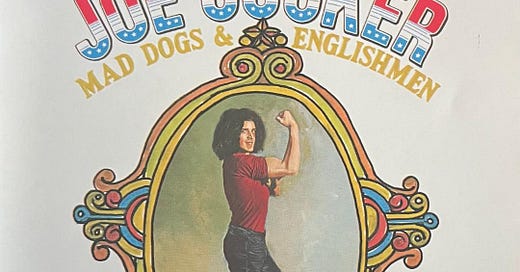

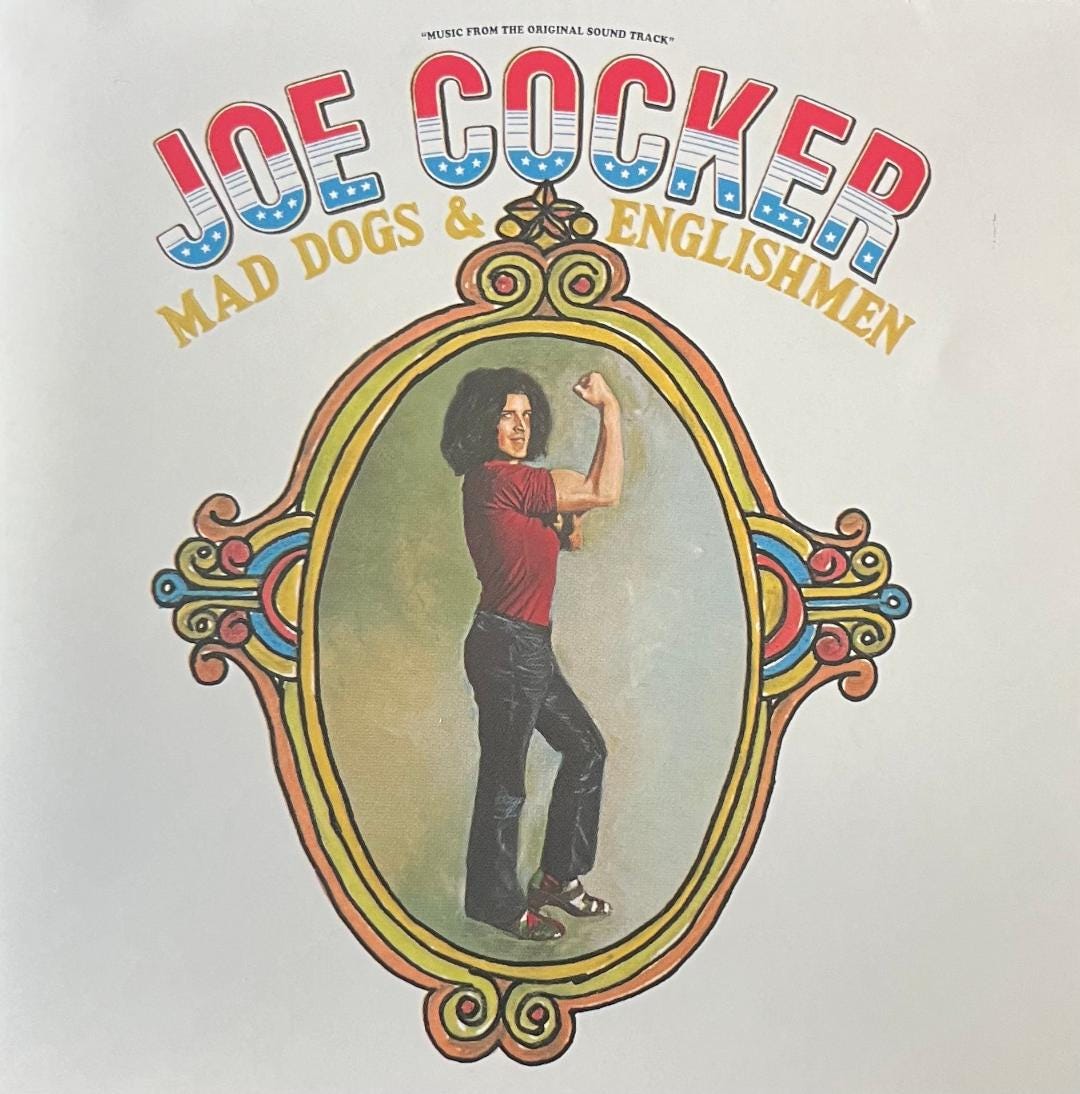

Decades before his passing, which occurred on December 22, 2014, the obit for Joe Cocker was likely being held in readiness at newspapers and periodicals throughout Europe and America. The reportage by 1972, even in Rolling Stone, gave readers the impression that Cocker was trashing his career while on the way to becoming rock’s next drug casualty. This was only three years after his triumphant appearance at Woodstock. Only two years after his electrifying Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour — and its subsequent concert film and soundtrack. The soundtrack album featured Cocker’s two latest hit singles, his other-worldly takes on “The Letter” and “Cry Me A River.”

“The Letter,” a breakout hit for the Box Tops in summer '67, gets a serious upgrade on Cocker’s version. Joe is at his full-throated best, ecstatically moaning; his lonely days are gone and he’s goin’ home. The big band treatment, coming in fast and hard, soars and the back-up singers are mesmerizing as they chant/sing, “My baby wrote me a letter/My baby wrote me a letter/My baby wrote me a letter….” When performed live, it seemed Cocker and his troop could levitate the Fillmore East. Cocker didn’t need a ticket for an aeroplane. He could make it back to his baby on his own power.

