at?” comes off most badly when we keep his personal history in mind. Those women - “my women” - in his show that night in Downtown Atlanta: Were they pushed, kicked, and slugged all for the privilege of getting to perform with the hardest working man in show business?

*Ms. Brown died due to complications from cosmetic surgery.

Interested in reading more about Bill King’s afternoon with James Brown? King’s book, Large Time is now available. Directions are as follows:

You can get a copy for $39.99 postpaid in the U.S. or $69.99 postpaid outside the U.S. Add $10 to the cost if you’d like a numbered, signed copy! Send a check, money order or credit card information to: The Goody Press Books, 3009 Delcourt Drive, Decatur, GA 30033. You also can pay via PayPal to goodypress@gmail.com, or via credit card at 404-713-6432. Address all inquiries to goodypress@gmail.com. For an order form or to read more about the book, go to https://beatlefan.com/book-store.