Sex, Lies, The Bee Gees, and The Beatles

The Bee Gees Equate The Beatles? Slow Down, You're Movin' Way Too Fast

Author’s Note: John Lennon liked the Bee Gees. He did so particularly in the early going, when the Bee Gees seemed just another band trying to emulate The Beatles’ sound. In a 1977 interview with Frank Rose, Maurice Gibb remembered the easy going friendship he developed with Lennon in the mid ’60s. Then there was Al Coury. In the late ’70s he was President of RSO Records, for whom the Bee Gees recorded. Previously, Coury had been with Capitol Records, where he was closely involved with the Beatles, before and after their break-up. He was especially instrumental in the promotion of solo albums by Lennon, as well as those by Paul McCartney. But then came the opportunity to run RSO. There is so much movement in the music business, with the business taking precedence over the music. And when it comes to friendship, well, that shouldn’t stand in the way of business. Or so it’s been said. Maurice Gibb declared “nobody ever matched the Beatles.” How true. But less than two years later, people working on behalf of RSO were manipulating the numbers to see that the Bee Gees “matched” The Beatles. Sadly, too many believe they did.

“Mediocrity transcends racial barriers.”

So said Brent Sorkin, wise man of the jazz department at the Atlanta Peaches Records and Tapes. It was early fall, 1975. Nearly a dozen Peaches employees were in the store’s back room, waiting for a staff meeting to begin. A familiar debate ensued. It concerned disco music, which most of us considered an unwelcome guest in the world of music as we defined it. Brent Sorkin’s response was to the claim that those who abhorred disco were being racist. In the debate, disco, even with its many white artists and fans, was considered by some as Black music, and for the people making that case, it was the Black music that mattered most. Everything before disco struck them as ancient and irrelevant. That riled Sorkin most of all. The music he loved and promoted was written and performed by Black Americans. He extolled the works of John Coltrane, Dizzy Gillespie, Oscar Peterson, and especially Miles Davis. Hardly anyone advocated, besides the journalist Ralph J. Gleason, for an artist as Sorkin did for Miles Davis.

Those of us schooled in 60s rock and soul dismissed the racist accusations as well. “C’mon over to my place and see the albums by Al Green, James Brown, Otis Redding, and Aretha” was the incensed reply when one’s perspective on music as related to race was questioned. And besides, as Sorkin stated, mediocrity transcends racial barriers. Just think of these two words: Barry and Manilow.

The steady creep of disco became quite discernible in ’74. “Rock the Boat” by the Hues Corporation, “Rock Your Baby” by George McCrae, “Kung Fu Fighting” by Carl Douglas and “Love’s Theme” by Barry White’s Love Unlimited Orchestra all seemed omnipresent. The soul music and rock and roll that had dominated the airwaves were taking back seats to a spin-off musical genre that struck fans of the Beatles, Dylan and Stax-Volt artists as tacky, insipid, and indicative of a consumerist lifestyle prevalent just five years after Woodstock.

Disco came off as a dumbed-down musical contrivance. Bethann Hardison, a Black runway model in the 70s, claimed disco was “created so that white people could dance.” Simple beats or not, some white rockers chose to remain wallflowers. They also noted that much of what passed for rock music was hardly edifying. Admirers of Buffalo Springfield, the Allman Brothers Band, and Bruce Springsteen, for example, gave no quarter to the heavy metal bands that were sprouting like kudzu. Rock aficionados who approached their music as Brent Sorkin did jazz scorned much of what could be found in a store’s Rock Department. As a high school friend once said, “I’d be embarrassed if my parents walked in and caught me listening to a Grand Funk Railroad album. I couldn’t defend it.” No kidding. “I’m your captain, yeah, yeah. yeah. yeah…” was no more inspiring than “That’s the way, uh-huh, uh-huh, I like it, uh-huh, uh-huh.”

