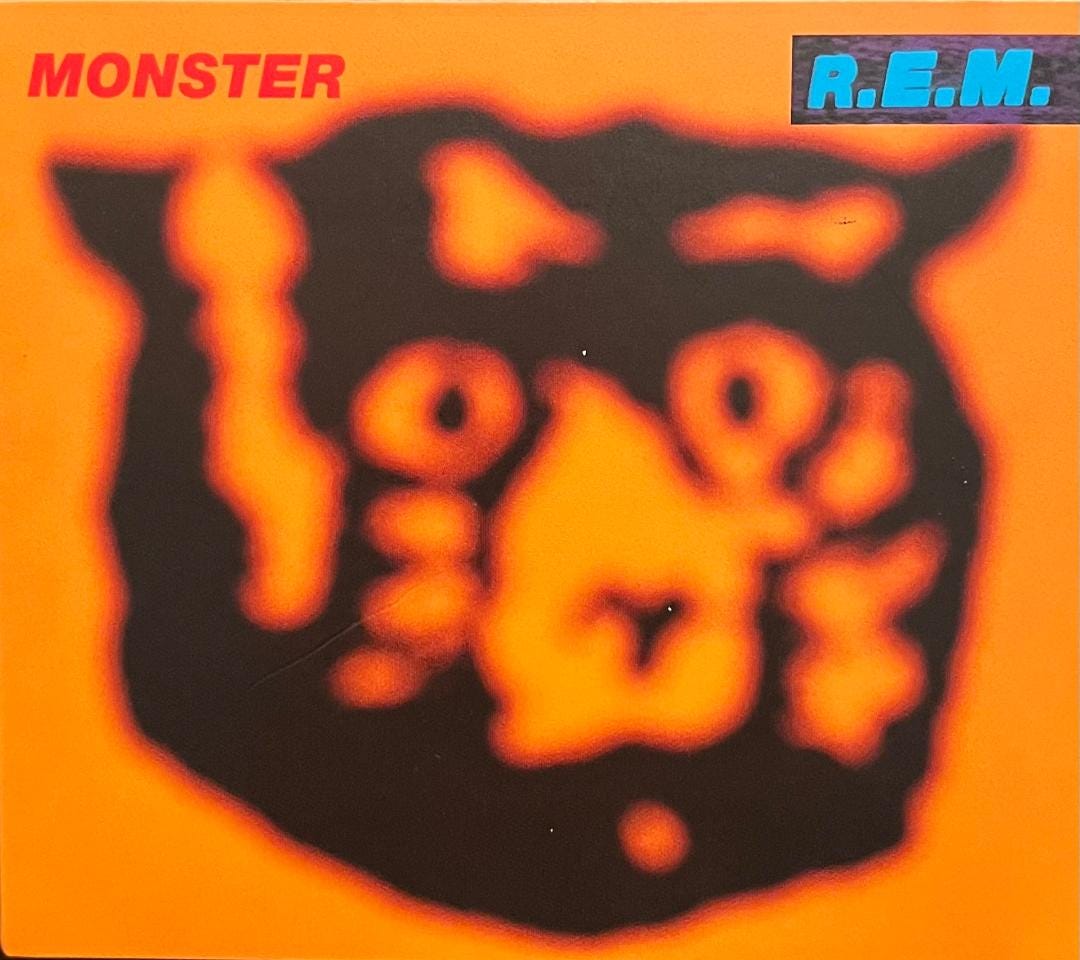

With the release of Monster, one very hard-rocking album, R.E.M. staked new ground. A departure from their two previous albums, Out Of Time and Automatic For The People, Monster debuted at No. 1 on the Billboard charts in Fall ’94. Monster had mischievous and dark qualities; it was a strapping presentation. The album sizzled with guitar distortion, feedback and crunch. Monster sounded defiant. Still, many of the songs were playful and engaging. R.E.M.’s melodious style remained intact.

