I Went Into The City, Went Into The Town .… Bob Dylan and The Band kicked off the show like a basketball team on a fast-break. Opening their concert at the Omni with “Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine),” Dylan was, in a sense, establishing his game plan for that evening in Atlanta, just as he had in other cities on his heralded comeback tour. Dylan and The Band had the ball in their court, so to speak. The 16,000 at the Omni on that January night in ’74 cheered to what was all at once a greatest hits show and a display of what’d be seen from Dylan in the years and decades to come: dazzling and intriguing performances with fiery independence and changes in presentation. Familiar songs performed quite differently than on the recorded versions. Early in the show, when Dylan and The Band bounded through a hard-driving version of “Lay Lady Lay,” some in the crowd grew restless. A young woman seated close to the stage was seriously bothered, saying, “He has a nerve, ruining his song like that.”

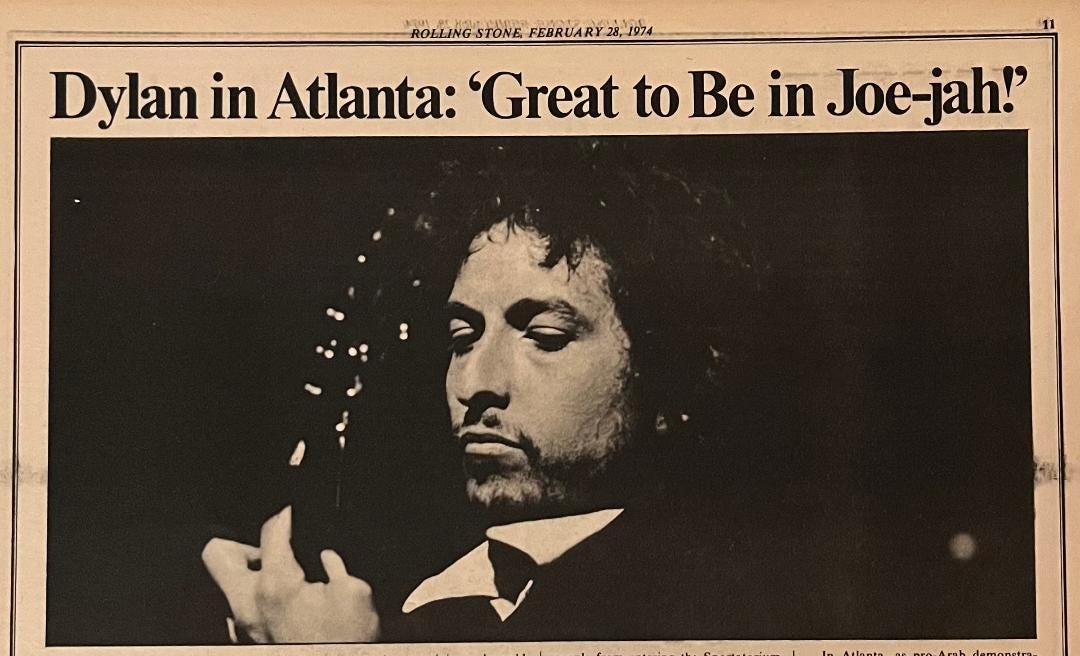

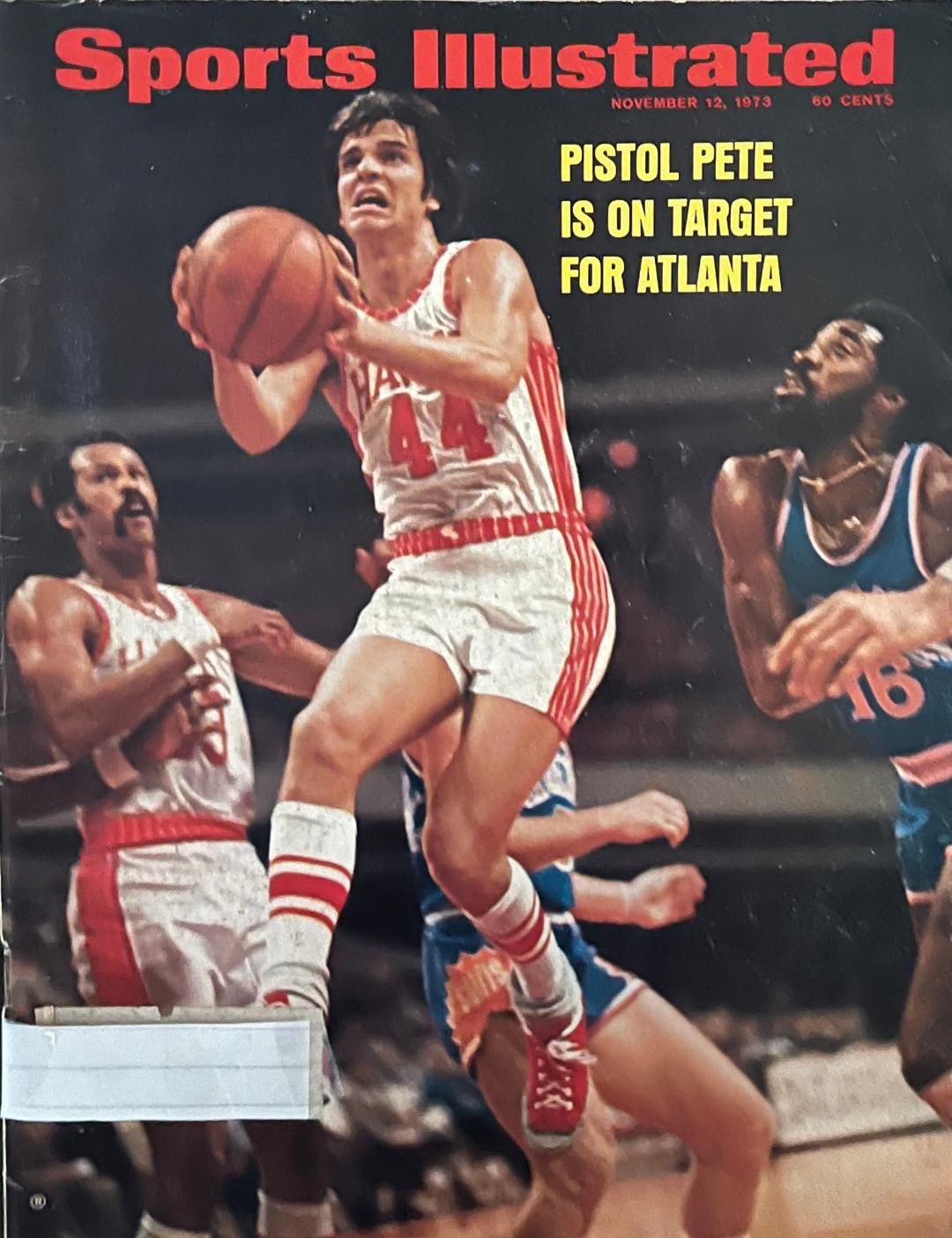

But Dylan was in command, just as Pete Maravich was in that same building two nights before. Leading the Atlanta Hawks to a victory over the Seattle SuperSonics, Maravich scored 34 points. Experiencing the best season thus far in his professional basketball career, Maravich was second in scoring in the NBA, at the time averaging just under 29 points a game. During that ’73-74 season, Dave Anderson of The New York Times wrote that Maravich was “playing basketball as nobody ever quite did before.” Given his extraordinary play at LSU several years earlier, the Maravich that Anderson saw must have been other-worldly. With his running reverse lay-ups, Maravich appeared one part Bob Cousy and one part Alvin Ailey. People were again taking notice of Maravich — they couldn’t help but not. His play still dazzled, but he was now more of a team player. His shots were more carefully chosen and his stunning passes were perfectly executed, landing where intended. For his first time as a pro, Maravich made the cover of Sports Illustrated in November ’73. In early ’74, Dylan would twice make the cover of Rolling Stone. Splendid comebacks generated the attention they deserved.

Dylan’s “comeback” as a major touring artist began in late ’73 after being off the road, save for a few select appearances, the previous seven years. It was his decision not to tour, choosing instead to concentrate on writing and recording new material while sticking close to hearth and home. Or, as he summed it up in “Sign on the Window” on the New Morning album in ’70:

Marry me a wife, catch rainbow trout,

Have a bunch of kids who call me “Pa.”

That must be what it’s all about,

That must be what it’s all about.

