“If you ever get the chance to go to Dallas, take it from me, pass it by,” so sang Jimmy Buffett. “People do you wrong down in Dallas,” the song pointed out. “Dallas,” written by Roger Bartlett in 1974, had nothing to do with the pain we associate with “Big D.” Yet the tragedy and heartache still comes to mind whenever the song is played — at least ’round here.

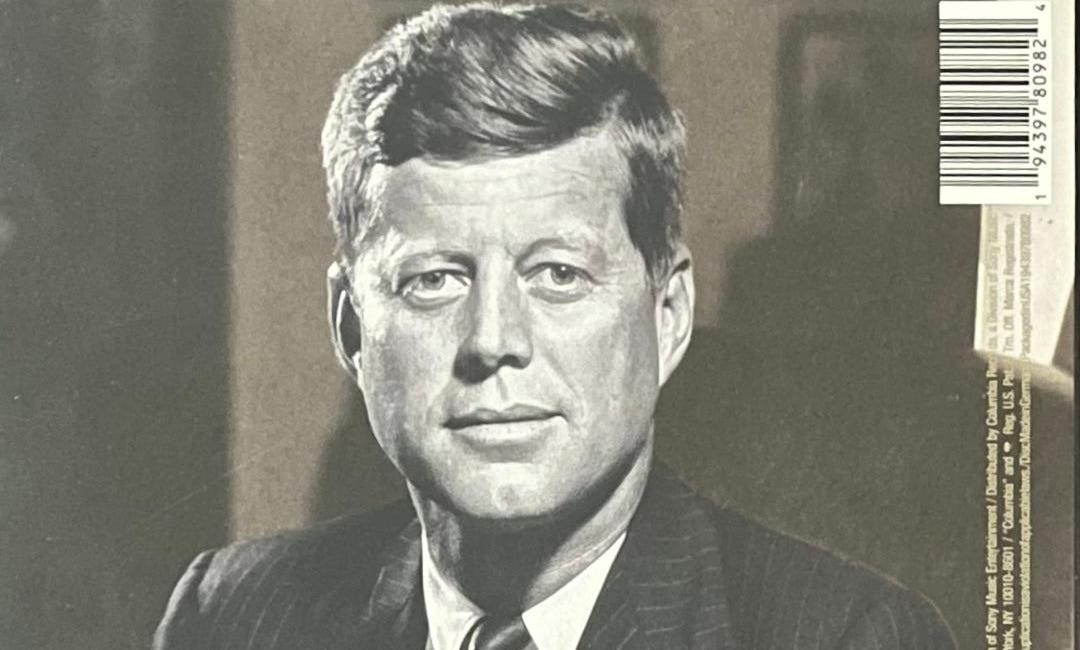

Some of John F. Kennedy’s advisers wished the president would pass Dallas by. His personal secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, told JFK of premonitions about a Dallas trip. Kennedy revealed a sense of dread as well. On Tuesday, November 19, 1963, Pierre Salinger, Kennedy’s press secretary, getting ready for a trip to Hawaii, stopped at the Oval Office to tell the president goodbye. Feeling tired and torn, JFK looked up at Salinger and said, “I wish I weren’t going to Texas.” He had told Senator George Smathers “I hate to go out to Texas” just the day before. Salinger, trying to boost his boss, told him not to worry about it. “It’s going to be a great trip and you’re going to draw the biggest crowds ever,” Salinger said. So to Texas and its political “hornet’s nest” he would go. A three-day trip covering the most populous areas of the state was set, November 21-23. JFK needed Texas badly in order to to win reelection the next November. But even under the best circumstances, a Texas victory wouldn’t be easy. Making the chance of victory tougher was the state’s rancorous Democratic Party. The mood was ugly: Right-wing versus left-wing, and Kennedy was stuck in the middle. The presidential touch, however, could ease the hard feelings. It was thought JFK would come out of it looking good. Texas Governor John Connally told his wife, Nellie, that Texans would love Kennedy when they got to see him up close.

JFK would go to Dallas, but he was annoyed that his vice president, Lyndon Baines Johnson, long a powerful politician in the state, couldn’t resolve matters; surely he still possessed that much clout. Johnson was simultaneously elected to the U.S. Senate and to the vice presidency in ’60, due to some arcane Texas law). As it was, a heartbeat away from the presidency or not, Johnson was hated by Texas U.S. Senator Ralph Yarborough, who didn’t want to ride in the motorcades with the vice president. Kennedy told Smathers, “They’re all prima donnas of the biggest order, and they’re all insisting they ride either with me or Jackie. The law says the vice president can’t ride with the president …. I just wish to hell I didn’t have to go.”