Cocker’s rendition of “Cry Me A River” is as distant from Julie London’s '56 hit version as Key Largo, Florida is from Neah Bay, Washington. Arthur Hamilton, the song’s composer, still with us at 98, wrote the song in ’53 for a film, Pete Kelly’s Blues, directed by Jack Webb. (Yes, that Jack Webb.) Perhaps Hamilton’s friends regarded Cocker’s “Cry Me A River” as chaotic, but it was magnificently-arranged chaos, with Cocker’s big band, led by Leon Russell, playing even more intensely than they did on “The Letter.” Whereas London’s fetching vocal performance is sultry and pouty, Cocker’s is aggressive; he creates a straight-ahead rocker that leaves little doubt of the protagonist’s anger. Released as a single in September '70, Cocker’s “Cry Me A River” peaked at #11 on the Billboard Hot 100. It wasn’t the only fiery single to climb the charts at the time. “War,” by Edwin Starr peaked at #1 on September 11, 1970.

The early '70s was a time of great innovation in rock and roll, but for a brief period, Cocker stood alone. He took the songs you knew by heart: standards from rock, rhythm and blues, and pop — even going as far back as the prohibition era with “Bye Bye Blackbird” — and made them his songs. The Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Leonard Cohen and even Ray Henderson, still around to hear a new twist on the '20s classic he wrote with Mort Dixon, had to be impressed with Cocker’s singular interpretations of their songs. Rock critic Robert Christgau, never free with praise, wrote that Cocker was “rock’s best interpreter.” For Joe Cocker, the only direction was up. Or so it seemed.