The employees at Peaches Atlanta, Black and white, had disagreements over matters, but had genuine fondness for each other. The silliest disco songs (and there were many that qualified; start with “Blow Your Whistle.”) weren’t championed by any employee, just handed to customers possessing no shame. There was no shame on our part either. Peaches Atlanta needed the money. Business was still very good, but it wasn’t Fat City anymore. In a very short time a local competitor, Turtles Records and Tapes, went from two small stores, in what was-then the distant suburbs, to several locations, mostly located along I-285, Atlanta’s perimeter highway. That enabled young suburbanites to pick up the latest by Pablo Cruise or John Denver after dropping off their shirts at the cleaners next door. Turtles obviously couldn’t match Peaches for service, selection and environment, but they were competitive on pricing where most of Metro Atlanta’s whites were living. For them, a trip to Peaches was fun, but it was destination shopping and for many of those making the trip, the thrill was gone.

Peaches Records and Tapes also needed money to fund its national expansion and support its ever-growing corporate structure, with a lot of cash going to no good end. The beast had to be fed.

The work that was so much fun was starting to feel like real work. Maintaining and growing the business became a real concern. Then a Peaches store manager was quoted in a local newspaper saying Peaches wasn’t interested in appealing to the disco crowd. That was read between the lines as being hostile to Atlanta’s booming gay market. What was he thinking? Peaches was a full-line record store. We endeavored to carry everything available in every category. If someone anywhere in or near Atlanta wanted to buy a record, we wanted the record to be bought at Peaches. Sure, we’d rather sell a hundred copies a week of Dylan’s Desire than the latest by the Ohio Players or Bette Midler, but at the end of the day we wanted jobs to come back to the next day. Besides, our store was a place where everyone was made to feel comfortable and where the customers would join in the employees’ fun.

Frequently joining in the fun was Atlanta Mayor Maynard Jackson, likely to spend a c-note or two. Jackson, Atlanta’s first Black mayor, was great company to be around and the quintessential politician. He spoke to people, those he had never seen before, like he had known them a long time. “It’s good to see you,” Jackson would say in an easy, familiar tone. He’d talk politics, clothing (Jackson had lost a lot of weight recently and was having his elegant suits re-sized), and music. He’d first walk down the R&B aisle, spend a few minutes there, then ease through the jazz department before devoting most of his time to the classical selection. He’d carry a stack of albums with him to the register where he was given a new Peaches T-Shirt, a size smaller than the one he received the time before.

Another Peaches customer was former Georgia Governor Lester Maddox, best-known for his opposition to integration. We didn’t like his politics, but Maddox was a customer and treated kindly. A very courteous soul, Kevin Johnston, spent a half hour helping Maddox with some lively patriotic selections. As was Mayor Jackson, Maddox was gracious to everyone. We would have enjoyed his visit more, however, if he’d spent half as much as Jackson did.

Music Is A World Within Itself … In late ’76, the store’s two biggest selling albums were Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life, and Spirit by Earth Wind and Fire (EWF). Both albums were released in September ’76 and were often bought together by Black customers just as Frampton Comes Alive and Fleetwood Mac were purchased at the same time by thousands of whites earlier that year. Recalling what Sorkin said about mediocrity, one realized racial barriers were also transcended when excellence was involved: Scores of young white people from all over Metro Atlanta came to Peaches and bought Songs in the Key of Life.

(The Bee Gees meet with Polygram employees in Miami, 1982. L-R, Robin Gibb, Charmelle Gambill, Barry Gibb, Larry Hensley, Tracey Neilly, and Maurice Gibb)

While we were working to keep the bins filled with the new Wonder and EWF albums, Children of the World by the Bee Gees was released on RSO. It included the number one single, “You Should Be Dancing,” which had many longtime Bee Gees fans shaking their heads. The Bee Gees, long favored for their tight harmonies and Beatlesque melodies, were naturally accused of selling out. However, it was more likely the Bee Gees were looking to build a new audience as they were no longer considered important by the rock audience. Only one of their albums, Odessa, a two-record set from ’69 with an interesting back story, received and maintained high praise from critics. With most of their other albums, a considerable amount of tone-arm lifting was called for.