Though he thought of himself as far more popular in the state than JFK, Governor Connally was right about the acclaim Kennedy received from Texans on a trip that was suddenly more celebration and less political exercise. The president was greeted as a beloved figure in San Antonio and Houston on November 21 and with much enthusiasm the next morning in Fort Worth.

Still the president was doing a slow burn as Air Force One made the quick hop from Fort Worth to Dallas around noon. Politically, Dallas was dominated by the far-right, not just your average conservatives of the time. The local media reflected that temperament and enhanced it with wild accusations to convince Texans that the Kremlin, via Kennedy’s appeasements, was a threat to their commerce, the Southern Baptist Convention, their oil wells, and their meaty bowls of chili.

In Dallas 1963, Bill Minutaglio and Steven L. Davis describe JFK’s frustration with the far-right reporting in the Dallas media:

“It’s bad,” he says, holding up a copy for his team to see. “What’s worse, it’s inaccurate.”

General Godfrey McHugh, Kennedy’s personal military aide and the Commander of Air Force One, comes to the tail-area compartment and overhears Kennedy.

If you think that’s bad, Mr. President, wait till you see The Dallas News,” says McHugh.

“I have seen it,” replies Kennedy in his thick voice.”

His “I have seen it” conveyed not only his opinion of a full page ad The Dallas Morning News published that day, but his frustration at how the leading metropolitan daily in a major American city had become a proponent of a fringe element, wrapping itself in the flag, but using lies to cast doubts on the legitimate actions of the sitting President of the United States. Publisher Ted Dealey approved the ad, managing to make some money on the continuation of some charges he had made against the president while at The White House shortly after JFK took office in 1961. Dealey made an unpleasant guest and an even worse host.

Among the conjured accusations in the ad:

WHY have you ordered or permitted your brother, Bobby, the Attorney General, to go soft on Communists, fellow-travelers and ultra-leftists in America while permitting him to persecute loyal Americans who criticize you, your administration, and your leadership?

WHY has the foreign policy of the United States degenerated to the point that the C.I.A, is arranging coups of and having staunch Anti-Communist allies of the U.S, bloodily exterminated?

WHY has Gus Hall, head of the U.S. Communist Party praised almost every one of your policies and announced that the party will endorse and support your re-election in 1964?

WHY did you host and entertain Tito--Moscow's Trojan Horse--just a short time after our sworn enemy, Khrushchev, embraced the Yugoslav dictator as a great hero and leader of Communism?

WHY have you scrapped the Monroe Doctrine in favor of the "Spirit of Moscow"?

The ad closes with The American Fact-Finding Committee, which paid Ted Dealey’s newspaper for the space, demanding answers from the president — “NOW.” Providing answers could have been amusing for JFK. For example, Bobby Kennedy, and President Kennedy’s C.I.A. had been involved in plots to kill Fidel Castro, leader of Cuba, a communist nation. Then we have Yugoslavian President Tito described as “Moscow’s Trojan Horse,” despite Yugoslavia, under his leadership, being non-aligned with the USSR since 1948. As for Gus Hall, the general secretary of the Communist Party USA from 1959 through 2000, and four times the party’s presidential nominee, his support of a JFK presidential campaign in 1964 was understandable given that Barry Goldwater, the assumed Republican nominee, had spoken of lobbing a bomb into the Kremlin’s men’s room. The ad featured more farcical accusations in which genuine answers would serve as embarrassments to The American Fact-Finding Committee, but they were like the Trumpers of the ‘60s. They hurled accusations. Their accusations were shot down, but they dug in deeper, continuing with their delusional behavior. Perhaps they inspired the likes of Marjorie Taylor Greene, who has built her political career spreading ludicrous and diverting lies.

As for Goldwater, who eventually concluded the Republican Party had been taken over by a “bunch of kooks,” he considered JFK a friend despite their political differences. Once when Goldwater visited The White House during the botched Bay of Pigs invasion, JFK caught him sitting in the presidential rocking chair. Kennedy asked, “Barry, do you want this fucking job?” Such bantering helped ease the mindsets of political opposites when working their way through an existential crisis. But there was no sarcastic bantering from the so-called American Fact-Finding Committee in Dallas. No, they were more like the “Hang Mike Pence” crowd of our current political season. The rabble, it seems, is always among us.