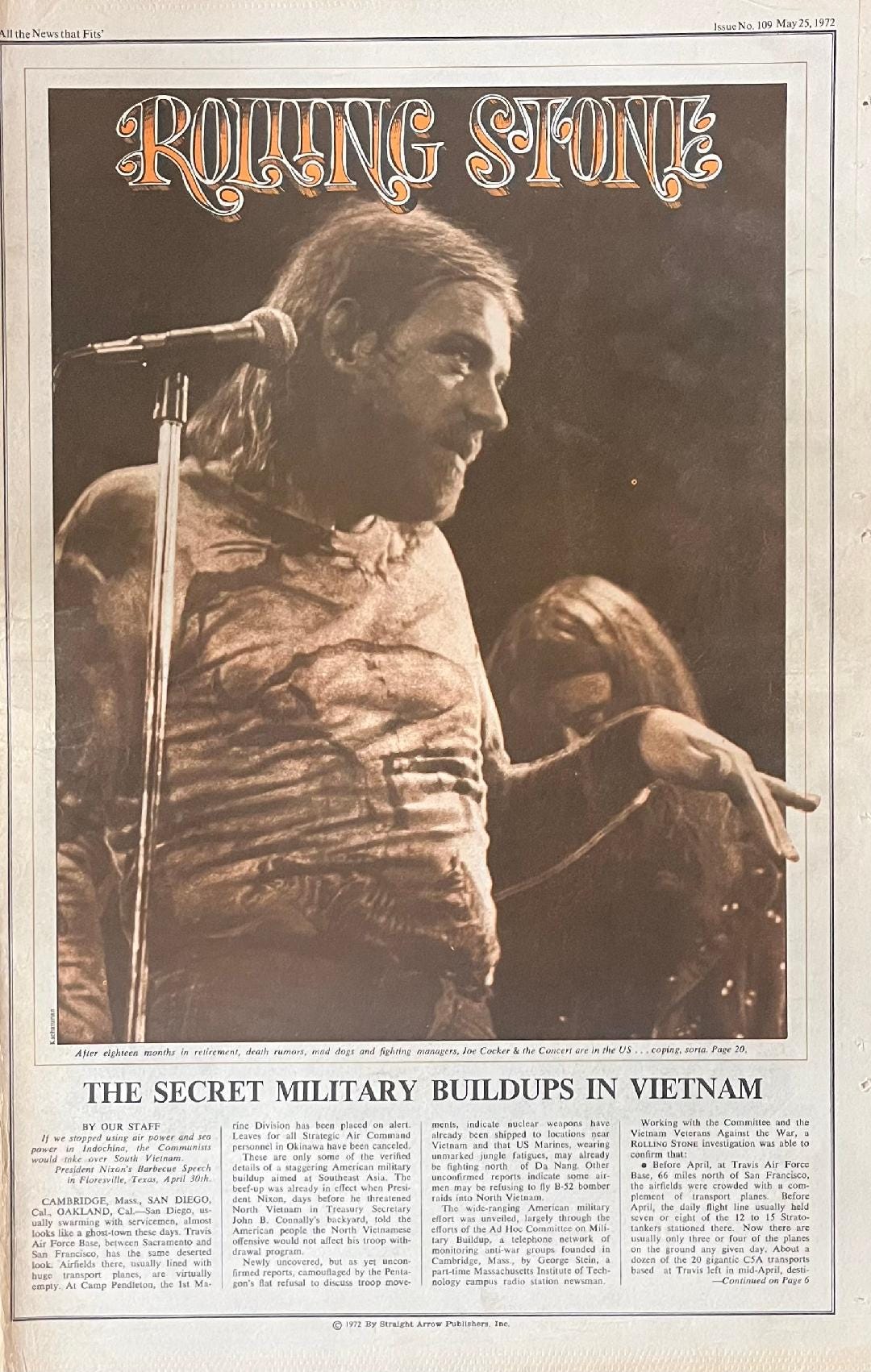

Cocker had management issues. As with many artists, he likely had more dollars coming than he actually received. And as with many performers living on the road, he felt a sense of boredom that could only be vanquished by alcohol and drugs. Or so it’s said. In the May 25, 1972 Rolling Stone, Timothy Crouse wrote of catching up with Cocker the night before a big show at Madison Square Garden. The opening night of his tour. In New York City. Crouse observes that Cocker didn’t have his mind on the show:

Joe was drawing long deep tokes on his joint. Just one of those tokes would have sent any opera singer reeling, terrified, for the throat spray. But Joe kept on inhaling and holding his breath, and he showed no sign of remembering that his vocal chords were the band’s single most valuable asset.

