Papa John Creach in the Golden Ghetto

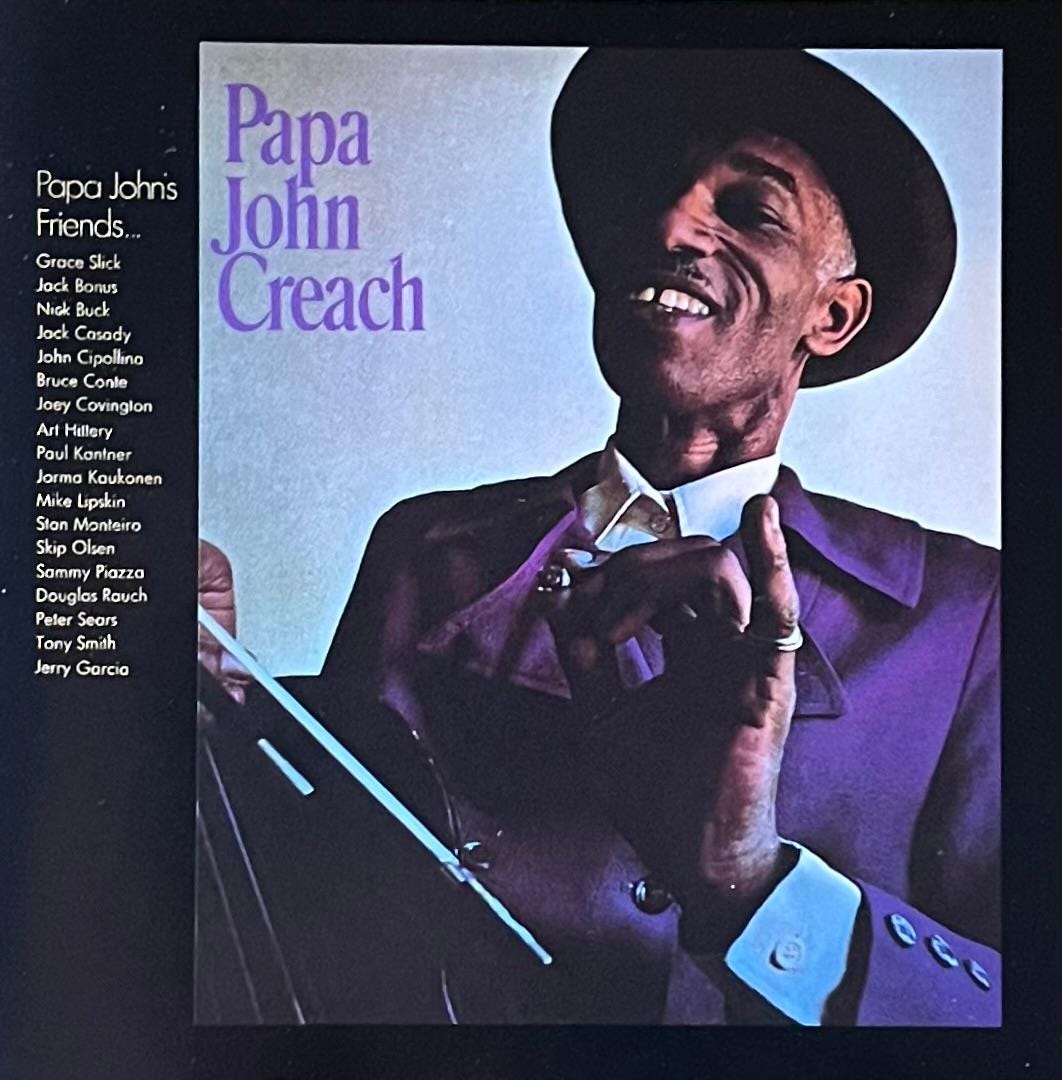

Julia Cade, the Music Editor of The Great Speckled Bird, was on the line. “I have an assignment for you,” Julia exclaimed,”an interview with Papa John Creach!” Hey, that’s right, I remembered; Papa John, the great blues violinist, was playing that week at The Great Southeast Music Hall. He had a new band and a new album on a new label thrilled to have him on board. Even if he wasn’t touring with the Jefferson Starship this time around, Papa John Creach was flying high. And so was I. Just two years earlier, in 12th Grade English, my friends and I would talk rock, blues, the Allman Brothers Band, Hot Tuna and Papa John. Now, in September 1975, Papa John would talk with me and the interview would appear in one of the nation’s best-known alternative newspapers. Even my grumpy English teacher would’ve been impressed.