By 28 minutes past noon (CST),November 22, 1963, it seemed a charming and articulate young president, accompanied by his gracious and lovely wife could emerge successfully from a tense day; the rabble be damned. The trip appeared a triumph. The crowds were huge. Kennedy was cheered wildly. Nellie Connally, while in the motorcade on the way to the luncheon at the Dallas Trade Mart, said to JFK, “You sure can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you, Mr. President.” Smiling, JFK answered, “No, you can’t.” A couple of minutes later, Kennedy, still smiling, raised his hand to wave at a five year-old boy. Then shots rang out.

At Top 40 station WIL in St. Louis, Missouri, bells rang out. 15 bells on the UPI ticker. A news flash, as defined by the wire service. It was 12:39 pm, Central Standard Time. Shots had been fired at the Kennedy motorcade. President Kennedy had been seriously wounded in the shooting. Larry Kane, handling the news at WIL, went on with the flash, then threw the programming back to the deejay, ready with a Bobby Rydell song. That was the last of the Top 40 sounds for the next 3-4 days. Kane went back on the air with the news, which was getting worse by the moment. Kennedy was dead.

Ironically enough, most of the WIL staff was out for a celebratory lunch. The station had scored big in the recent ratings, and it was party time. So in arguably the country’s most critical moment of the 20th Century, Larry Kane, only 21 at the time, was left to his own devises as he took to the air, adlibbing as a secretary kept ripping wire copy for him to read over the air. When the rest came back, Kane put on some music from the FDR funeral a station engineer had found in the vault. Then Kane headed off for the rectory of St. Louis Archbishop Joseph Ritter, to speak with him about the tragedy in Dallas.

The mourning over Kennedy’s death and the grieving for America itself took a toll on the country, but life would go on. On the day John F. Kennedy was laid to rest, there were only 30 shopping days left before Christmas. There were gifts to buy, commerce to conduct and NFL games to be played. In fact, as an indicator of how important the NFL considered itself, its games were played two days after Kennedy’s assassination. The nation’s new president began sketching out plans to win election the next November. Life goes on faster for some than others. For Larry Kane, with more than another 50 years in American media ahead of him, life was moving at a promising clip. On December 27, 1963, he began a drive from St. Louis to Miami to take over the job as News Director at radio station WFUN. A big year was ahead.