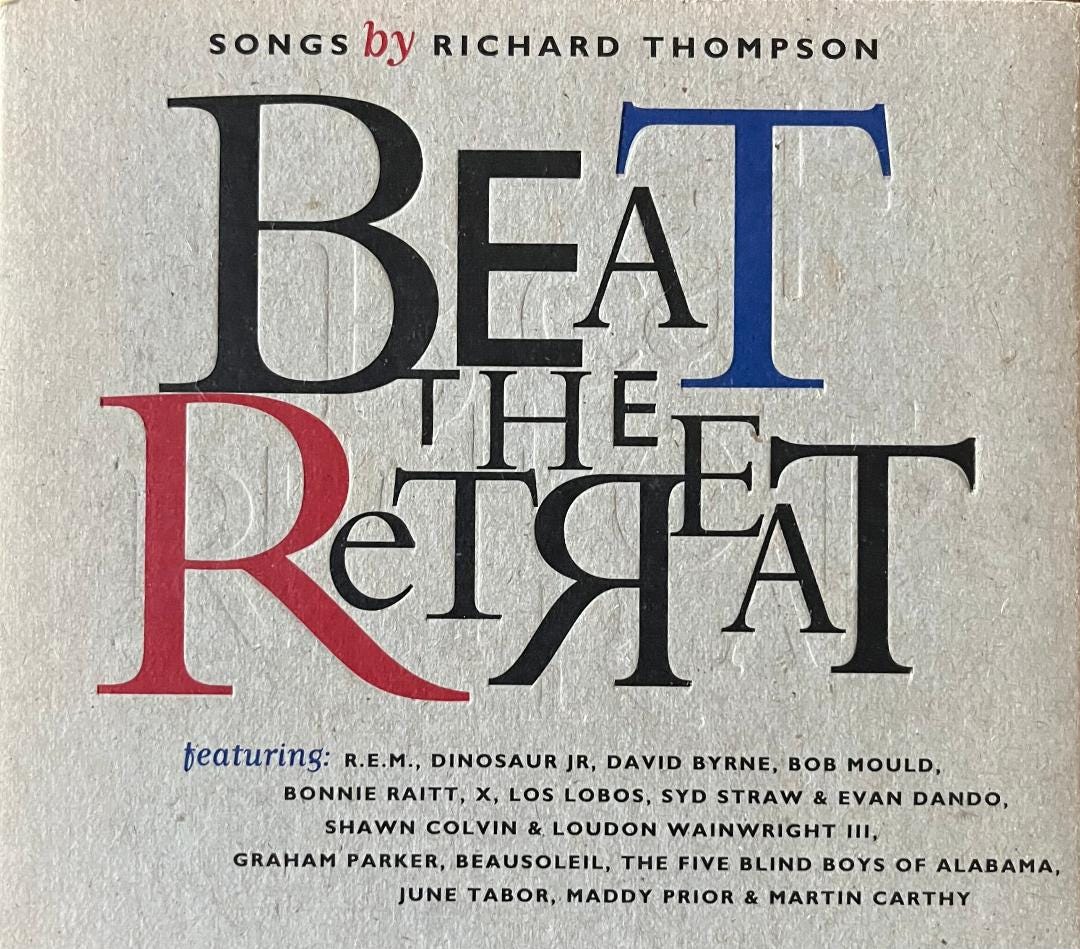

Again, less than a month later, R.E.M. displayed its flair for melody with a rendition of Richard Thompson’s “The Wall of Death.”

Included on the Thompson tribute album, Beat the Retreat, R.E.M.’s take on “The Wall of Death” reveals a contented spirit in a song that Rolling Stone once called “joyfully perverse.”

“The Wall of Death” by R.E.M. opens with a softly strumming guitar as Michael Stipe quietly sings, “Oh no, no, no, no, no….” Then the determination in the song’s message kicks in. Stipe’s vocals are gentle, but his mind is made up. The song’s protagonist knows his way around an amusement park. There are a lot of rides that might amuse, but offer little excitement. He’ll take his chances on the Wall of Death. Stipe relates to the protagonist. He sounds calm but resolute. It’s a bright vocal performance, especially when he harmonizes with bass guitarist Mike Mills.

Not since The Beatles has any band worked its way around melodies better than R.E.M. Their approach on this song, as with many of their other recordings, is Beatlesque, not just in its tastefulness or sound, but in the way the musicians connect with each other. Peter Buck’s lead guitar work is simple, resonating beautifully with a snappy pedal steel and electric piano. Bill Berry’s drumming is direct but understated, as is Mills’ bass-playing. It’s not their song, but “The Wall of Death” is a shining example of the precision and beauty R.E.M. has brought to the body of work they assembled over three decades.

