Jimmy Carter Walks the Talk and the Slow Train Comes Around the Bend

Sometimes I feel so low-down and disgusted

Can’t help but wonder what’s happening to my companions

”Slow Train” by Bob Dylan, 1979

Throughout his life in politics, business, and as a leader in his church, Jimmy Carter has no doubt wondered what was happening with his companions.

Let’s go back to 1958. Carter was little more than a third through his life, but he was already an accomplished man, staying busy, visualizing, creating, and expanding on ideas to make the world a better place: There in the southwest corner of Georgia he called home — and beyond. Getting his point across often meant butting heads with his companions. At times, even leading up to his election as governor of Georgia in ‘70, he compromised on values that were key to who he was. He’d look the other way or make deals with people who were not companions. Those deals and compromises can’t be sources of pride, but Carter hung in there. He’d keep at it and work at making the world a better place. That’s how legacies are created.

Arguably the greatest living American, Jimmy Carter is due to celebrate his 100th birthday this October 1st and even though he’s no longer at work, his visions continue to move ahead on their own momentum. After all, Carter not only shared his visions, he made plans. If our nation is fortunate and gives thought to future generations, then people in Southwest Georgia and around the globe will celebrate Carter’s 200th birthday on October 1, 2124. Hopefully, the fear that grips America now will ease off as his vision continues to be shared. But back in 1958, he wasn’t celebrated or even appreciated beyond a small group of companions. No one was talking legacy then.

Carter, a deacon and Sunday school teacher at Plains Baptist Church, found himself at odds with his companions when it came to Black children and white children attending the same schools in Sumter County, where by 1850, white citizens owned as many as 4,000 slaves. Just prior to the Civil War, more than half of the county’s residents were enslaved. Through the war, Reconstruction, Jim Crow, and legalized segregation, Blacks had to worry over just how cruel life would be in Sumter County and elsewhere in the South. Anyone advocating change had his work cut out for him.

Carter served on the Sumter County Board of Education and found that even making the most minute steps toward integration in the southwestern Georgia county were considered radical moves, inspired by communists. For Richard Balmer’s 2014 biography, Redeemer, Carter recalled there were only a half dozen families in his hometown of Plains who were “moderates” on the racial issue at the time of Brown v. Board of Education. Several of them, Carter said, “were run out of town.” He knew better than to count on help from his companions.

The acrimony and enmity toward Blacks in Deep South communities like Sumter County could even alter the direction a good man like Jimmy Carter would take in order to help Black citizens. The fury of those fomenting hatred intimidated — or surely quieted — those advocating a simple we’re-all-God’s-children approach to the racial divide. The bigots’ scare tactics made decent citizens worry over their homes, their livelihoods, and even their lives. It became most easy to grow blind to what was really happening right in front of them. It made Carter’s work all the more difficult. His companions didn’t want to be run out of town. And Carter would eventually want his companions to send him to a higher office. He wasn’t ready to go toe-to-toe with his companions. So, he didn’t do as much for his Black friends as he knew he should. The memory of that would trouble his conscience for decades to come.

In one of his memoirs, Turning Point, published in ‘92, Carter recalls visits to the white schools of Sumter County, and then its Black schools, seeing for himself what he should have known many years before. He described the folly of the “separate but equal” policy the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education ruled against in ‘54:

There were two high schools and three grammar schools for white students, and it was natural that we visit them first. We found them to be in fairly good condition, although the buildings were pre-1930s vintage. Buses served all the rural homes, books were adequate and current, and there were numerous extracurricular activities in sports, drama, extemporaneous writing, and debating.

Then we began visiting the county schools for black children. There were twenty-six of them for the elementary grades, a few of which also served high school students. There were so many sites because no buses were provided, and schools had to be within walking distances of the children’s homes. The books were those that had been declared too worn out for use in the white schools. Classes were held in various places, including Sunday school classes of black churches and even private homes. For some reason, my most vivid memory is of large teenage boys trying to sit on chairs designed for children of kindergarten age. After a few of these embarrassing visits, my fellow board members and I found reasons not to go on any others.

Rosalyn Carter, in her memoir, First Lady From Plains, wrote of similar discoveries at the Black schools in Sumter County:

Their typewriters and textbooks were old, discards from the white schools.

