Saying It Loud: James Brown on Defiance and Forgiveness

James Brown and the Men Who Would Be President, Part Two

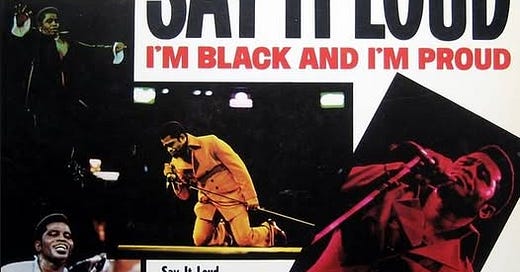

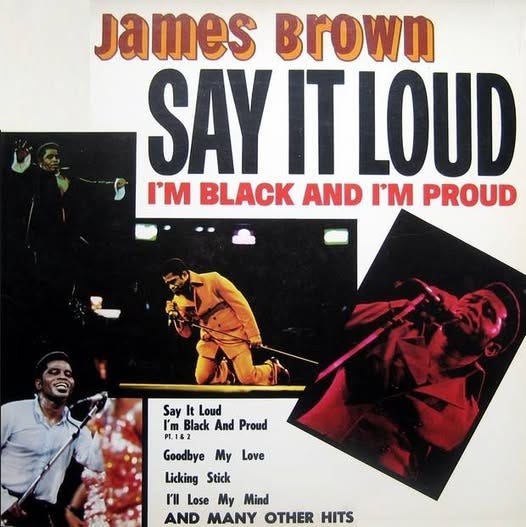

Early in the ’68-’69 school year, my junior high classmate Ruth Carter boldly decorated the front and back of her Blue Horse binder with the determined message of Soul Brother Number One: JAMES BROWN SAYS “SAY IT LOUD, I’M BLACK AND I’M PROUD!”

Only thirteen, Ruth carried herself proudly; a friendly and observant girl, wise beyond her years. She was among the first Black students to attend the previously all-white junior high school located in suburban Clayton County, just south of Atlanta. Nearly all of Georgia’s public schools, even in its capital city, took as much time integrating as “all deliberate speed” allowed.

Ruth and her fellow Black students, mostly from Rosetown, a Black community in Forest Park, became fast favorites with many of us. Now, why was it that politicians and community “leaders” didn’t want Black students attending our schools? Were they afraid of what we might learn? Because of Ruth and our other new friends from Rosetown, I learned more about James Brown, a dynamic and intriguing performer whose bold and pulsating songs struck fear into the hearts of white parents in my town. There the N-word was tossed about freely, in the schools, churches, and coffee shops, whether discussing the upcoming elections or what was wrong with the Atlanta Falcons. With more young white teens in suburbia coming to admire a self-assured Black man like James Brown, the world could change. Attitudes could change. The way-it-had-always-been would be questioned.

So let there be no doubt that parents would be alarmed if their kids happened to turn the radio dial and hear James Brown utter these words:

Looky here

Some people say we got a lot of malice

Some say it's a lotta nerve

But I say we won't quit moving

Until we get what we deserve

We've been 'buked and we've been scorned

We've been treated bad, talked about

As sure as you're born

But just as sure as it take two eyes to make a pair, huh

Brother, we can't quit until we get our share

And that was just the first verse. Then keep in mind the title was repeated at least two dozen times.

But James Brown didn’t worry over some Bob Ewell-type being offended by the positive messages in his songs. After all, important people, even those wanting to be President of the United States, came to James Brown for help and advice. To paraphrase Bob Dylan, he was beyond the command of any Bob Ewell.*

Three months before the August '68 release of “Say It Loud - I’m Black and I’m Proud,” Brown spoke with President Lyndon Johnson at a White House dinner, where he also spent time cutting up and then talking seriously with Vice President Hubert Humphrey, a good friend. Johnson had decided against running for a second full term in the Oval Office, whereas Humphrey had just thrown his hat into the ring. Close friendship or not, Brown had already reached out to Robert F. Kennedy’s campaign privately to confirm he would endorse Kennedy for the presidency in the month ahead, upon returning from Vietnam, where he performed for the troops. Brown would meet up with Kennedy campaign officials to set up the announcement. Tragically, the meeting never took place as Kennedy was felled by an assassin’s bullet on June 5, just hours after winning the California Democratic Primary, which put RFK in the driver’s seat for his party’s nomination in August. The last words Kennedy uttered before the shooting were “Now it’s on to Chicago and let’s win there.” He knew there was still lots of work to do. Humphrey and Senator Eugene McCarthy served as strong competition as the convention neared, but he and his campaign were up for it. What the party and the nation were not up for however, especially two months after the murder of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., was political violence thwarting the will of the people.