So the rock cognoscenti deemed the Bee Gees a singles band, yet a very good singles band, particularly in the late 60s and early 70s. Their most captivating single and still their one song that compels utmost attention is “Lonely Days,” released in late ’70. On this song, the Bee Gees went beyond sounding Beatlesque; they really sounded like the Beatles. Elements of several Beatles songs, especially those from the second side of Abbey Road, were adroitly used on “Lonely Days.” Within the last 30-40 seconds of the song, when Barry Gibb, voice filtered, cries out, “Lonely days, lonely nights, where would I be without my woman…,” he sounds just like John Lennon in the most exultant moments of “Instant Karma.” On “Lonely Days,” the music is beautiful and engaging; the words are spare and dreamy. The Bee Gees created an original work heavily influenced by a band long at the top of their game. The Beatlesque group produced one of the best Beatles tributes ever. And despite the chart success the Bee Gees would achieve in the late 70s, they hit their artistic peak with “Lonely Days.”

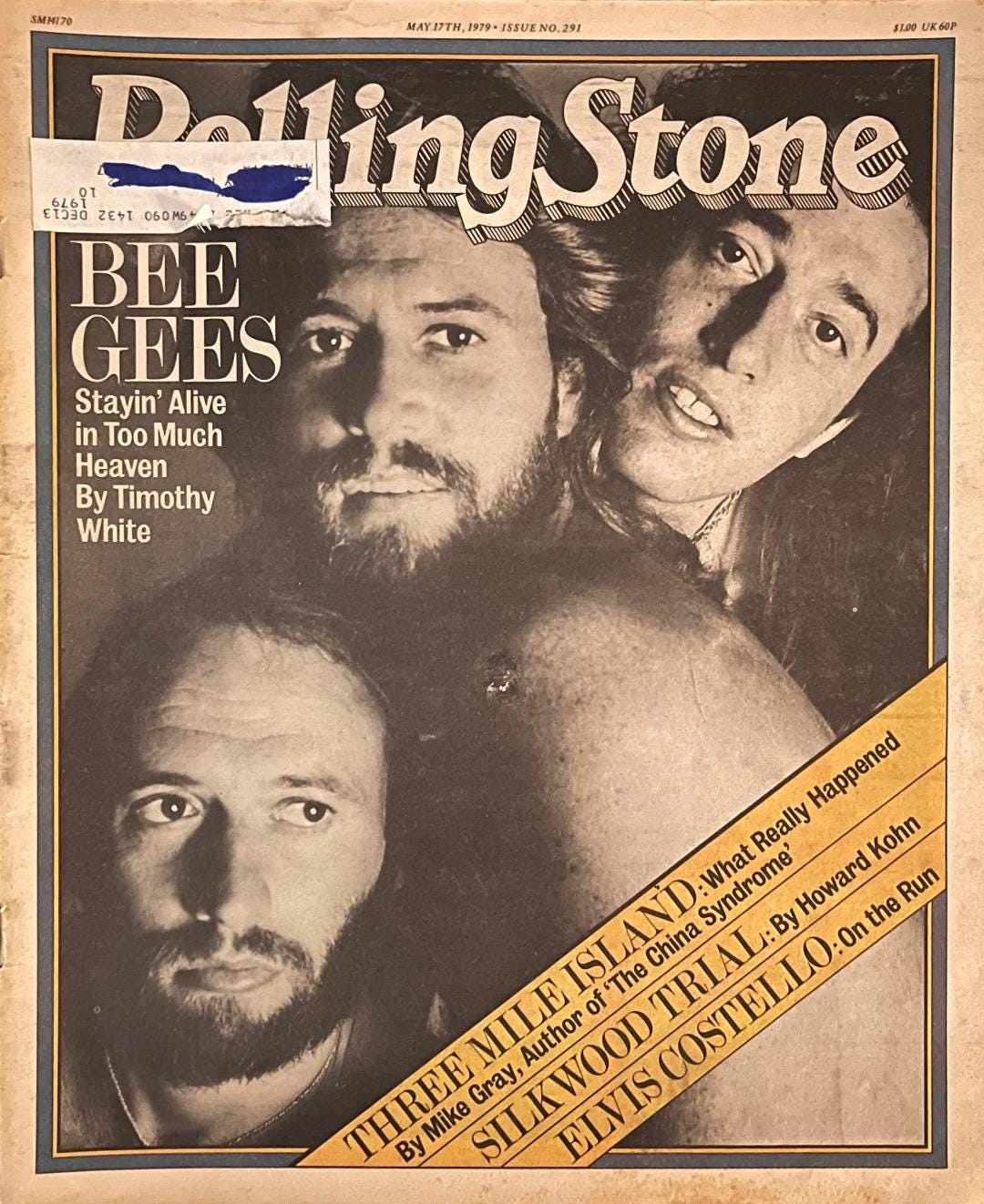

It’s Just Your Jive Talkin’ … Artistic peaks were hardly first and foremost on the minds of the brain trust at RSO Records. They cared most about the Bee Gees as a hit machine. From spring ’75 through spring ’79, the hits — big hits — kept coming. “Jive Talking.” “Nights on Broadway.” “Fanny.” “You Should Be Dancing.” “Love So Right.” “How Deep Is Your Love.” “Stayin’ Alive.” “Night Fever.” “Too Much Heaven.” “Tragedy.” “Love You Inside Out.” Eight of these songs made it to the top of the U.S. charts. The last six were credited with making it to number one, allowing the Bee Gees to tie The Beatles’ record for having the most consecutive number one singles in the United States. No doubt, as honored as the Bee Gees must have felt, it was the people at RSO and its distributor, Polygram, who wanted, craved and lusted after that record. To get it, intimidation and threats were in order.

Since 1936, Billboard magazine has published charts on the popularity of records played over the air and sold in the stores. Other trade publications, such as Cashbox and Record World, provided similar information but without Billboard’s dash and flair. Billboard had the panache and respect. If a record made it to number one on the Billboard Hot 100, then it most surely had to be the number one record in the U.S. But maybe not. Since Billboard staffers would gather its sales reports from radio stations, distributors and record stores across the nation, there were a lot of people involved, hence plenty of room for manipulation by the record companies. Said record companies who sought favor from the stores by getting them to buy their products would