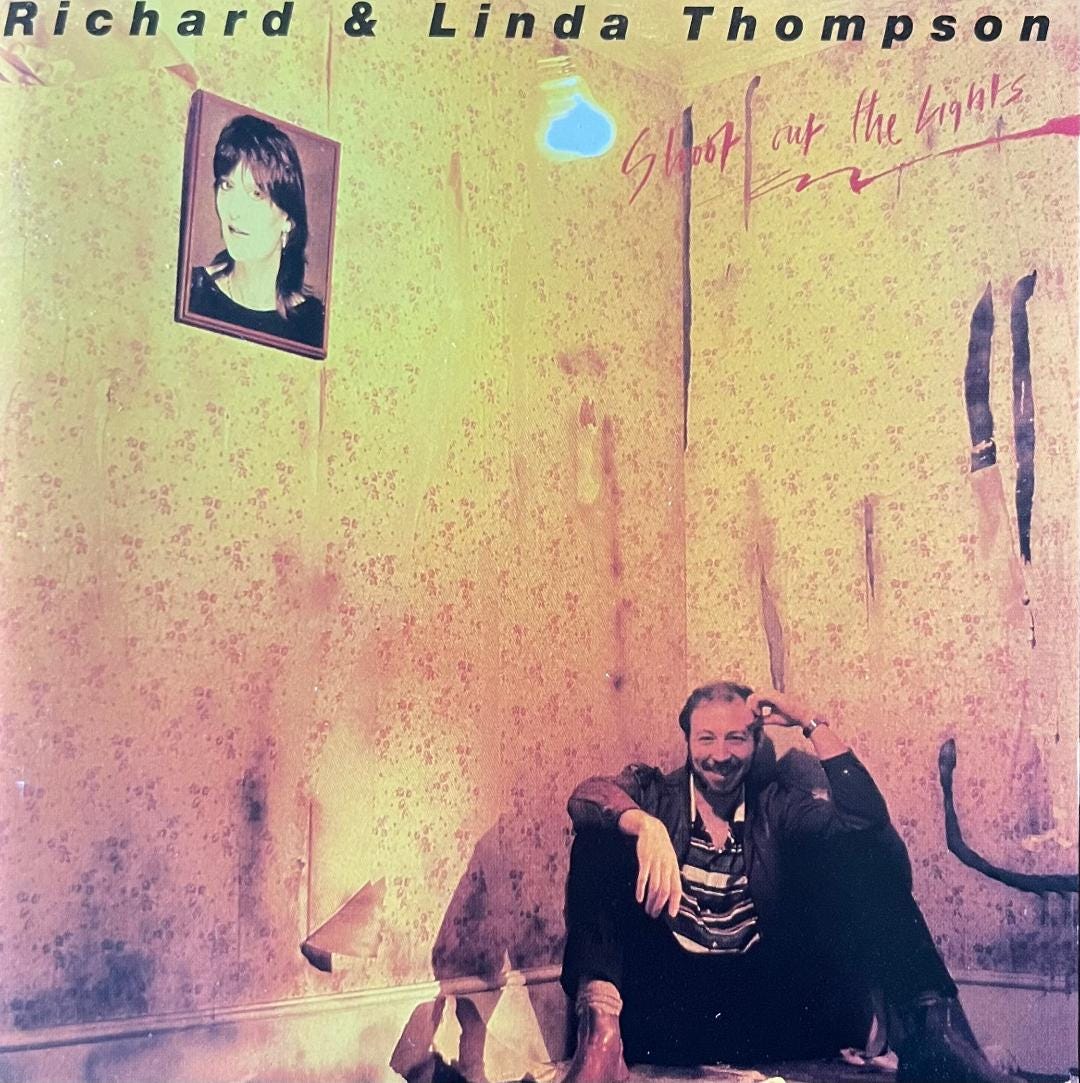

While R.E.M.’s pop sensibilities were evident on “The Wall of Death,” the original version recorded by Richard and Linda Thompson is more expressive. It’s a spellbinding song in the hands of the composer and his wife (at the time), and they deliver it intently, as if leading friends in a Scottish pub on the chorus. They approach the song’s declaration, joyfully or not, as a philosophy for living. Ideal for a pub setting; their vocals are stout. The same goes for the attitude Thompson has conjured. A world of risk and intrigue is favored over one with the comforts and predictability of an orderly life.

A life of mystery and a hope of fortune occur when breaking from the ordinary. Thompson declares riding “The Wall of Death is the nearest to being free.” He takes a dim view toward the rides (and a lifestyle) that offer a familiar outcome:

Well you’re going nowhere when you ride on the carousel

And maybe you’re strong, but what’s the use in ringing a bell

The switchback will make you crazy

Beware of the bearded lady

Oh, let me take my chances on The Wall of Death

“The Wall of Death” was one of the nine splendid songs included on 1982’s Shoot Out The Lights, the last album Richard and Linda Thompson recorded together. The break-up and its aftermath were stormy for the Thompsons. Richard took his chances, choosing to be with someone else, marrying Nancy Covey, an associate who helped him plan a concert tour of the USA. Linda, left behind with three children, was the victim of chances taken and made clear her bitterness. With the marriage finished, Richard and Linda still toured to support Shoot Out The Lights. Things got tense. Reportedly the tour included screaming matches with Linda hitting and tripping the wayward Richard at various venues.