After the Madison Square Garden opening, Joe would say, “I was very hoarse at the Garden. We’d been rehearsing up to the day, which I’d forgotten about.” On the eve of the opening night, he seemed to be trying very hard to forget. Cocker’s girlfriend explained it all to Crouse, “You know, on the road, you need the booze and the drugs and what-not just to cope with all the creeps that push themselves on you.”

She had a point about all the creeps. An artist is targeted by managers managing to manage — for themselves. There are leeches pitching this and that, knowing a performer can be an easy touch. So Cocker commenced to “cope.” Crouse again caught up with Joe later on the tour, this time in Boston. The New York show was a stinker, but the performances had been picking up some since the tour opener. In a hotel room before the Boston concert, Crouse witnessed Joe getting another sort of pick-me-up.

Joe puts down his joint, poured out a neat pile of coke from a plastic pill bottle on the bed table, and took a deep snort. “Oh my, it’s fine! he crowed, “Wakes you right up.”

A curious aspect of Crouse’s story, entitled What’s Going On Here, Joe Cocker? was the judgmental tone regarding drug use in — of all places — Rolling Stone. In those days, the partaking of illicit stimulants wasn’t often criticized in the magazine, which had among its subscribers a fair amount of druggies. But Crouse, author of The Boys on the Bus, sensed Cocker’s career was going down fast. His article explained why.

As a follow-up to the success of the Mad Dogs and Englishmen soundtrack, in November ’72 Cocker released a self-titled collection of live recordings and studio tracks, which mostly tasted of leftovers. There were a couple of Cocker rave-ups, however. One was his rendition of the Allman Brothers Band’s “Midnight Rider;” the other, “High Time We Went,” a hit from the year before. With an unrelenting push by pianist Chris Stainton, “High Time We Went” is a barn-burner that doesn’t let up. Cocker gave it his all in the song — hardly a serious composition, just a groove that he and Stainton put down and drove hard, like a long, intense jam. Cocker and Stainton performed as if their lives depended on it. Just as we expected of Joe Cocker in those days. But expectations can lead to disappointments.