also lean, gently or not-so gently, upon its customers to report favorably on their current releases to radio stations and the trades. At Peaches, we found the reporting process to be a pain. There were a lot of calls from radio music directors and staffers at the trades who’d call out the names of countless records and then have us grade how well they were selling. It was arduous and time consuming. After all, our principal responsibilities were to get the records on the sales floor and into the hands of our customers.

Also, a pain with the reporting process was dealing with the record company promo guys who’d request – and at times – demand their records be given favorable reports, be they legitimate or not. In early ’77, I was named the singles buyer at Peaches Atlanta. Even though I had been in and around the business for nearly five years, I had no idea how important that position was deemed by certain people with certain record companies. Early on in my new role, CBS Records was really pushing the single “Dancin’ Man” by a group called Q, from Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, birthplace of both Papa John Creach and Joe Namath. The Epic promo guys would call or stop by the store to talk up “Dancin’ Man.” When I told them sales of the record were picking up, they were ecstatic. They asked if I would tell that to Rhett Walker, the Music Director at WQXI. Well, sure. The record was actually selling; reporting that would be the right thing to do. CBS pushed it really hard, all the way to number 23 on the Billboard Hot 100, not bad for a band no one had heard of before and would hear next to nothing from in the future. Q joined the hundreds of one-hit wonders that are referenced in trivia games.

When “Dancin’ Man” was added to the WQXI playlist, the CBS guys conveyed their gratitude. Gifts with my name on them arrived at the store. First, a very nice fruit basket. Then, a bottle of Chivas Regal. Nice gifts, but not such a nice feeling. Getting paid off for telling the truth.

The push behind “Dancin’ Man,” an easily forgettable song, was unusual for the guys at the CBS Atlanta branch. Bruce Sullivan, the CBS Salesman who called on our store, respected our enthusiasm for music and quite often joined our lively debates. Sullivan knew we didn’t care for the corporate line, and to his credit, likely ignored any instructions from above to pressure us on sales reports. The same could be said for the salespeople at the Atlanta branch of Warner-Elektra-Atlantic (WEA). The WEA guys understood what made business relationships genuine. The music they were selling was genuine; they had records by Warren Zevon, Talking Heads, Neil Young, and Ashford and Simpson to get in the stores. Conducting business genuinely was a no-brainer.