Finishing up the conversation with Julia, I asked where the interview would take place. “At the Guest Quarters, on Roswell Road, in Sandy Springs,” Julia responded. Sandy Springs? Around that time, Al Kooper had a home in Sandy Springs, located on Heards Ferry Road, in a very plush, woodsy enclave of the unincorporated area known as the “Golden Ghetto.” Over the previous decade Sandy Springs was the White Flight destination just north of the Atlanta city limits and its tonier neighborhoods. The people in Sandy Springs were fine with their proximity to Atlanta’s northside neighborhoods but were opposed to annexation by the city, especially since the ’73 election of Maynard Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor. Despite Jackson’s smarts and sophistication, to biased whites, Fred G. Sanford might as well be mayor. Politically, they wouldn’t have been happy with Al Kooper either. In the summer of ’73, he gave a benefit concert at the Music Hall for City Council candidate James Bond, brother of Julian.

Sandy Springs was a long way, 887 miles, from Brooklyn, New York, birthplace of Al Kooper, but some 170 miles closer is Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, where on May 28, 1917, Papa John Creach was born. A rustbelt town that experienced more than a half-century of decline, Beaver Falls is best known as the birthplace of football legend Joe Namath. In the part of Beaver Falls where Namath grew up, the Lower End, the majority of the population was African-American. He empathized with the plight of Black Americans, which made him suspect to some of his University of Alabama Crimson Tide teammates in those peak years of the nation’s civil rights movement.

Much had changed in the decade since Namath left Tuscaloosa, Alabama. The kid from Beaver Falls, known to most of the country as Broadway Joe was only 32, but due to bad knees, his NFL career would be over in a couple of years. Namath could count on his well-earned fame to keep him comfortably busy as a football commentator on network TV while also getting a few acting gigs. Papa John Creach could only be happy for the star from his hometown, but in the words of Bob Dylan, he was “still on the road, headed for another joint.” Clearly, the Great Southeast Music Hall was a pleasant enough joint to earn some cash and the lodging in the Golden Ghetto was a leisurely spot for Creach to stretch out his lean 58 year-old body. This stop along the road would be fine.

Papa John Creach looked rested and happy the day I made it to his suite at the Guest Quarters. He was a man happy with his lot in life, the partnership with his wife, Gretchen, and the joys that music had brought to him. As far as he was concerned, there was lots to celebrate, especially a reunion of fellow band-mates:

“Yeah, I was partly responsible for getting Marty back with the Starship. I call him up now and then and I used to tell him not to let his voice go to waste. I was afraid he might lose it. And so finally he came back with us.”

Of course he was talking about Marty Balin rejoining Grace Slick, Paul Kantner and himself with the Jefferson Starship. At the time, the band was enjoying success with their latest album, Red Octopus, which featured the ubiquitous hit single, “Miracles.” But even with the multi-platinum status of Red Octopus and the Starship being a far bigger attraction than in their earlier incarnation as the Jefferson Airplane, Creach decided to leave the band in order to focus on a solo career. “It became too much,” he said, “I needed to slow down. I’d record with the Starship, go out on the road with them, the same thing with Hot Tuna, then I’d do my album and a tour of my own. It became monotonous; besides I’m 58 years old.”

58 years old may have seemed ancient then in the world of rock and roll, but Creach possessed a youthful energy that was infectious. He was particularly excited about his new band, Midnight Sun. “What I like about this band,” he declared, “is they rehearse five days a week for about four or five hours a day. You can’t go wrong that way. They jump around on stage, they’re young and inquisitive, wanting to learn.”

Creach was very happy about his new album, I’m the Fiddle Man, and the gigs ahead, but he loved talking of the old days and his more than 40 years of making music. He spoke of the Depression years when he and his bands played the hotel and restaurant circuit. Asked if he, a Black man, playing the violin threw off the audiences, he replied, “Yeah, the Black people would say, ‘Oh no, Jack Benny!’ But then I’d start playing and they’d be yelling for more.”

Moving from Pennsylvania to Chicago with his family in 1935 was the first break in Creach’s musical career. He studied violin at the Conservatory of Music and eventually got a WPA job with the Illinois Symphony, serving as music librarian and occasionally as a guest artist. Though he continued to study and play classical music, it was a musical genre difficult for a Black man to make a living at in those times, so it was on to the clubs and dance partys that paid the bills.