Like McCarthy, Kennedy (RFK) was strongly against America’s involvement in the Vietnam War, but he connected with voters on many more issues. His ascendency as party frontrunner was at times breathtaking. Humphrey embraced what he called the “politics of joy” whereas RFK ably communicated a renewed American vision recalling his late brother’s short-lived presidency, which also ended violently. RFK’s supporters thought he could deliver America from its spate of violence and the coarsening spirit directed at its Black citizens, so apparent in the campaign of another presidential candidate, Alabama Governor George Wallace, who was seriously courting the Bob Ewell* vote.

In 1964, during his first presidential campaign, Wallace thought there might be some Bob Ewells among the Atticus Finches in northern towns such as Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Given that his “segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” assertion went over so well in the Deep South’s conservative Christian community, he sought audiences before religious groups in Wisconsin just ahead of the state’s presidential primary. In his book, George Wallace American Populist, Stephen Lesher reported that while most of the church groups wanted nothing to do with him, a ministerial association in Oshkosh invited him to discuss his views, despite his twisted takes on God, race, and brotherhood. Before numerous audiences, Wallace previously had gotten away with such drivel as this:

“I am no racist. I believe there is a God and he loves all men, and if I hate a creature God made because of their color, that is evil. But I am a segregationist because I believe that segregation of the races is best for both peoples.”

At the Oshkosh meeting, Ray Heilborn, a Methodist minister, went beyond seeking a dialogue with Wallace. He conveyed empathy with Wallace’s approach, given that he himself opposed racial integration. A spiritual leader of the predominantly white city put it to the governor this way:

“We’re a bunch of Northerners whistling ‘Dixie.’ We don’t have any Negroes here at all and we are all scared to death that we might get some and not know what to do with them.”

Several ministers, embarrassed by Heilborn’s comments, returned to the issue at hand: Wallace’s continued treatment of Alabama Blacks as second-class citizens, with no regard to their “basic human rights.” Shameless, but quick on his feet, Wallace responded, “You all might spend a little less time worrying about Negroes in Alabama and a little more worrying about the Indians in Wisconsin and the conditions they live in on reservations.” It was classic whataboutism, demonstrated some 45 years before the term was conjured. Wallace was correct in his assessment of Native Americans on Wisconsin reservations but was wrong in ignoring questions about the treatment of Blacks in Alabama. Yet, the small meeting in Oshkosh was beneficial for Wallace, with the newspapers picking up his Indian reservations comment. It brought him the support of most Native American voters in Wisconsin, where overall, he picked up a third of the votes in the Democratic Primary.

Back in Wallace’s Deep South, one of its most successful native sons, James Brown, didn’t see things as Wallace did. In fact, just weeks after the Wisconsin Primary, Brown recorded “Out of Sight,” which caught the interest of the white pop audience. It went to #24 on the Billboard Hot 100 in summer '64, a time of great expansion for the pop music scene. Beatlemania was at a peak, with other British bands besides The Beatles climbing the charts. Motown, the Black-owned label out of Detroit, captivated white audiences with such great acts as the Supremes, the Temptations, and Marvin Gaye. A world of discovery was at work. The white kids were buying R&B and Soul records, bringing Black music into their homes for the first time. Brown recognized this, just as he had seen that whites were attending his concerts up North. He wanted all the kids, Black and white, grooving together at his concerts in the South as well. Especially at Bell Auditorium in his hometown of Augusta, Georgia.

In 1961, a promoter booked Ray Charles for a concert at Bell Auditorium. The year before, he hit number one on the pop charts with the Hoagy Carmichael classic, “Georgia On My Mind.” But that didn’t mean Charles could perform before an integrated audience in Augusta. It was either play before an audience separated by race or don’t play at all. Charles took his piano and went home. But James Brown was already home. He wanted to play for the homefolks without the city imposing its will on who sits where. In The Godfather of Soul, he vented on the foolishness of it all:

I wasn’t heavy into the human rights thing yet, but I knew I didn’t want to play a segregated concert in my own hometown, especially after the crowd had integrated itself when I played Jennings Stadium, the baseball park there. When I had played it a few years before, the audience had been segregated, as usual, but during the show the white kids started coming down toward the stage. Before long there were white kids and black kids crowding around the stage, dancing and hollering and having a good time. They had integrated themselves. I didn’t want to turn right around and let 'em be resegregated. I had grown up with the signs that read “White Drinking Water” and “Colored Drinking Water,” and it always seemed to me that water didn’t have any color.

Just as sure as water had no color, the authorities in Augusta, as well as the ones in Macon, Georgia, weren’t backing down on their segregation mandates. In 1964, even as President Johnson was working Congress to pass a civil rights law that would prohibit racial segregation in public accommodations, Brown’s concerts in the two towns he loved most were still officially segregated. However, Brown came up with a creative way for Black and white attendees to enter the venue, then take their seats and find people of a different race on the same row, maybe in the next seat. De Facto Integration. By mid-summer '64, Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act into law. Segregated seating at concerts were becoming a thing of the past. Out of sight!