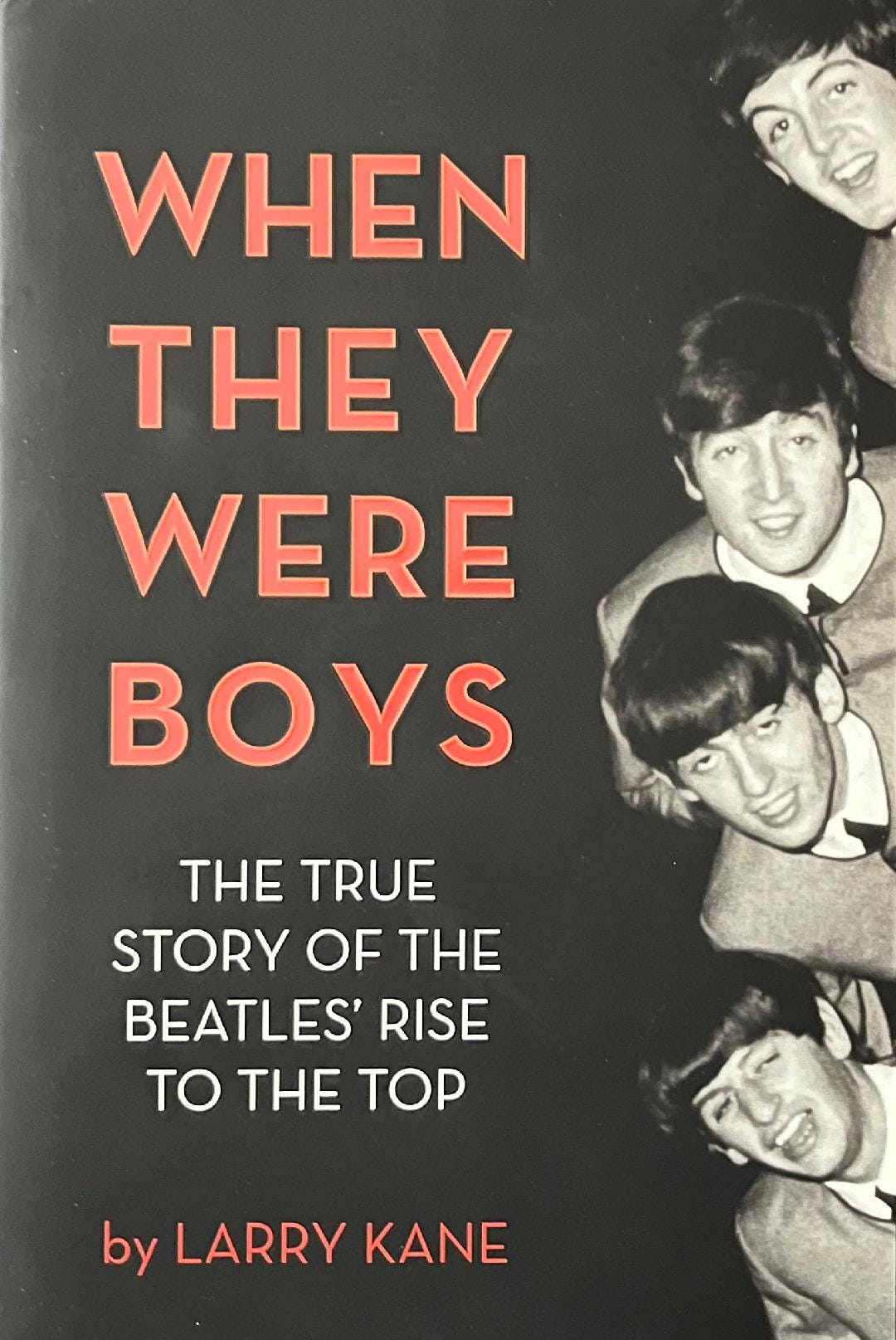

On his trek from St. Louis, through Paducah, Kentucky and Nashville, Tennessee; then down into Georgia and Florida, Kane heard “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” by The Beatles, a band from Liverpool, England, heretofore unknown in America, on nearly every Top 40 station he dialed. By the time he reached Florida, he also heard “I Saw Her Standing There,” Love Me Do,” and “She Loves You” by The Beatles. As Kane wrote in his 2013 book, When They Were Boys, The Beatles “were everywhere.”

On February 7, 1964, The Beatles flew into New York and were welcomed wildly to America at the newly-renamed John F. Kennedy International Airport. Two days later, fans of the group, and those simply curious about them, altogether 73 million Americans, watched the Beatles — John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr — perform five songs on The Ed Sullivan Show. A few days later The Beatles flew down to Miami where they made their second of three scheduled appearances on Sullivan’s program. On hand to interview The Beatles as they relaxed and took in the sun was Larry Kane. At the time, Kane wasn’t convinced The Beatles were a keeper. Maybe they were just a fad. But having been the first American correspondent to break the news of the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba in April ’61, Kane knew all about staying on a hot story — and The Beatles were that. So stay on he would, on each of the stops of their American tours in the summers of ’64 and ’65 as well as joining them in St. Louis and New York in summer ’66 during their final concert tour.

The Beatles helped ease the pain millions of American youth still felt over the loss of their young, charismatic president. Those of us who bought magazines and books commemorating JFK’s life and covering its tragic end soon found ourselves not only buying records by The Beatles, but also magazines, posters, bubblegum cards and on whatever else their images were set. All the while, The Beatles became interested in the political scene of the nation that had taken so much interest in them.

While flying over America, The Beatles read up on issues such as the Kennedy assassination, the civil rights movement and Vietnam. In that summer of ’64, not many Americans were paying close attention to America’s involvement in the Vietnam War. The incumbent president, Lyndon Johnson, campaigning to win election in his own right, declared the United States wouldn’t get bogged down. He promised voters that “We are not about to send American boys nine or ten thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves.” All the while Johnson had Congress pass the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution which authorized the president to assist any nation in Southeastern Asia, like South Vietnam, whose government was threatened by communist aggression. That gave Johnson as commander in chief a lot of leeway. And that rankled John Lennon. When asked by Kane what he thought about Vietnam, Lennon delivered a “scathing diatribe” against the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, which had just passed 12 days earlier. Kane said he “was taken aback by the intensity of his anger and knowledge base, and also by the eloquence of his protest.”