Having studied the classical greats as a child, he learned the finer details involved in playing the violin. “I can pick a G-7 apart, ” he said, a bit scholarly. “It’s great to know what a note is when you hear it and in doing so, I’ve been able to create my own style.” His creativity went to the next level while playing with such blues greats as Roy Milton and T-Bone Walker in the ’40s when he began to “experiment around” by amplifying his violin. That Creach experiment may have been what brought him to rock and roll and the band he called the “Airplanes.”

In 1945 Creach moved to Los Angeles where he continued to study and play classical music at symphony workshops. At night, for most of the next 20 years, he’d play jazz in cocktail lounges. A highlight from that 20 year period was his appearance in Fritz Lang’s 1953 film, The Blue Gardenia. Creach plays violin as Nat King Cole sings “Blue Gardenia” in a Polynesian restaurant called the Blue Gardenia where the men buy blue gardenias for their dates. As Cole sweetly sings, Raymond Burr plies Anne Baxter with drinks, hoping to put her in a tropical island mood. Across the room from Burr and Baxter, Creach, graceful and stoic, plays behind Cole, but on screen, is mostly visible through the mirrow tilted above Cole’s piano. In keeping with the restaurant’s theme, both Cole and Creach wear Polynesian leis around their necks. For Cole, already a big star, this was just more exposure as his career was ascending. And for Creach, in a way, it was just “another joint,” even if it meant being seen with the stars. Appearing in a film directed by Lang with Burr, Baxter and Cole was glamourous work and a terrific reference but it was the lounges and clubs, not the movies, that provided Creach regular employment.

The next phase in Creach’s career began in 1967. Recalling how things fell into place, he said, “I was down at the musician’s union office, looking for jobs on the bulletin board. It was then that I met Joey Covington and we talked about forming a band that never materialized, but three years later I heard from him and he told me he was going to be the new drummer for the Jefferson Airplanes. Then I was called by the group to play a concert with them at Winterland and then another in Texas. From there I became a full-time member of the Airplanes.” It was a big break for Creach. “Right away, there’s all this exposure, but still it wasn’t something I jumped flat-footed into,” he explained. “I had listened to their albums, just like I had listened to The Beatles and Hendrix, so I knew rock and roll.” Playing with the Jefferson Airplane was an easier fit for Creach than people may have thought. “I’d just look at the charts and add my own licks. We never had any difficulties.”