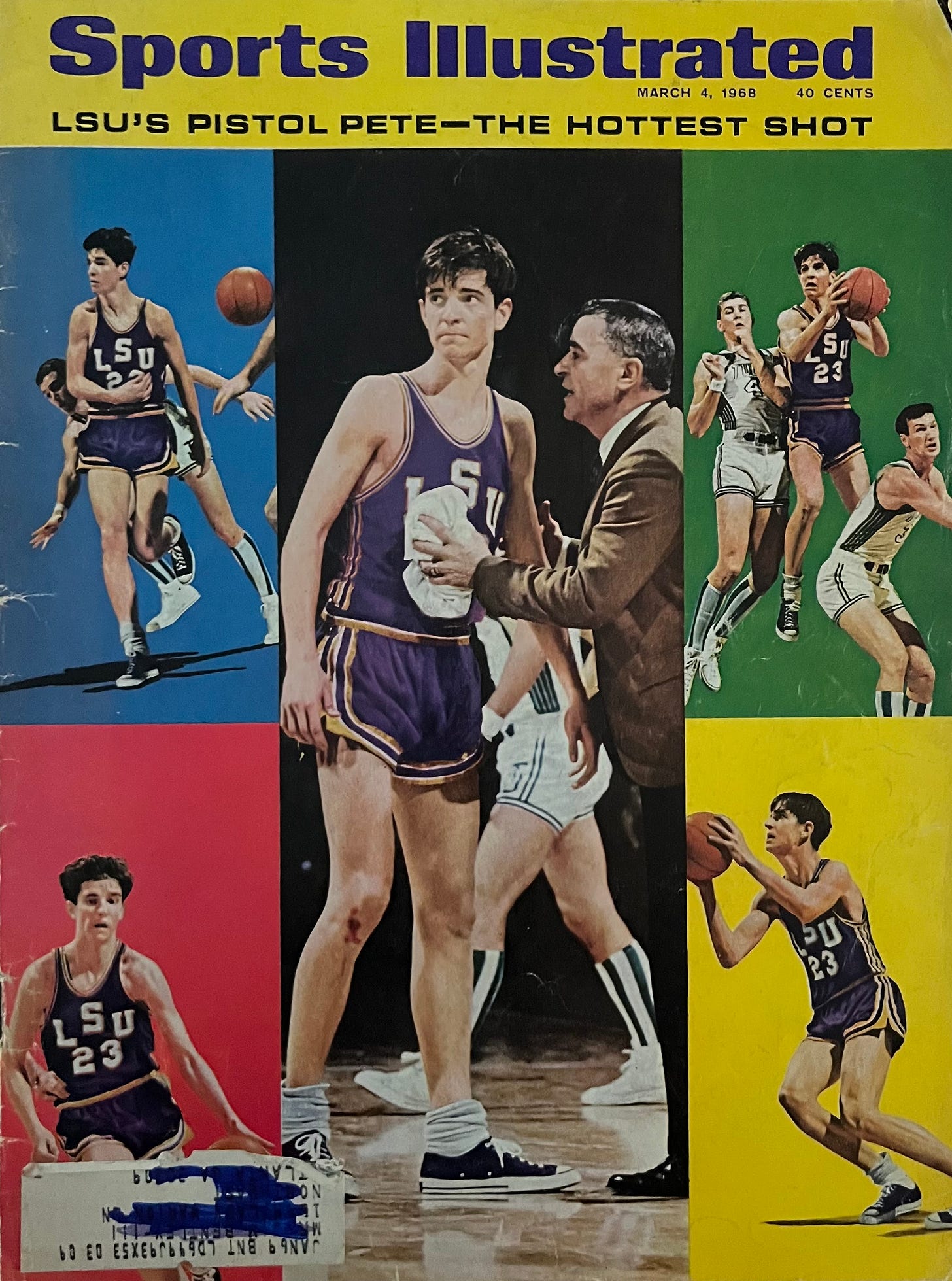

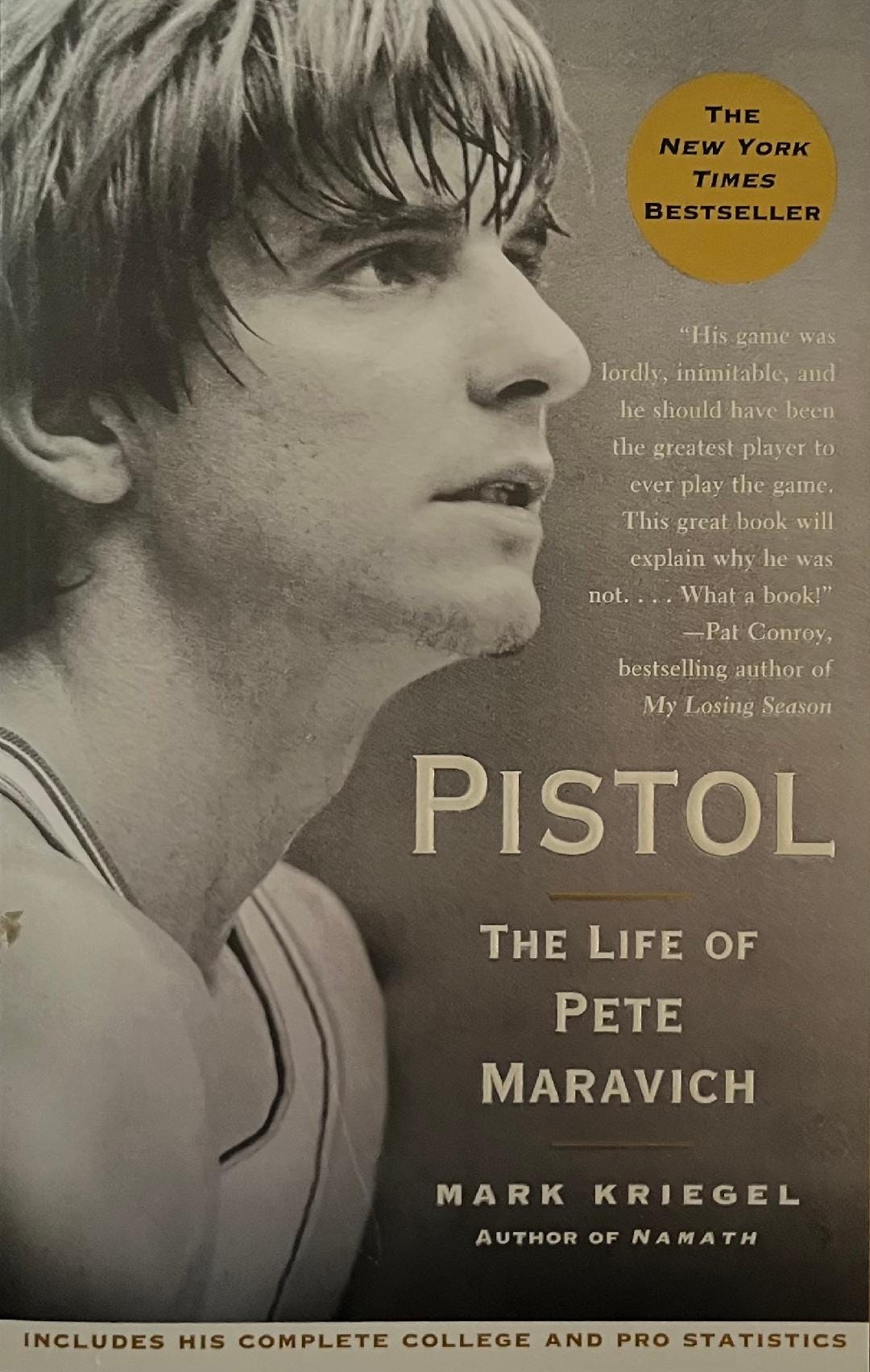

Young Man Lookin’ In The Shadows That Pass … In the years Dylan stepped away from the spotlight, Pete Maravich took center-stage in the sporting world. He built an immense national following while playing for the LSU Tigers during three NCAA seasons (67-68 through 69-70). “Pistol Pete” was unlike anything seen in the game before. In those three seasons, he scored 3,667 points (in the years before the 3-point shot), averaging 44.5 points a game. More than five decades later, many of his NCAA records still stand.

But Maravich had his critics. Tough critics. His games for LSU, coached by his father, Press Maravich, were often one-man shows. And Pete took a lot of shots, often wildly, making for a less than average shooting percentage. Basketball is a team effort and the Maravich approach seemed the antithesis of the way the game should be played. Yet Maravich put LSU on the college basketball map. The school got a new basketball arena and, most importantly, LSU compiled a winning record during the years Maravich suited up for the Tigers. In the season prior to Pete taking the court, the Tigers went 6-23.

Yes, the guy had his critics, but with Maravich in the game, it was always Showtime. In a golden era for college basketball (Lew Alcindor, Elvin Hayes, Wes Unseld and Earl Monroe were among those transforming the game), Pete Maravich was the flashiest and most sensational player in America.