Mrs. Carter also voiced frustration over how friends and loved ones couldn’t get past segregation:

Though we were both raised in the South and had accepted segregation as children, Jimmy and I had traveled enough to see a different way of life. In the Navy, Jimmy had lived and worked on an equal basis with blacks and could not go home and support the same old status quo. The racial issue had always been a sore subject with Jimmy and his father, who believed that segregation was best for everyone.”

Jimmy’s father, known as Mr. Earl, was adamant about his position. Whenever a Black teenager, who Jimmy’s mother, Miss Lillian, had encouraged to go to college, came by to see her, he’d walk up to the front door. Not out back, as tradition required. Mr. Earl wouldn’t grant the kid the simple dignity of greeting him. Instead he’d duck out the back way or just sit in his room rather than acknowledge the young man’s presence. Mrs. Carter explained that such attitudes were deeply engrained in the South “and they would not easily go away.”

Living up to what his faith in Christ taught him wasn’t always easy for Carter. Like many of us living in the Deep South in the mid-20th century, Carter found his companions didn’t want to obey the law, even as made clear by the U.S. Supreme Court. They’d even try to prove water runs uphill, as in claiming the Black schools were equal to those white children attended. By ‘60, Carter was chair of the Sumter County School Board, working to help Black children while trying to placate racist whites. In Redeemer, Balmer observes the futility of such efforts:

Carter sought to improve black schools in the district, part of a strategy employed throughout the South to avoid integration by ensuring that facilities were more nearly equal, albeit separate. Carter himself acknowledged that “the ‘separate’ was the only part honored in the South,’” however, and that there “was certainly no equality between Black and white students.”

In Turning Point, Carter goes on to describe the political landscape of Georgia when it came to the matter of educating all of the state’s children. He points to Georgia’s senior U.S. Senator, Richard Russell, who served in the Senate from 1933 until his death in 1971, as being “the undisputed leader of the segregationist forces” and notes that, on eleven occasions, beginning in ‘38, he used “his immense prestige, power, and political wiles” to thwart federal civil rights legislation. There was also Governor Ernest Vandiver, who won election in ‘58 by promising to keep Georgia public schools segregated. In a campaign speech, he declared, “When I am your governor, neither my three children, nor any child of yours, will ever attend a racially mixed school in the state of Georgia. No, not one.”

Talk about a campaign hook deep in the Jesus-haunted buckle-of-the-Bible Belt. “No, Not One!” was a beloved hymn in Protestant churches across the land. Whether part of a worship service with just a dozen or hundreds, congregations sang it with gusto, or as the instructions in some hymnals suggested, “Slow, and with great feeling.” The exclamation point in the title conveys boundless desire for the friendship, love, and humility offered by the “lowly Jesus.” Johnson Oatman, a New Jersey Methodist-Episcopal minister, wrote the lyrics to “No, Not One!” in the mid 1890s. It was just one of the popular hymns in which Oatman wrote the lyrics; among the others were “Higher Ground” and “Count Your Blessings.” Sadly, the title of his song extolling the “lowly Jesus” was misappropriated by segregationists to insure that Black citizens remain lowly in the public square.

Not even in church, where many of Carter’s companions sang of the friendship they had with the “lowly Jesus,” could hearts and minds be changed. Never mind education, the ballot, or access to various professions, whites in Sumter County, as elsewhere in the South, wouldn’t even open their church services to Black people. In the chorus of “No, Not One!” are the words “Jesus knows all about our struggles. He will guide till the day is done.” Did conservative white Christians believe Jesus was concerned about the struggles of the Black people among them? It didn’t seem like it.

In his political ascendency, Carter needed the support of conservative white Christians, but as much as he wanted their votes, he also wanted to change hearts and minds in Southwest Georgia. Quite obviously, that would be no easy task, as he learned up front and personal in the summer of ‘65. Carter, by then a State Senator, had to rush back from a wedding north of Atlanta for a congregational meeting at Plains Baptist Church. Members would be voting the next day on the Board of Deacons’ resolution barring Blacks from entering the church. The resolution was hammered out the week before, when, conveniently enough, Carter was speaking at another church. Back in Plains and before the congregation, Carter spoke on the resolution, urging they vote against it. Joining Carter in opposition to the resolution were Rosalyn, two of their children, his mother, and an elderly member who may not have understood the issue. Fifty members voted in favor, with a majority of those in attendance abstaining. In First Lady from Plains, Rosalyn looked at the cloud and found a silver lining, albeit a thin one:

When we got home, the telephone was ringing. Many of the church members told Jimmy they agreed with him but couldn’t face the consequences of voting publicly to integrate the services. And many of our boys’ friends told them they also believed the church was wrong but were afraid of their parents’ displeasure. This is the first indication we had that a majority of our people felt as we did and were ready to end the long struggle against integration. Nevertheless, the resolution to keep blacks out of the church was passed, and it was an experience our boys have never forgotten. Or forgiven.