Kane, in When They Were Boys, writes that Ringo Starr was actually the most outspoken of The Beatles, among those with whom they confided, in opposition to the U.S. escalation of the war in Vietnam. Kane remembers that Starr’s “intellectual curiosity was as deep as John Lennon’s.” But it was Lennon, according to Kane, even in the lovable mop-top days, who had “the soul of an activist building up in him.”

In an earlier Kane book, Ticket to Ride, Kane wrote that Paul McCartney, as well as Lennon, was “looking a bit fidgety” as they flew to Dallas for a concert on September 18, 1964. McCartney had spoken highly of President Kennedy and the absurdity of the assassination, calling it “idiotic.” JFK “was creating a great image for America … and he seemed to be doing great things.” The polar opposite of JFK’s image, in Lennon’s mind, was Dallas, where Kennedy — and his assassin — were killed. Lennon asked Kane, “Ever been to Dallas?” Kane said just once, a brief stop. “A lot of guns, huh?” Lennon asked. The Beatles knew Kane as quite the young reporter, but they viewed him as a keen observer when speaking of his country. And he understood how they felt. In Ticket to Ride, he wrote:

To many Europeans, Dallas exemplified an America run by lawless cowboys who roamed the West looking for easy money and victims to murder. As I prepared my reports for the next morning, I noted that the Beatles seemed genuinely afraid of what was to come in Dallas. Their fears, as it turns out, were unfounded, but considering the state of America on September 18, 1964, who could blame them?

Dallas did little to enhance its image on The Beatles’ visit. When they arrived at the Cabana Motor Inn (owned by Doris Day, according to Kane), they saw the Dallas police brandishing their rifles openly.

… this was the first time the Beatles had seen rifles at the ready. I got the impression that we would be well protected on this leg of the tour, but the raising of the rifles only reinforced the anxiety that the Beatles were feeling. The expressions on their faces, their eyes wandering around, gave me the feeling they were concerned about their safety.

There were phoned-in death threats, one aimed at the Dallas Coliseum and another at The Beatles’ plane. There was nothing to the threats, but it was all part and parcel of life we were getting accustomed to in America — and that we’ve been cruelly reminded of over and over again since. The cruel violence would spread in every direction from Dallas. Malcolm X. Martin Luther King, Jr. Robert F. Kennedy. The victims in the murders of Richard Speck in Chicago and the Manson Family in Los Angeles. Harvey Milk. George Moscone. And John Lennon, who came to love America and call it home, in New York City.

The spirited voices of those singing “Give Peace A Chance” remain strong, but are too often drowned out by the sound of gunfire in houses of worship, theatres, schools and throughout the walk-a-day life, such as earlier this month when a mother and her infant son were both injured by gunfire as they slept in their home just east of Atlanta. Thankfully, mother and child are expected to fully recover, but even though the two were not the intended targets in the shooting, there is still cause for worry in their suburban neighborhood, where, as in so many areas of Metro Atlanta, tragedy can strike when individuals believe arguments can only be settled with guns.

Atlanta, a booming southern city, is beset with the highest income inequality among large U.S. cities. Its metropolitan area, with a large portion of the populace toting guns in case there’s a score that needs settling, is also surrounded by rural enclaves less than 50 miles away where devotion to the Second Amendment runs high. Violent tensions and a grandiose sense of entitlement are a bad mix, making for too many among us who won’t give peace a chance.

Despite our wealth, education, and spiritual awareness of varying degrees, mindless cruelty, often observed indifferently, goes on. Histories of violence and “a lot of guns” are with us everyday. As Walter Cronkite, who delivered the sad news of Dallas to the nation 60 years ago, told us each night, “And that’s the way it is.”

Bob Dylan: President Kennedy Was Riding High

President Kennedy was riding high Good day to be livin’ and a good day to die In the third and fourth lines of “Murder Most Foul,” Bob Dylan offhandedly and succinctly imparts what millions of us know about November 22, 1963. The twenty-four hours before Lee Harvey Oswald fired his mail-order rifle were good ones for President John F. Kennedy. In a way, he…