Among the most dismissive of Maravich critics at the time was Richie Guerin, the coach of the Atlanta Hawks. Guerin had already enjoyed a career as a pro basketball player which would land him, finally in 2013, in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Guerin, after seven years in the Marines, joined the New York Knickerbockers in 1956, kicking off an NBA career which included six seasons as a league all-star and recognition as Coach of the Year for the 67-68 season with the Hawks, then playing in St. Louis. He had been flashy in his playing days and a favorite of fans and reporters. Guerin always had something on his mind and to the delight of his sportswriter friends, he was free with his thoughts.

A few months after the Hawks moved from St. Louis to Atlanta, the team’s new owner, Tom Cousins, spoke in glowing terms to Guerin about Pete Maravich. “I don’t know if he’ll ever make it the NBA,” Guerin told Cousins, who had made his fortune in real estate development. Cousins was willing to let the basketball guys run the Hawks, but with one exception: ” … if we ever have a shot at this guy Maravich, I want him.” Guerin’s retort about Maravich not being NBA material didn’t discourage Cousins, who responded, “He’ll make the sport in Atlanta, Georgia.”

I Went Into The Red, Went Into The Black … What the great music producer Sam Philips found in Elvis Presley — the realization of his dream artist, “a white man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel” that could make him “a billion dollars” — many basketball people, including Tom Cousins, saw Maravich as a Great White Hope for the game. With Maravich packing them in, Cousins could build an arena in downtown Atlanta. There Maravich could practice his wizardry as the money poured in and the people of Atlanta embraced a sport that was increasingly regarded as the domain of Blacks.