Whenever Jimmy Carter walked his talk, he and his family realized it could hurt their business at the peanut warehouse and cost him votes in the political races ahead. If he was going to change the spirit and direction of government, the reason he ran for office in the first place, he first had to win votes. So, he would often obscure his liberal beliefs on race. Or he’d even encourage voters to associate him with popular segregationists. During his short-lived congressional campaign in ‘66, Carter called himself “a Dick Russell Democrat.” Russell, a legendary and learned politician, served nearly forty years as a U.S. Senator from Georgia. While not as racist as other southern politicos such as Strom Thurmond and Theodore Bilbo, Russell still endeared himself to Georgia segregationists by standing in opposition to “political and social equality with the Negro.” When President Harry Truman began to voice support of civil rights for Black Americans, Russell declared it “an uncalled-for attack on our Southern civilization.” That “civilization” was what Carter wished to change. His efforts in getting a chance to do so weren’t always pretty.

A statue of Georgia U.S. Senator Richard Russell, on the grounds of the state capitol in Atlanta, Georgia. Russell is one of several racists memorialized on the capitol grounds.

Ten years after Carter’s truncated bid for a Georgia congressional seat and his unsuccessful first bid for the governor’s office, he was elected President of the United States and inaugurated on January 20, 1977. Carter won a razor-thin victory over the incumbent Gerald Ford with the enthusiastic support of Black Americans. Longtime civil rights workers, legendary figures among them, led the way for Carter. He would take many of them along to Washington where they could work together on improving civilization.

Less than two years into Carter’s term in office, his friend Bob Dylan converted to the Christian faith. Like Carter, Dylan was more than happy to talk about Jesus and would even go so far as to make Him the subject of most of the new songs he would release in the next 2-3 years. Agree with him or not, it would be difficult not to hear Dylan’s take on the Word.