As the years passed, Linda Thompson gained some perspective on the changes in their lives. She told the BBC’s Radio 2, “I think if Richard hadn’t gone, he would have imploded. He had lived too narrow for too long and I think he had to shed me and the kids to get out of it.” She did admit the break-up was painful but not as acrimonious as reported. Tensions eased, and in 2002, Linda released her second solo album, Fashionably Late, with her ex providing lead guitar and backing vocals on the opening track, “Dear Mary.”

In an interview with Rolling Stone in May ’02, tongue firmly in cheek, she spoke of her famous guest guitarist, “Richard is and was always a pleasure to work with. Plus he worked for free. I could love Stalin for that.”

Richard Thompson’s solo career took off quickly after the break-up. Not missing a beat, he has blazed an impressive trail, recording more than two dozen solo albums (studio and live) since 1983. Most have been critically acclaimed, although Thompson hasn’t experienced a big commercial breakthrough. As on the six studio albums he recorded with his ex-wife, the songs on his solo efforts are intense and alluring.

On the road and in the studio since 1967, Thompson, 18 that year, joined the folk-rock band Fairport Convention as their lead guitarist. His prowess on the guitar fascinated even in the early days. Among the fascinated was Joe Boyd, the legendary producer who has often worked with Thompson. In his book, White Bicycles, Making Music In The 1960’s, Boyd expressed his regard for Thompson the guitarist:

He can imitate any style, and often does, but is instinctively identifiable. In his playing, you can hear the evocation of the Scottish piper’s drone and the melody of the chanter as well as the echoes of Barney Kessel’s and James Burton’s guitars and Jerry Lee Lewis’s piano.

Boyd’s reference to the bagpipes brings to mind Thompson’s father, who was born in Scotland. The elder Thompson worked as a detective for Scotland Yard but devoted much of his leisure time to listening to jazz and Scottish music.

The music of Scotland goes beyond the bagpipes. Perhaps even more significant is the fiddle. It’s the Scottish fiddle that’s infused much of American roots music, particularly bluegrass. No less than “The Father of Bluegrass,” Bill Monroe, acknowledged the Scottish influence, describing bluegrass as “Scottish bagpipes and ole time fiddlin’. It’s Methodist and Holiness and Baptist. It’s blues and jazz, and it has a high lonesome sound. It’s plain music that tells a good story.”

Scotland has also contributed to the literary world through the works of novelist Robert Louis Stevenson and poet Robert Burns. The great tradition of the dramatic arts in Scotland has long been noted as well. In fact, the oldest theatre currently surviving in Scotland while serving its original purpose is the Dumfries Theatre Royal. It opened in 1792. Robert Burns provided funds for its construction.

More than 200 years later at The National Theatre of Scotland, a production was staged that would have amazed and likely confounded Robert Burns. The name of the production? The Wall of Death — A Way of Life.

Much controversy has ensued regarding The Wall of Death — A Way of Life. Is it really theater? Or simply showmanship? Joyce McMillan, in The Scotsman, writes that a company like the Ken Fox Troupe, the last family of Wall of Death riders, has something to teach about the art of performance and the risk it entails. In her 2/12/10 review of the production, she describes the awe-inspiring skills of the Fox team:

15 minutes of brilliant, searing showmanship from Fox and his young riders. Their poise, their calm, their perfect athleticism, as they drive their roaming bikes to the top of the vertical wall, soaring and swooping like dancers and acrobats, draws gasps of excitement from the audience gathered in a circle around the top of a great drum.

McMillan also took note of the debate over the National Theater of Scotland, its director, Vicky Featherstone, and what’s considered theater. McMillan writes that “we should welcome Featherstone’s efforts to explore and redefine the limits of the art form for new times.” Maybe Featherstone senses riding a wall of death offers the nearest chance to being free after all.

Perhaps the lyrics of R.E.M.’s “Finest Worksong,” from their ’87 album, Document, inspired Vicky Featherstone and others choosing to ride their own walls-of-death, whatever they might be. “Take your instinct by the reins,” Michael Stipe exhorts. That inclination has worked for many, Richard Thompson and the members of R.E.M. among them.

While a devoted REM fan, Thompson has always existed on the periphery for me. Thanks for helping me get more acquainted with him. Seems I may need to take a deeper dive. Meanwhile, I continue to find Monster abandoned by more fans than any other REM album, with multiple copies of the CD always peppering the used CD racks at local music stores. A shame, because it's a grand album.