For the ’69-70 season, their second in Atlanta, the Hawks, with a record of 48 wins and 34 losses, won the Western Division title. There in Atlanta, where segregationist Lester Maddox served as Georgia’s governor, the Hawks, with an all-Black starting line-up, impressed those, be they Black or white, who loved the beauty and precision of the game. Those Hawks were not a running club but they were a well-rounded and tough unit that played as a team. Think of them as blending and working with each other as did Duke Ellington and his Orchestra on Such Sweet Thunder. As in Ellington to Hodges to Gonsalves went Bridges to Hazard to Hudson.

Subtlety, muscle, timing and the sudden swift move made those Hawks a joy to watch — and one of the best teams in the game. But in a town like Atlanta, swaggering but always insecure, the next big thing — and the riches that come with it — prevailed. So in March ’70, the Atlanta Hawks signed Pete Maravich to what was reported as the richest contract in the history of sports. Changing his tune somewhat, Guerin told UPI, “Drafting Pete Maravich is good business.”

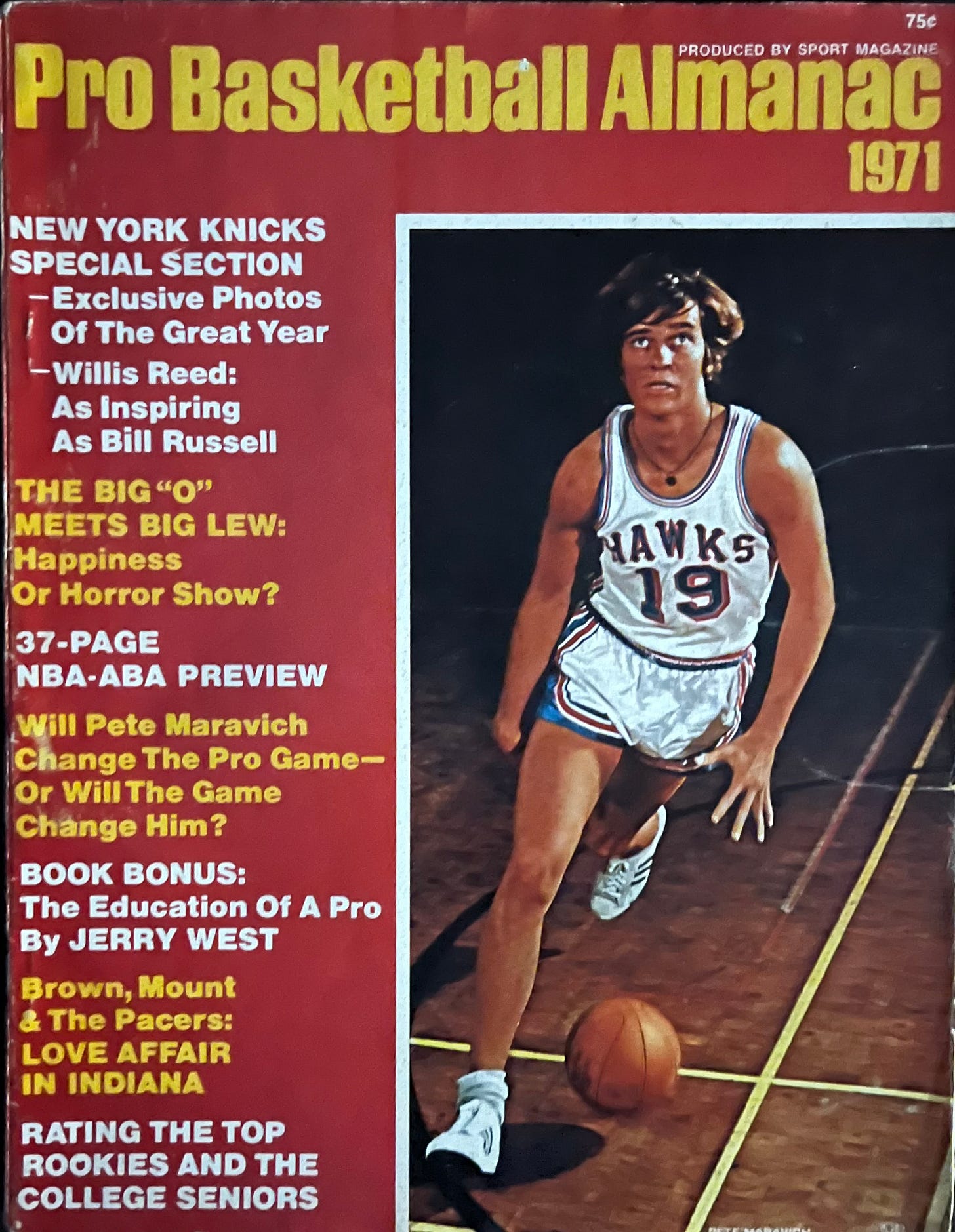

Business, at least as measured by attendance at Hawks games, did pick up. With winning records in their first two years playing at Georgia Tech’s Alexander Memorial Coliseum, the Hawks averaged 188,484 fans per season. In the ’70-71 season, the first with Maravich, attendance climbed to 245,910. That’s despite a losing record, which was quite often blamed on Maravich. Even with his skills, Pistol Pete didn’t fit in with the Hawks’ approach to the game. It was easy for him to be a one-man show at LSU, given the quality of Southeastern Conference basketball in the late ’60s. At LSU, he would pick up his teammates, while the weaknesses of the opposition were easy for him to exploit. But now Maravich was in the NBA, where players and thoughtful observers believed he should adjust to his team’s style — a winning style, after all — as opposed to the team adjusting to his.

Bill Bridges, the Hawks’ captain and one of the finest forwards in the NBA, was among those frustrated by Maravich’s approach. Still, he knew quite well why the Hawks wanted him. On the day after Maravich was drafted by the Hawks, Bridges told Atlanta Constitution beat writer George Cunningham, “Let’s face it, a white player of his ability is what Atlanta and the NBA need. He may be the greatest gate attraction to come in the league and that doesn’t hurt. It could mean a couple of extra hundred thousand dollars for all of us Hawks … I like playing before a crowd … More people, more money.”