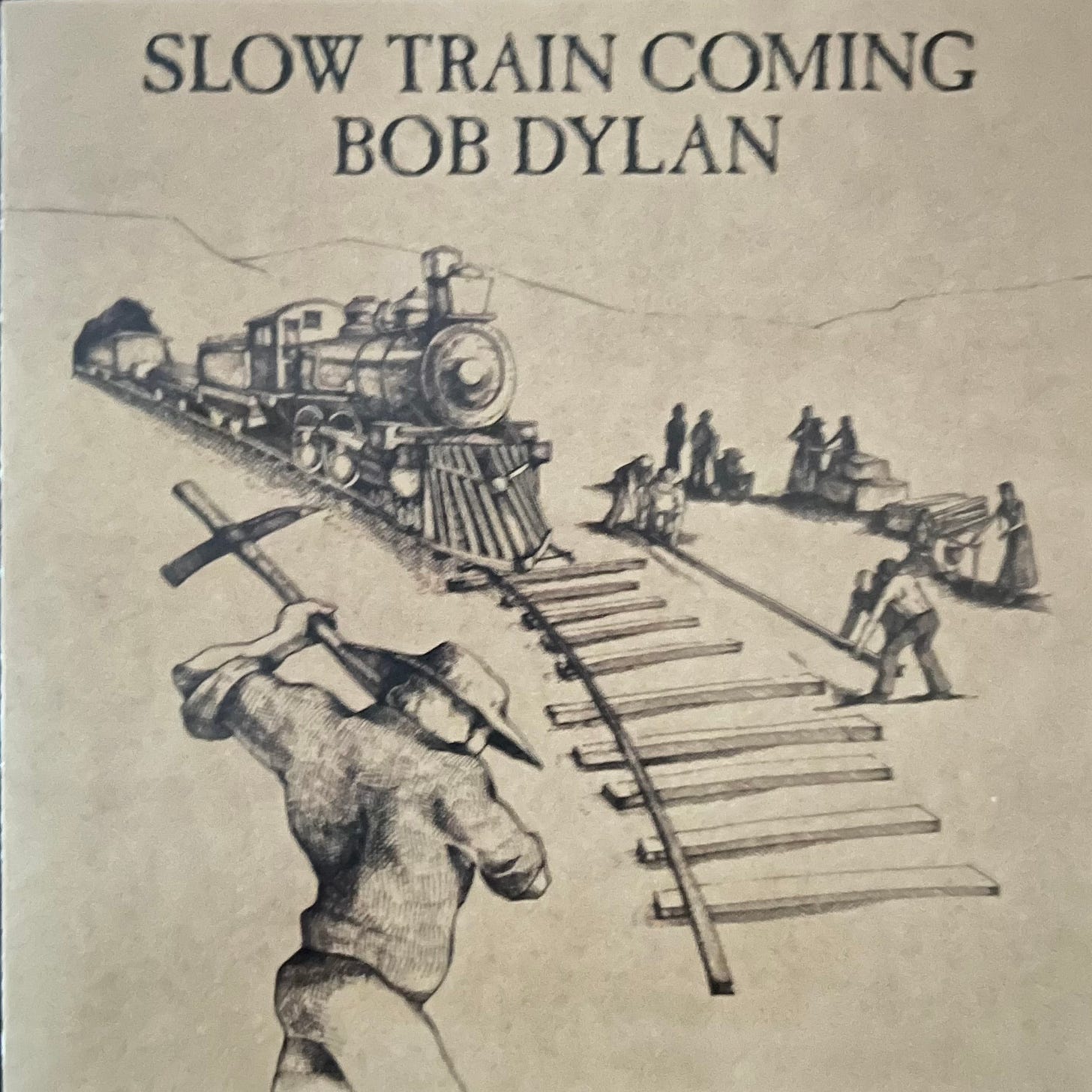

“Slow Train,” nor any of the other songs on Bob Dylan’s album, Slow Train Coming, were included in any Southern Baptist hymnals after its release in ‘79, but the album was embraced by Christians of every stripe. Here was the great bard of rock and roll not only proclaiming the divinity of Christ, but also clarifying how Christians should live — how they should be strong in the faith. At times, Dylan’s messages came off as too fundamentalist for Christians more open to various interpretations of the scriptures, while the more conservative Christians happily exalted a rock-and-roller now singing straight from the Bible, never mind that in his 17-years of recording, he had used biblical imagery and passages from the Bible at least 122 times.

Unlike the other songs on Slow Train Coming, “Slow Train” is not evangelical in its presentation. Dylan scholar Clinton Heylin has called it “an Old Testament rant, but very much in the modern-day protest singer’s vernacular.” Still, at least six times the song features lines referenced from the New Testament, with two being the words of Christ. But then again, it is like a modern-day protest song, as Heylin noted.

In 1979, a modern-day protest singer couldn’t help but enumerate grievances. It was an unhappy time in the United States. No matter how much Jimmy Carter worked to make the government “as good and decent and competent and compassionate and as filled with love as are the American people,” trouble would find America. A fiasco in the works in Iran, which Carter once declared an island of stability. Double-digit inflation. The price of a barrel of oil doubling in just one year. Fearing an oil shortage like that in ‘73, motorists lined up at the gas pumps in a spate of panic-buying. In some instances, drivers waited more than a hour for gas, with lines stretching a half mile. At a Los Angeles gas station, a motorist assaulted a pregnant woman he claimed cut in front of him. Fisticuffs at the pump were commonplace. Carter invited leaders across the country to Camp David for discussions on restoring the nation’s sense of community. That was a tall order for a country short on ideas. The American people were filled with anger and frustration as opposed to compassion and love.

Jimmy Carter wasn’t inclined to tell his fellow Americans that “Sometimes I feel so low-down and disgusted” as Dylan did in the opening line of “Slow Train,” but of course he felt that way. Carter was too smart to feel otherwise. He wondered how to deal with an Ayatollah, angry Americans, and companions who called themselves Christians, but pushing a strain of the faith he didn’t recognize. The “slow train comin’ up around the bend” felt like judgment upon us all.

Another chapter on Jimmy Carter and Dylan’s “Slow Train” will appear the week of September 16 on this Substack page.