Still there were numerous people in the business playing games or cheating at the games. One afternoon when dropping off ad copy at a radio station, I was talking with the disc jockey about to finish up his show. That morning his car had been stolen. Could I give him a ride to a friend’s apartment? He needed to pick up something. Sure, let’s go.

We got to the apartment complex. He jumped out of the car and was back in a flash. As we headed back into town, he pulled out a wad of cash from his pocket. “Nothing like a little payola to get you through some hard times,” he said. For some reason, I didn’t see that coming.

On the way back, the song, “Dazz,” by Atlanta's own Brick, came on the radio. “You know, we (his station) broke that record. Once we started playing it, we made it a hit.” His boast would have surprised many employees at Peaches who had watched “Dazz” sell in big numbers several weeks before my friend’s station added it to the playlist. Flush with payola, his confidence soared. He was a hit maker.

The City Breakin’ And Everybody Shakin’ … A lot of people in the business were under the impression, or let’s say the delusion, that they were responsible for records climbing the charts. Around the same time as the payola errand, there was a lunch with local Polygram promotion guys. They worked for Mercury and Polydor, where the hits had been few and far between the last few months. Then suddenly, fortune was smiling on our friends at Mercury. The label had two hit records from unexpected sources: The British band 10cc and soul singer William Bell. 10cc’s “The Things We Do for Love,” was a hit out of left field, peaking at number five in the U.S., while Bell’s “Tryin’ To Love Two” was an unexpected smash on the soul and pop charts. Both sold extremely well at Peaches Atlanta. The local Mercury guys were in the high life. At lunch they started talking with each other about how they had turned things around. Now they had hit records, bestselling songs they had guided up the charts! “Now, when I go to the radio stations, they have to give me respect,” said one. Another said, “Right, they know you’re walking in with hits.” Our lunch of salads and burgers was served with a heavy portion of locker room bravado.

By the time another year passed, a few hit records would not be enough for Polygram. All they wanted was everything. The Saturday Night Fever soundtrack, on RSO, was released in November ’77, just a month after the Bee Gees’ first new song from the album, “How Deep Is Your Love,” began its climb to the top of the Billboard Hot 100. The soundtrack featured two more new Bee Gees songs that would also hit number one, plus “You Should Be Dancing,” “Jive Talking,” their original version of “More Than A Woman,” as well as the version by Tavares. Then too was another Brothers Gibb composition, “If I Can’t Have You,” sung by Yvonne Elliman. Previously best known for her role as Mary Magdalene in Jesus Christ Superstar, Elliman was also heard on several albums with another RSO hit-maker, Eric Clapton.

The Saturday Night Fever soundtrack would stay atop the Billboard album chart for 28 straight weeks, eventually selling a total of 15 million copies. And if Polygram wasn’t busy enough with its RSO chart toppers, which included the soundtrack album to Grease, they were also the distributor for Casablanca Records, home of KISS, George Clinton’s Parliament-Funkadelic, and disco diva Donna Summer, the star of Thank God It’s Friday. Yes, the hits kept coming and Polygram was only too happy to remind its customers where the hits came from.

Early in the spring of ’78, Polygram hosted a gathering to promote the upcoming release of the Grease soundtrack. After “You’re the One That I Want” by John Travolta and Olivia Newton-John was played, the assembled retailers stood and cheered. They were so thankful for the miracles of RSO, turning out one big hit after another, creating box office magic with Sweathog Travolta, all the while turning Newton-John into a sex kitten. And there would be more hits by the Bee Gees, kid brother Andy Gibb, Donna Summer, and Eric Clapton extending deep into the next year. The people at Polygram presumed they were positioned to ask their customers for anything they wanted, even if it meant scamming history. In late May and early June of ’79, those Polygram people were working the phones.