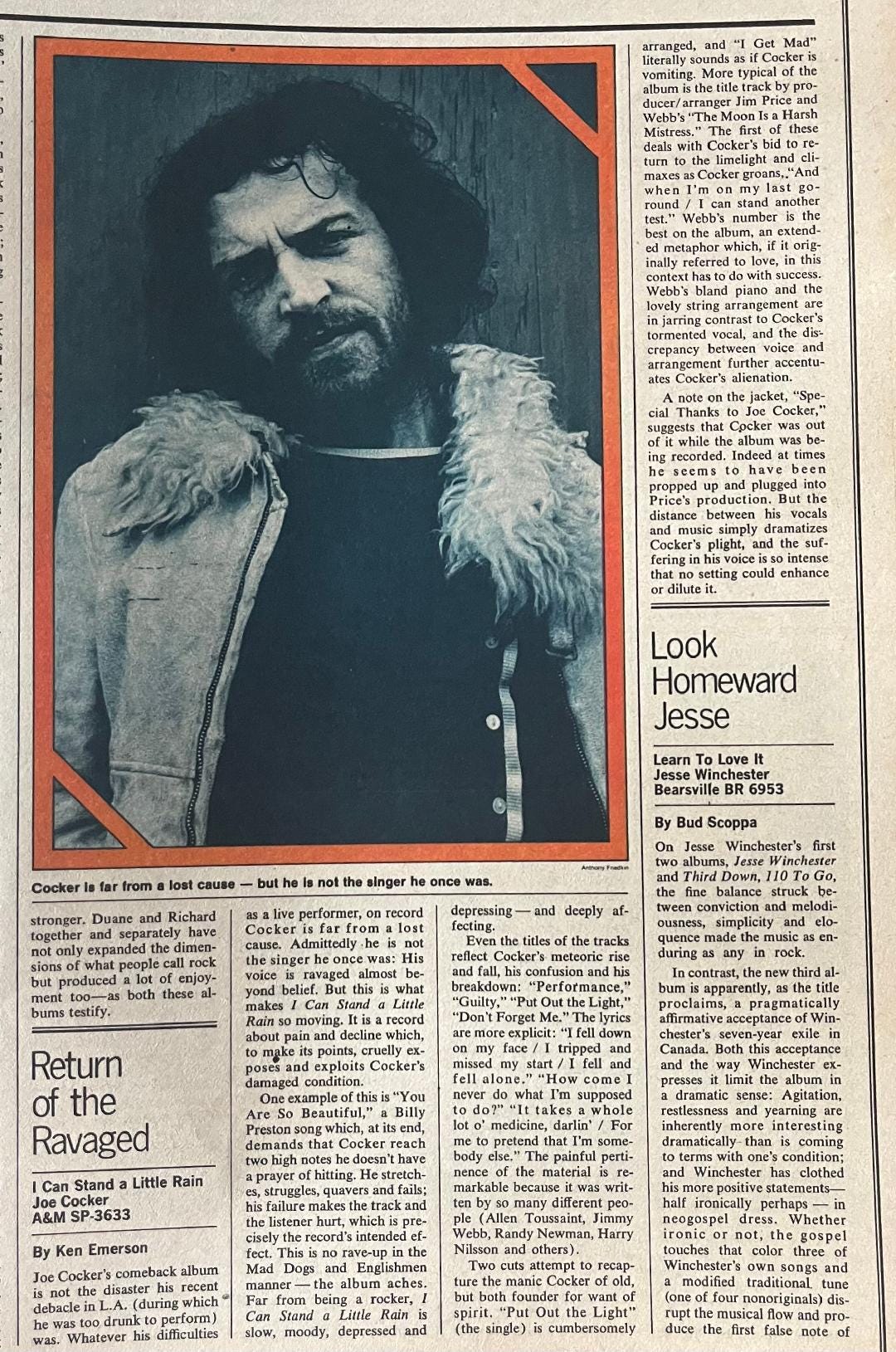

Again Rolling Stone, this time in Ken Emerson’s review of Cocker’s ’74 album, I Can Stand A Little Rain, shed light on the singer’s impasse. Given the title of the review, Return of the Ravaged, Emerson sure didn’t sugarcoat it and he was spot-on with his perspective:

His voice is ravaged almost beyond belief — but this is what makes I Can Stand A Little Rain so moving. It is a record about pain and decline, which to make its point, cruelly exposes and exploits Cocker’s damaged condition.

One example of this is “You Are So Beautiful,” a Billy Preston song which, at its end, demands that Cocker reach two high notes he doesn’t have a prayer of hitting. He stretches, struggles, quavers and fails; his failure makes the track and the listener hurt, which is precisely the record’s intended effect.

Yes, “You Are So Beautiful” was painful for many listeners, but masochists throughout America pushed the single all the way to #5 on the Billboard Hot 100. Cocker’s pain was his gain, softening the blows from Emerson’s review, which also said that one cut, “I Get Mad,” “literally sounds as if Cocker is vomiting.” Emerson was most prescient. During the same month his Cocker review was on the newsstands, Cocker allegedly threw up during performances in Seattle and San Francisco. Those sad incidents would shape the image Cocker would deal with in the years to come, especially once John Belushi’s uncanny impressions were seen by millions. Here was a great artist hitting bottom. The acclaimed singer who once commanded the stage was considered a laughing stock. Still, Cocker’s achievements of just a few years earlier would always matter; the great recordings still resonated. No doubt, that compelled Emerson, with his tough but honest review, to strike a thoughtful tone when called for:

Even the titles of the tracks reflect Cocker’s meteoric rise and fall, “Performance,” “Guilty,” “Put Out The Light,” “Don’t Forget Me.” The lyrics are more explicit: “I fell down on my face/ I tripped and I missed my start/ I fell and I fell alone.” “How come I never do what I’m supposed to do?” “It takes a whole lot o’ medicine, darlin’/ For me to pretend I’m somebody else.” The painful pertinence of the material is remarkable because it was written by so many different people (Allen Toussaint, Jimmy Webb, Harry Nilsson and others).