Into The Land Of The Midnight Sun … Guaranteed more than $1 million, Pete Maravich rolled into Atlanta in his new Plymouth GTX, adorned with $2,000 in options, including a top of the line sound system. The decor of his new apartment suggested Jethro Bodine meets the Jetsons. Maravich was a rich, good looking young man long used to making headlines, but now he would do so in Atlanta, a great distance in many ways from Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Atlanta was a city on the rise, more progressive than most of Georgia, where for some, old times were not forgotten, especially when the memories included Jim Crow laws, lynchings, and poll taxes. And with Lester Maddox as Georgia’s governor for a few more months, reminders of history’s shame would still obscure the flash and dash Atlanta yearned to convey. Atlanta was playing Showtime too. Its new skyscrapers and hotels left visitors awed, astounded and sometimes speechless. Such was the case at the Regency Hyatt House, designed by John Portman. At the top of the Hyatt was a restaurant shaped like a flying saucer. Very slowly, it rotated, as patrons viewed the city atop 22 stories. Not far from the Hyatt was the Midnight Sun restaurant, in one of Portman’s Peachtree Center buildings. More glamour. Lots of chrome and leather. It was the type of place Maravich might hope to find Dyan Cannon waiting for him.

But if Ms. Cannon sought Pistol Pete’s attention, she’d have competition. Not only did the teenyboppers adore Maravich, but so did the ladies who didn’t have to tell Dad where they’d been all night. Then, given his athletic prowess, Maravich was also an obsession for many young basketball players in Metro Atlanta. John Carbo, a fierce rebounder for the Forest Park Senior High Panthers basketball team, remembers that “in the early ’70s, every white kid in the Atlanta area, high school and younger, copied Maravich. From the floppy socks, to the shooting style, to his ball-handling magic.” However, the attempts to duplicate the Maravich moves, said Carbo, now a retired state judge in Georgia, were, “feeble.”

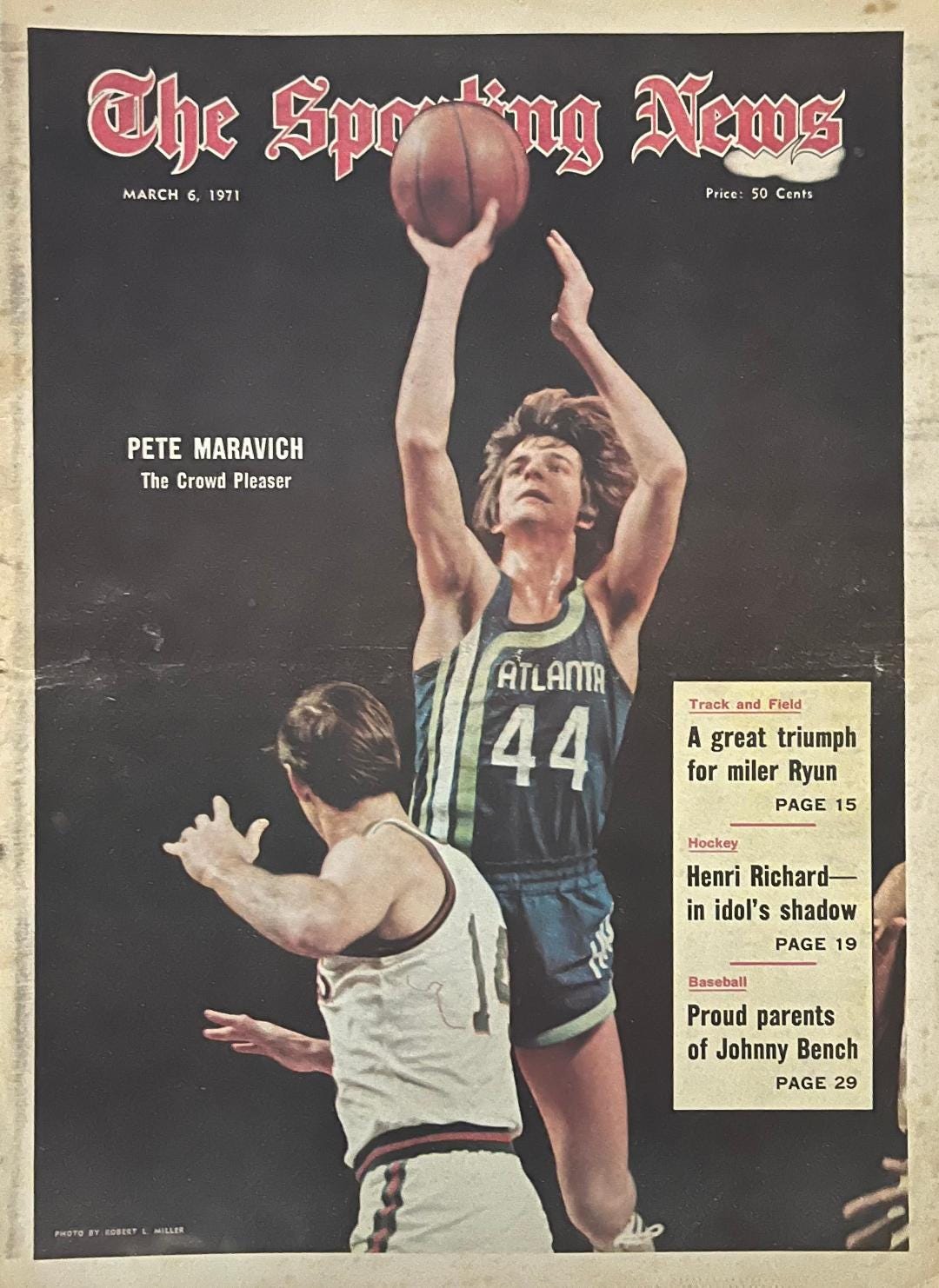

The ball-handling magic was left to the master, and he dazzled the adoring crowds at Georgia Tech’s cozy coliseum. Maravich enjoyed putting on his shows, but sharing the stage was team dissension. A cover story in The Sporting News by George Cunningham was headlined “Crowds Love Pistol Pete But Players Don’t.” Cunningham wrote, “Despite $2 million and youth on his side, Maravich does not appear to be a happy man.”

Down Where The Vultures Feed … Atlanta teammates felt Pete too often played as if he were the only Hawk on the court. According to Cunningham, Hawks players were “particularly disgusted” with Pete’s “early season habit of getting the ball in-bounds and then dribbling until he either got trapped in the corner or found an opening for a jumper 30 feet from the basket.” Or he might rush down court and take his jumper before his teammates — particularly the big men – could cross the center line. And it got worse — much worse — before it got better. Mark Kriegel, in his fine Maravich biography, Pistol, describes an ugly scene midway through that difficult rookie season. Pete and his roommate Herb White arrived at the Hawks’ hotel between 3 and 4 in the morning:

Pete became embroiled in an argument outside, flinging his wallet at the cabbie who had dropped them off. Herbie was left to retrieve the billfold as Pete, impossibly loud and drunk, staggered toward the elevator. Herb figured the worst was over as the elevator doors opened on their floor, revealing (Hawks starting center) Walt Bellamy, all 6 feet 11 inches of him.