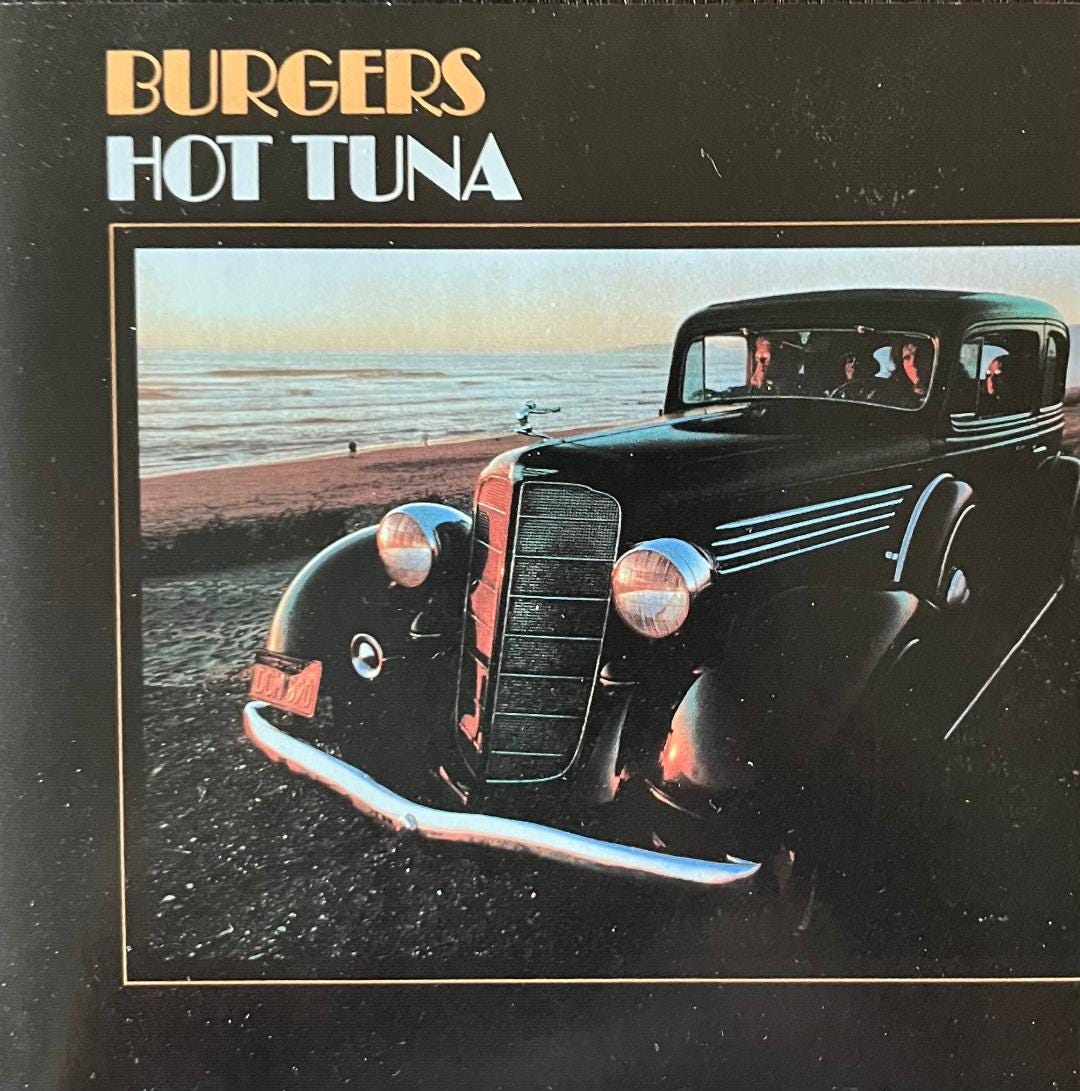

Creach was a consummate professional and would give it his all, even on such overwrought and pompous Jefferson Airplane songs as “Crown of Creation” or “Volunteers.” There would be, after all, opportunities for his licks to soar and take hold, as with “Pretty As You Feel,” off the band’s Bark album in ’71. The grandest opportunity the Airplane provided Creach, however, was getting to work with guitarist Jorma Kaukonen and bassist Jack Casady. The three kindred spirits hit it off particularly well on Hot Tuna’s bluesy and tuneful Burgers album. Presenting originals as well as decades-old blues songs by Julius Daniels and Reverend Gary Davis, Burgers displayed the band’s love and enthusiasm for America’s traditional musical genres. Listening to Messrs. Casady, Creach and Kaukonen was, to broader-minded rock fans, edifying, particularly when taking in “99 Year Blues,” the song Daniels song wrote with his guitarist Bubba Lee Torrence, and recorded by them in Atlanta on February 19, 1927. “99 Year Blues” dealt with a private insurrection, one inspired by vengence that brought on punishment not fitting the crime. For those living the blues, justice was in short supply, whether before or after running afoul of the law. Hot Tuna’s version of the Daniels-Torrence song, recorded 45 years after the original, is spirited and lively, with Creach’s fiddle playing red hot and majestic.

Now, more than 50 years after their recording of “99 Year Blues,” still undeniable is the integrity Hot Tuna conveyed, especially after enduring Jefferson Airplane’s “War Movie,” more piffle about the coming revolution from Bark. “War Movie” described an uprising among the people from the countryside, leading to the “Battle of Forever Plains,” predicted to occur four years after the song’s recording. It didn’t happen. Instead, in “nineteen hundred and seventy-five,” Papa John and Gretchen Creach were holding court in posh surroundings near the heart of “The Golden Ghetto,” graciously sharing stories of days gone by. Not all those days were golden, but Creach looked upon his life with fondness, happy for all his learning and experiences. Creach’s outlook resembled that of Buck O’Neil, the great first baseman from the old Negro leagues, who named his memoir I Was Born Right On Time.

Papa John Creach seemed to have a lot more time ahead, but he died of pneumonia at the age of 76 on February 22, 1994, a little more than a month after suffering a heart attack during the Northridge earthquake. Almost to the very end, he was “on the road, heading for another joint.” In 1992, he released Papa Blues, an album recorded with the Bernie Pearl Blues Band, all the while touring with a retooled version of Jefferson Starship. The very next year the Blues Foundation awarded him with the W.C. Handy Award. The Fiddle Man was still going strong. Apparently, only a 6.7 magnitude earthquake, one of the costlier disasters in the nation’s history, could stop Papa John Creach.