Emerson’s review is accompanied by a photo of Cocker, with the caption, “Cocker is far from a lost cause — but he is not the singer he once was.” That, however, was not as bleak as how Emerson closed the review:

But the distance between his vocals and music simply dramatizes Cocker’s plight, and the suffering in his voice is so intense that no setting could enhance or dilute it.

Singing was Cocker’s job; he didn’t think himself a lost cause and wasn’t ready to throw in the towel. Like a young pitcher who lost his fastball and attempts to reinvent his style and motion, even if it meant a trip to the minors, Cocker hung in there. Those who knew there was no way Cocker could summon the power he did with Mad Dogs and Englishmen hoped he could at least come up with a “High Time We Went” on occasion. As it was, such hope was soon abandoned.

Word got out that Cocker had recorded “Catfish,” Bob Dylan’s song about New York Yankees pitching great Jim “Catfish’ Hunter.” What seemed promising enough was a letdown. The low-key recording by Dylan* captured the essence of a “lazy stadium night” and imagery of what was then America’s national pastime. But Cocker swings and misses at the fastball right in his wheelhouse. His “Catfish” has no atmosphere nor does it convey the sly humor Dylan intended. It could be that Cocker didn’t know Catfish Hunter from Peggy Fleming. The album featuring “Catfish,” Stingray, was no hit either, peaking at #70 on the US charts upon its release in spring ’76, just as Hunter was beginning what would be his last great year on the mound, displaying the endurance Joe Cocker or even Mick Jagger would envy.

But again, Cocker hung in there. His personal life improved as he continued to record albums featuring songs by the likes of Dylan, Jimmy Cliff, and Randy Newman. Parke Puterbaugh of Rolling Stone, reviewing Cocker’s ’82 album, Sheffield Steel, was encouraged that Cocker was showing some of the spirit of 10-12 years back, even if the fire didn’t run as hot. It was “rockin’ chair rocking,” said Puterbaugh. Sheffield Steel peaked at 105 on the American album charts. Cocker’s old fans gave him little thought at the time. Just a distant memory, like the brown acid and skinny-dippin’ at Woodstock.

A few months after Sheffield Steel was released and quickly forgotten, Cocker hit pay dirt for the first time in more than a decade. Yielding to the gentle persuasion of producer Stewart Levine, Cocker, along with Jennifer Warnes, recorded the soppy “Up Where We Belong,” which was featured in a soppy moment of the film, An Officer And A Gentleman. “Up Where We Belong” wasn’t anything he would have played with Leon Russell and the boys at the Fillmore, but it was a huge hit. It soared to #1 on the pop charts, winning a Grammy and an Academy Award for best song. The song was omnipresent in the early Reagan years, just like Ed Meese, Debra Winger and the TV show, Family Ties.

All one can hope was that Cocker made lots of money from the song. At one time he owed A & M Records, the label he made big money for, as much as $800,000.00. Given the ubiquity of “Up Where We Belong,” Cocker may have had a good bit left after settling his debt.

For the rest of his life, Joe Cocker, his vocal fire burning much lower, became sort of an adult-contemporary pop singer. His CDs shared space on shelves with Michael McDonald, Neil Diamond and the poster boy of fallen rockers, Rod Stewart. Aesthetically, that left lots to be desired but Cocker was just glad to be among the living. Like the steel industry in his native Sheffield, South Yorkshire, England, Cocker’s dominance was a thing of the past, but he would improvise and find new pursuits. To his credit, Cocker embraced life beyond the stage. He and his wife, Pam, married for 27 years, settled in at their Mad Dog Ranch in Crawford, Colorado. There Cocker was well known for contributions to the community through the Cocker Kids’ Foundation. The kids in Crawford and throughout the North Fork Valley in Delta County have long needed a little help from their friends. According to the 2000 census, the average household income for families in Crawford was $27,500.00 with 29.4% of the population below the poverty line.