“Pete just snapped,” White recalls. He jumped on Bellamy’s back and started to rant. At first it sounded as if Pete were speaking in tongues. But then some of his words became decipherable. At first Herb couldn’t understand why he was saying what he was saying as Bells was the most laid-back guy on the team. And as crazy as he could be, the one craziness he didn’t suffer from was racism. White’s insight had arrived only over decades. He now understands that Pete has finally broken. The raving lunatic was strangely sane: His slurs were an incantation, a desperate, profane prayer for release. He wanted out.

“I hate you,” he screamed. “I hate all of you n…….”

Bellamy could have broken him in half. Instead, he just shook his head. The big man wore a look of recognition, resignation, and finally pity …

“Take this crazy motherfucker back to his room,” he said.

Blind Man Breakin’ Out Of A Trance … But as the season drew to a close, Maravich started delivering on his promise. He finished with a scoring average of over 22 points a game, and most remarkably, his defense improved as he gleaned the nuances of the pro game. The Hawks made the playoffs, and even better for team owner Tom Cousins, they made more money. According to The Wall Street Journal, gross revenues for the Hawks had jumped by 50 percent. Because of Maravich, Cousins would have his new downtown arena, the Omni. The riches were falling into more pockets than his, but Maravich sensed little redemption. He gave thought to walking away from basketball. “You don’t know what I’ve been through,” he said. “It’s not worth it.”

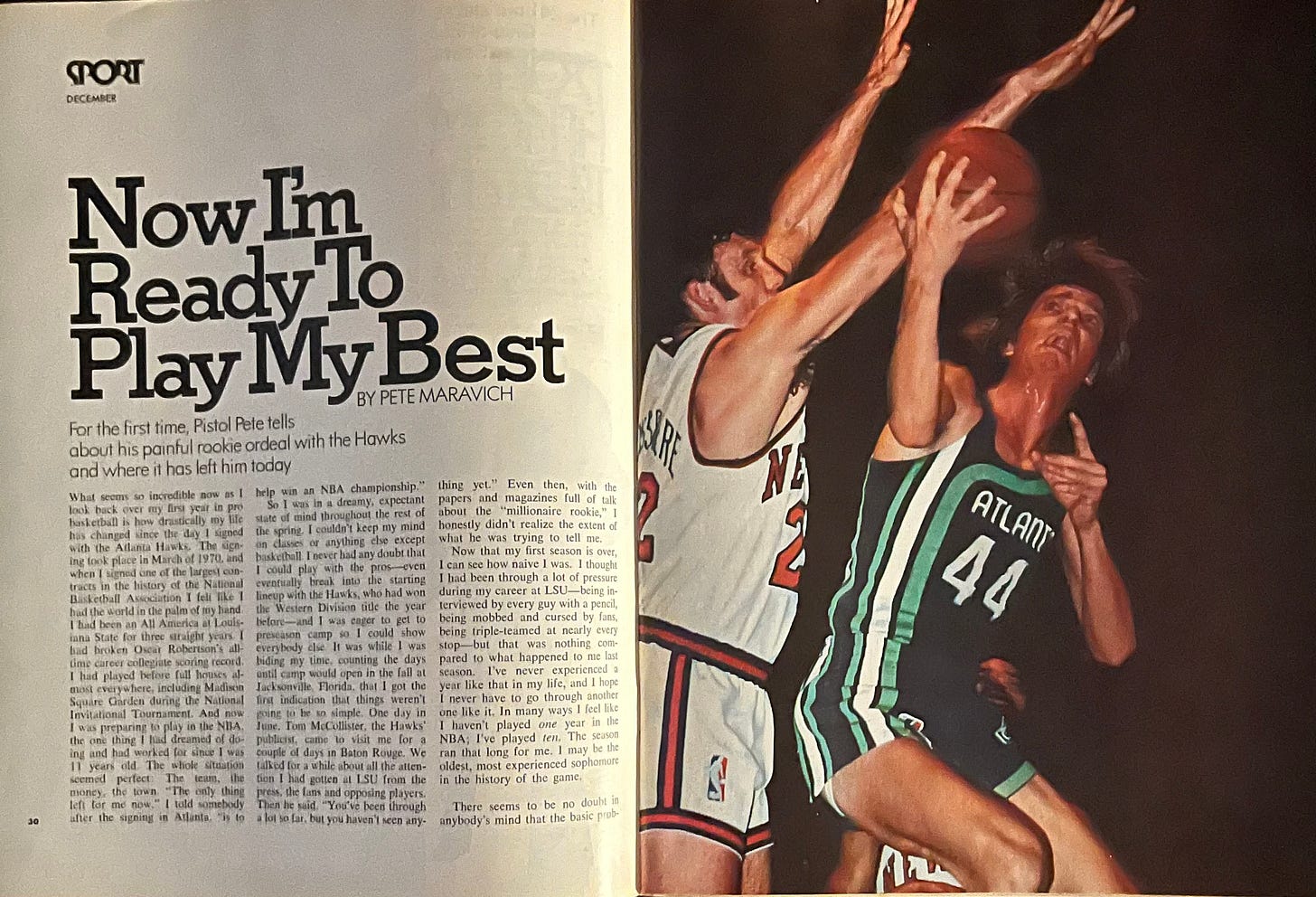

That comment wasn’t taken seriously. After all, it was imperative that Maravich stick with the game and prove how great he knew he was. An article under his byline entitled “Now I’m Ready To Play My Best” appeared in the December ’71 issue of Sport magazine. In the article, Pete acknowledged that all had not gone smoothly in his rookie year, but lessons were learned. “I may be the oldest, most experienced sophomore in the history of the game,” he wrote of his upcoming second season. “I think I’m ready, beginning with this year, to play my best basketball in the NBA. The shakedown is over.… All I really want to do is play basketball, and I hope everybody is going to let me do it.”

So Pete hung in there, persevering as an NBA player, yet troubled with the game of life. Over the next two years, there were bouts with mononucleosis and bells palsy, plus a harsh reprimand from a Florida judge after Maravich pleaded no contest to a drunk driving charge. Judge Silverman told him, “You can forget about alcohol, or if you continue, you will probably end your career around a telephone pole or become debilitated.”