Brown hated racism and its partner-in-hatred, segregation. It went against his sense of dignity. It went against what he was due as an American. It hurt him in the pocketbook. He certainly hated what George Wallace stood for, yet he would have enjoyed matching wits with the morally corrupt and — at times—erudite politician.

Eventually Wallace and Brown met, not as social and political adversaries, but as friends. In his 2005 memoir, I Feel Good, noting that he and former Georgia governor Lester Maddox, a lifelong segregationist, had become friends, Brown mused on Wallace:

“… He started off full of anger and hate for the Black man. Remember the “Segregation before, segregation now, segregation forever!” speech he made? He, too, became another of my best friends. He used to call me Brother Brown, and that always put a smile on my face. One day toward the end of his life, he took me aside and said, “Brother Brown, if I had known the things I know now about Black people, I would have never said all the bad things about them that I did.”

Brown believed Wallace’s apology was sincere, and it was more casual than those he he made to Alabama Blacks whose lives he damaged in more than two decades as governor. In 1979, likely before his personal confession to Brown, he appeared — unannounced — at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery to acknowledge his past, the wreckage he left behind, and the shame he felt. Paralyzed since a 1972 assassination attempt, Wallace spoke briefly to the congregation:

“I have learned what suffering means. In a way that was impossible (before he was shot), I think I can understand something of the pain Black people have come to endure. I know I contributed to that pain and I can only ask your forgiveness.”

That was impressive. Wallace’s apology was genuine, and even with the damage he caused (and the effects still linger), forgiveness is vital, for those confessing and those victimized by the confessor. But forgiving is not forgetting. One’s heart can influence how to feel toward a repentant sinner, but one’s mind remembers the evil the sinner has committed. Open the door to friendship but keep a close eye on the chastened friend.

However, journalist Josh Moon of Alabama Political Reporter, when considering society as a whole, didn’t promote such a benevolent attitude when Auburn University announced in 2020 it would remove Wallace’s name from a campus building.** Moon favored the removal, stating there was no redemption for George Wallace. In his column, published on June 12, 2020, he offered a quick perspective on Wallace and why he shouldn’t be honored:

Wallace wasn’t an ignorant racist. He knew better. He knew what was right. He knew what was decent. He knew that Black Alabamians were suffering and mistreated.

You see, Wallace was widely regarded, prior to his rise to the governor’s mansion, as a progressive thinker. As a judge in Alabama, he treated Black citizens with respect and dignity, going so far as to refer to Black attorneys as “Mister.”

Prior to his first run for governor in 1958, Wallace spoke out against the KKK and he received the endorsement of the NAACP.

He got crushed by John Patterson — — an outspoken and ignorant racist who happily accepted the Klan’s endorsement and promised to make sure black Alabamians never received fair treatment.

It was after that loss that Wallace famously said, “I was out-ni—-ed by John Patterson. And I’ll tell you here and now that I’ll never be out-ni—-ed again.”

And with that, George Wallace became the most racist governor in the nation for a period of time. There was no cause, no legislation, no movement that would help Black Alabamians that Wallace wouldn’t oppose.

Not because he believed in those causes or felt he was doing the right thing for the people. But because being a full-fledged racist won him votes, got him elected, and launched his campaign for the presidency.

On the day Wallace visited the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, his presidential aspirations were long gone. He appeared content to serve one more term as Alabama’s governor. (Wallace won a fourth non-consecutive four-year term in '83, winning the support of Alabama Black voters.) After that final term in office, he still had nearly a dozen years to live, albeit in great physical pain and surely, immense emotional sorrow as he looked back at years gone by — like 1964, when a different way of looking at the world and its people could have changed his life and the lives of the people in it.

Never within reach of the Democratic Party’s nomination in '64, Wallace, four years later, again ran for the presidency, this time as the candidate of the American Independent Party. Few gave Wallace any chance to win in a 3-person presidential race. Wallace also realized he couldn’t win, but thought he might win enough electoral votes in order to strike a deal with one of the two other candidates that would give the southern states more leeway on the matter of segregation. But Wallace’s support was too narrow and concentrated to enable him to make any deals. He won 46 electoral votes, gained by winning six states in the Deep South, where diehard whites held tight to their old ways and where young Black people chanted “I’m Black and I’m Proud” the loudest. Freedom, like redemption, was still a ways off.

*Bob Ewell is the vile racist character in To Kill A Mockingbird, the antithesis of Atticus Finch.

**As it turned out, Wallace’s name was not removed from the building at Auburn University, but it was removed from a building at the University of Alabama in 2021.

Also:

James Brown and the Men Who Would Be President, Part One

The Godfather of Soul was not a constitutionally-created position, but James Brown was still allowed to walk the corridors of power. Most of the presidents, from the 36th (Lyndon Johnson) to the 43rd (George W. Bush), had a connection with Brown, getting advice from him, whether they wanted it or not.