Established in 1998 and until it closed in 2019, the Cocker Kids’ Foundation succeeded due to close involvement by its namesakes and board members. According to its website, Joe and Pam Cocker “made sure that the funds have impacted the kids who need it the most.” Since its founding, the Cocker Kids’ Foundation funded over $1,000,000.00 to programs and grants aiding area youth under 21 in achieving their goals in the fields of education, recreation, arts and athletics. The Cocker Kids’ Foundation also honored school teachers in the region.

This generosity of spirit and deed calls to mind a chance meeting with Cocker in the late ’70s. He was in Atlanta for a concert. The promo guy from Elektra-Asylum called us at the Peaches Records and Tapes on Peachtree to say he was bringing Cocker by to say hello. Along for the ride was the great saxophonist Bobby Keys, who, ironically, died just 20 days before Cocker. We were happy to meet Cocker. After all, he was a guy, who despite his problems in years gone by, accomplished greatness that most people can only dream of. That day Cocker was politely detached; he knew Keys would regale us with stories about the Rolling Stones, Buddy Holly, Waylon Jennings and many others. Talk about a thrilled group of record store guys. Here was Keys, who played arguably the greatest sax solo in all of rock on the Stones’ “Brown Sugar.” And right beside him was his friend, Joe Cocker, who infused modern music with an inspired blend of rock, soul and blues. For just a few years, less than a decade earlier, Cocker was a captivating presence. Learning more about life as the years passed, he was happy to share the attention with a friend.

Joe Cocker’s career history is an episodic rags-to-riches-to-rags story with an epilogue proving there was always an inner strength to him. The glory of his performances at Woodstock and on the Mad Dogs and Englishmen tour far behind him, he’d continue to record new albums and maintain a busy concert schedule. His life story turns out to be of a man who got back up, never to reignite that old fire, but to remain standing, his dignity intact. The way wasn’t clear and the road had a lot of bumps along the way, but finally Joe Cocker’s career trek is duly recognized. From the legendary steel city of Sheffield to the American steelmaking powerhouse of Cleveland, Ohio, Joe Cocker has made it to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame — with a little help from a friend.

Paul McCartney wrote ‘em a letter. In late February, McCartney mailed the letter to the powers-that-be in Cleveland, making his plea in three paragraphs:

Dear Rock and Rollers,

I would like to suggest Mr. Joe Cocker for entry into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

Joe was a great man and a fine singer whose unique style made for some fantastic performances like our “With A Little Help From My Friends,” a version produced by Denny Cordell, which was very imaginative.

All the people on the panel will be aware of the great contributions he made to the history of Rock and Roll. And while he may not have lobbied to be in the Hall of Fame, I know he would be extremely happy and grateful to find himself where he deserves to be amongst such illustrious company.

With that, McCartney thanked the folks in Cleveland and wished them “all the best.” Roughly two months later, Joe Cocker was announced as a 2025 inductee for the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. There are other rock and roll acts who could use a little help from McCartney as well. The list is quite long, starting with Procol Harum, John Prine, Glen Campbell, Johnny Rivers, Los Lobos, Gram Parsons, Jim Croce, Richard Thompson, The Guess Who, and Jimmy Webb, all who brought together multiple influences that expanded the approach and delivery of the genre. Their omission is particularly galling when the likes of Kiss, Ozzy Osbourne, Joan Jett & the Blackhearts, Def Leppard and others who relied on flamboyance and histrionics have plaques on the famed Cleveland walls. But this year, the induction of Joe Cocker is proof that rock and roll’s spirit, going as far back as the late 19th century to inspire the likes of Scott Joplin, Louis Armstrong, Bing Crosby, Bessie Smith, Hank Williams, Louis Jordan and many others, is still cherished. No pyrotechnics required.

Thanks for this!

Great read - Joe Cocker broke his own trail and survived

“Pete Kelly’s Blues” is a GREAT watch