In Pete’s third season as a pro, the Omni opened. The souvenir dedication book for the new facility, featured a commentary on the Hawks that surmised, “This should be the year that Maravich stands the NBA on its ear.” That didn’t happen, yet Maravich appeared in 79 games and finished with an average of 26 points per game, good for fifth in the NBA. While that didn’t stand the NBA on its ear, it appeared the education of Pete Maravich, professional basketball player, was taking hold.

The Atlanta Hawks got off to a snappy start in the ’73-74 season, and it was Maravich leading the way. Finally, more attention was paid to what Maravich did with a basketball. No longer was the focus on team jealousies, selfish play, public drunkenness or any of the other controversies. Even such silliness as Pete’s confession two years earlier to Hawks announcer Skip Carey that he believed in UFOs and extraterrestrial life forms could be brushed aside. What mattered was what Pete Maravich was doing on the court — and as astute followers of the game were discovering, few had done it as wondrously as Pistol Pete in his 4th season as a pro.

In his song, “Dignity,” Bob Dylan sings of the “Chilly wind sharp as a razor blade” and “House on fire, debts unpaid.” Those lines come to mind when recalling Pistol Pete’s early years. The pressure was always on as people felt he had let them down. But Maravich, now experienced in the ways of the pro game and the school of hard knocks, was observing life with more clarity, even as he obsessed over diets, beliefs and expectations. In his breakout ’73-74 season, he acknowledged fame and fortune wasn’t worth the stress. He spoke of retiring from the game after his contract expired. “I don’t want to play 10 years in the NBA and die of a heart attack at 40,” Maravich told a reporter. The search for meaning didn’t end on a basketball court. As Dylan would write 14 years later:

So many roads, so much at stake

So many dead ends, I’m at the edge of the lake

Sometimes I wonder what it’s gonna take

To find dignity

I’m On The Rollin’ River In A Jerkin’ Boat … Maravich could feel satisfaction with how he advanced as a player, but the Hawks ended the ’73-74 season with a record of 35 wins and 47 losses. Somehow that was his fault, despite injuries to key teammates. After all, he was no longer drawing the big crowds. In a game in mid-March ’74, Maravich scored 30 points but there were only 6,889 at the Omni to see the Hawks lose to Detroit. Atlantans had long exhibited fickle attitudes toward even the greatest athletes. The Atlanta Braves’ Hank Aaron, advancing toward baseball’s most heralded record, that of the 714 home runs hit by Babe Ruth, often noted Atlanta’s attention deficit. Late in the ’73 season, he hit home run number 711, but only 1,362 fans were at Atlanta Stadium that day. It was then the smallest crowd ever for a Braves game in Atlanta. Despite his achievements on the field and his distinguished manner off it, Aaron often felt Atlanta didn’t give a damn. And when the Braves shipped him to the Milwaukee Brewers in November ’74, just seven months after hitting that 715th home run, Atlanta seemed to care less. After all, Pete Maravich, once deemed a sporting savior for the city, was traded away too.

The Atlanta Hawks had become a financial drain for owner Tom Cousins, already struggling with the recession impacting his real estate business. Maravich had to go. The Hawks could start over with the draft choices they received for Maravich from the New Orleans Jazz, an expansion team just beginning its first season in October ’74. The trade was called “The Louisiana Purchase,” but all it brought Atlanta’s pro basketball fans was more misery. The Hawks blew the negotiations with their top choices the next year and found themselves nine games worse than the Jazz in Maravich’s second season in New Orleans.

Though Maravich would not lead the Jazz to greatness, he had fabulous moments during his five seasons in New Orleans, leading the NBA in scoring in the ’76-77 season. Bob Dylan once saw Maravich play in New Orleans. He wrote about the experience in his memoir, Chronicles:

He was something to see — mop of brown hair, floppy socks — the holy terror of the basketball world — high flyin’ — magician of the court. The night I saw him he dribbled the ball with his head, scored a behind the back, no look basket — dribbled the length of the court, threw the ball up off the glass and caught his own pass. He was fantastic. Scored something like 38 points. He could have played blind.

Maravich dazzled Dylan, as he had hundreds of thousands, but his singular talents weren’t enough for any of his teams to win an NBA championship. To be among the best left standing — and triumphant — is what Pete wanted most. He talked about it early in his career, and he did so especially in the ’79-80 season, when he played 26 games with the Boston Celtics. Joining a revitalized Celtics team, spurred on by the game’s latest Great White Hope, the rookie Larry Bird, Maravich could just see the championship ring on his finger. In an article for the April ’80 Inside Sports, David Halberstam, one of the 20th Century’s best journalists, wrote of how Maravich believed a world title could make up for all the misunderstanding, all the disappointments:

The fixation with the ring, which was genuine, was not just a fixation with a championship and a desire for professional bauble, but an awareness of what his career had not been. “A stepchild of the American imagination,” former teammate Rich Kelly once called him. Not a bad summation for a 10-year career, which did fire the American imagination, sell tickets, sell soft drinks, sell sneakers — and somehow failed more than it succeeded.

The Boston Celtics lost four games to one to the Philadelphia 76ers in the Eastern Conference finals in late April, about the same time Halberstam’s Maravich profile hit the newsstands. Only once in his nine previous NBA seasons had Maravich played on a team that won more games than it lost. His being traded to the Celtics by the Jazz, then having just moved to Salt Lake City, provided him with hope. The trade put him with a winner once more, but a Celtics championship, the team’s 14th, wouldn’t come for another year, with Maravich back home in Louisiana, trying to bring order to his life, albeit in a schismatic fashion.

Sick Man Lookin’ For The Doctor’s Cure … A quick study, Maravich had his wife, Jackie, teach him French. Now a father, Pete dedicated his energies to exposing his and Jackie’s first son, Jaeson, to whatever Pete thought would make the child stronger and smarter. There’d be much to absorb as Pete’s own search for insight and cultivation took him down many paths. In Pistol, Mark Kriegel describes the Maravich sojourn:

When Pete wasn’t gardening, fasting or conducting experiments in behavioral engineering, he spent good amounts of time reading up on reincarnation, betting the stock market, or megadosing on vitamins. He arranged for the purchase and transportation of drugs from East Germany said to have life-extending properties, “stuff from Europe that was going to help me live to be 150,” he would recall.

Meanwhile, he began planning for an apocalypse, albeit one of an unspecified nature. Spurred on by dedicated reading of the latest survivalist magazines, he bought thirty acres in Folsom, a secluded spread almost fifty miles away. He envisioned a solar-powered home with an underground bomb shelter.

Another son, Joshua, was born to him and Jackie in March ’82. Maravich had much to look upon with pride and much to live for but he often thought of ending it all. He’d tempt fate by climbing into his Porsche at night, putting pedal to the metal. One night, barely eight months after Joshua’ s birth, Pete went on another of his wild rides. Lucky enough to get back home, Pete gave thought to his life, particularly its toughest moments. Always crystal clear was the whirlwind of his youth, when his obsessive father helped guide him to athletic brilliance. There was a troubled older brother and his loving but fragile mother, Helen Maravich, who took her own life just eight years earlier. What Helen did was tragic, for her and those she left behind. Pete couldn’t do that to those depending on him. Wanting an answer then and there, he called out for God to save him. Maravich testified that he heard a voice “as clear as thunder” — right there in that room — calling out, “Be strong and lift thine own heart.” That was Pete’s Road to Damascus moment, and a conversion that made one think of the advice John Prine offered in his song, “Spanish Pipedream (Blow Up Your TV)”:

Blow up your TV, throw away your paper

Go to the country, build you a home

Plant a little garden, eat a lot of peaches

Try and find Jesus on your own

Pete may have never heard Prine’s song, but he had moved to the country, worked his garden and found Jesus on his own. Naturally, he had to tell others of his discovery. Jackie, raised in the Catholic Church, heard no voices “as clear as thunder” and was reluctant to attend Baptist services with Pete. However, his embrace of Jesus, as unconventional as it appeared, took hold of Maravich more than the other beliefs and philosophies he espoused previously. He impressed Jackie with his calm and loving manner. Something got a hold of Pete’s heart, and she joined him in the faith soon after, being baptized in a Kenner, Louisiana, church.

On Tuesday, January 5, 1988, Pete Maravich took part in a 4 on 4 game in the gym at the Church of the Nazarene in Pasadena, California. During a break, Pete was taking shots from the three point line. He said he felt great. Then a surge of weakness filled his body. His eyes rolled to the back of his head. Pete’s legs caved in and his head hit the floor. Friends on the court worked to revive Pete but nothing could be done. One of the friends, Ralph Drollinger, a center for the UCLA championship teams in ’73 and ’75, remembers, “I think he was dead the minute he hit the ground.” At the age of 40, Pete Maravich died of a heart defect, one that he was born with, unbeknownst to him or anyone else. Maravich was born without a left coronary artery to his heart. Working overtime, his right coronary had become greatly enlarged and it gave out, though later in life for Maravich than others with the same defect, as it usually kills its victims before they reach 20. Torn and frayed by his struggles, Pete’s heart took some hits, but it proved stronger than anyone could have expected. And when he hit the floor on that last day, his heart was at peace. And he knew it.

I Met The Sons Of Darkness And The Sons Of Light … The news of Pete’s death shocked Bob Dylan just as it did the millions of other basketball fans who remembered seeing Maravich running up and down the court, endlessly improvising on Dr. Naismith’s game. Memory becomes more selective as the years and decades pass, so we fixate on the Maravich moving so fast, passing so beautifully and making shots heretofore thought impossible. Talk about a guy, now gone for over 35 years, who remains forever young.

Bob Dylan was having coffee with his aunt when he heard of Maravich’s death. Reflecting again on Maravich in Chronicles, Dylan wrote:

Pistol Pete hadn’t played professionally for a while, and he was thought of as forgotten. I hadn’t forgotten about him, though. Some people seem to fade away but then when they are truly gone, it’s like they didn’t fade away at all.

Later that day, still down about Maravich, Dylan started and finished his song, “Dignity.” In Chronicles, he writes of the task at hand:

It’s like I saw the song up in front of me and overtook it, like I saw all the characters in this song and elected to cast my fortune with them. I have a problem sometimes remembering someone’s real name, so I give them another one, something that more accurately describes them, and I had a tendency to do that throughout this song. There were more verses with more individuals in different interplays. The Green Beret, The Sorceress, Virgin Mary, The Wrong Man, Big Ben and The Cripple and The Honkey. The list could be endless. All kinds of identifiable characters that found their way into the song but somehow didn’t survive. I heard the whole piece in my head — rhythm, tempo, melody line, the whole bit. I’d always be able to remember this song. The wind could never blow it through my head. This song was a good thing to have.

For sure, this song is a good thing to have. And there have been at least five Dylan recordings of “Dignity” officially released, though nearly six years went by after Dylan first recorded the song before any of the versions hit the market. One, with a swampy sound, was recorded in early ’89 during the sessions for his Oh Mercy album, but it didn’t make the cut. That one is the favorite of many; it surfaced for the first time on a 2007 Dylan box set. Also recorded during the Oh Mercy sessions in New Orleans was a gospel-styled version — quite reverential — and then one with a rockabilly feel. Both made their official debut on Dylan’s Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased, 1989-2006, the eighth volume in The Bootleg Series, released in 2008. The first official release of “Dignity” was on Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits, Volume 3, which made it to the stores the same week (November ’94) that Dylan recorded the song yet again, this time for his MTV Unplugged appearance.

The recording made before the MTV audience is similar to the Brendan O’Brien-produced version on Greatest Hits, Volume 3, except it’s far better. For the hits collection, O’Brien added guitars and organ to the rhythm section and Dylan’s vocal from the first recording. That seems a simple enough job of overdubbing, but the results are clumsy and awkward. Much of what O’Brien added to the mix comes across as bells and whistles. The electric guitar is hardly in the same conversation with the other instruments. It’s just loud, replete with Van Halen effects. The fascinating song bogs down. Thankfully, that’s not the case with the Unplugged recording. Bassist Tony Garnier and drummer Winston Watson energize and drive the Unplugged version, enabling the song to swing nimbly behind Dylan’s engaged vocals and O’Brien’s Hammond organ — seriously, O’Brien discovers his inner Matthew Fisher,* turning out riffs that serves as backdrop while highlighting the song’s melody. Everything works on the MTV recording of “Dignity.” The performance and the song itself measure up to how Webster’s defines dignity: The quality or condition of being esteemed, honored, or worthy. The definition also applies to how we remember Pete Maravich, very much on Dylan’s mind the day he wrote the song.

*Matthew Fisher was organist for Procol Harum on “Whiter Shade of Pale.”

A good read!

Stumbled here after watching ViceTV's Uninterrupted episode about Pistol Pete Maravich. Engaging, thoughtful, well-written piece. Thanks for sharing it here!