Peaches Records and Tapes put out a trade report of its own, with hundreds of copies going to each of its two-dozen-plus stores so customers could read what records were climbing the charts at their local Peaches or a thousand miles a way.

So, there I was, early one morning in my office at Peaches Atlanta. The phone was ringing. It was one of my pals at Polygram, a merchandising guy, the low man on their totem pole. His superiors were sitting close by as he made with the opening pleasantries, and then with the demands. “We want your stores to report ‘Love You Inside Out’ by the Bee Gees number one when you talk to the trades this week — we need you to do this,” he said brusquely. The guy had a threat along with his request. If the Peaches stores in the Southeast, especially Atlanta, didn’t follow through with his “request,” then Polygram could pull all co-op advertising support that Peaches was due. Having just been named Regional Advertising Director, I saw he was hitting close to home. It was my job to procure advertising from the labels and distributors; going about my duties while lying, however, wasn’t the way we got the job done. The people at Polygram knew we played it straight. In fact, I mentioned that another of their releases, Donna Summer’s “Hot Stuff,” was our number one single again that week and we would report it as such. “Well, we want you to support all our artists, of course, but we really need your help on the Bee Gees’ single; if it makes number one on Billboard, it’ll tie the Beatles’ record,” my pal the shill replied, very frustrated for so early in the day. After a lot of back and forth and several long periods of silence, I told the guy we didn’t play games when reporting sales and that we hoped the distributor didn’t pull the co-op advertising we had rightfully earned. He grumbled, hung up and then went on to complete his round of friendly calls.

So strange. That week, I had talked to other Polygram offices in my region, covering seven big markets. Only in Atlanta were we getting this pressure.

An hour later, we put in a call to our headquarters in LA about the attempted strong-arm on behalf of the Bee Gees. The founder and president of Peaches Records and Tapes, Tom Heiman, was fond of his employees and grew irritated whenever the record companies sought to pressure them. Heiman may have called Polygram’s chieftains or maybe he didn’t, but as the day moved along, we heard no more about a loss of advertising dollars. By the next week, conversations with the Atlanta Polygram representatives took place as if there had been no conflict. Besides, RSO and Polygram had apparently been successful enough with the nationwide bullying to get the Bee Gees their dubious number one.

When it was announced the Bee Gees had tied the Beatles’ records for most consecutive number one U.S. singles, people inside the business could only shake their heads. “Love You Inside Out” was hardly a number one single; in fact, at Peaches Atlanta, it stiffed. The idea of reporting it as the top seller that week wasn’t only dishonest but laughable. Even though John Lennon once said the Bee Gees “do a damn good job,” there was still resentment about their encroachment. Many in the Beatles’ faithful regarded the Bee Gees as a band who once did a “damn good job,” but now recorded silly dance music for the singles bar scene, where middle-aged guys in leisure suits chant over and over, “Ah ha, ha, ha, stayin’ alive…” These were not the Bee Gees of the late 60s and early 70s. When judging the Bee Gees’ consecutive half-dozen number ones with those of the Beatles, comparisons were painful. From late ’64 through late ’65, The Beatles topped the U.S. charts six straight times with “I Feel Fine,” “Eight Days A Week,” “Ticket to Ride,” “Help,” “Yesterday” and “We Can Work It Out.” Those singles had the ring of authenticity – and greatness – about them, each with solid flip sides, such as “She’s a Woman,” “I Don’t Want to Spoil the Party” and “Day Tripper.” There’s little wonder why coercion was needed to get the Bee Gees a share of that record.

Not all of the Polygram Atlanta office employees called us with offers we couldn’t refuse. There were some very good people in their sales and promotional departments who understood the value in working together, not against each other. This was 1979, a prosperous time for the record business, but a former Polygram employee remembers how miserable those days could be. He and his coworkers thought it was crazy their labels were fighting over the sales reports. Under the same roof, it was the Bee Gees versus Donna Summer, the Village People versus Eric Clapton, etc. There was plenty for everyone, but some wanted more and the ends justified the means. One employee called it “a very threatening time with our company.”

Instant Karma’s Gonna Get You… Eventually the American public gets it. By early ’79, the disco plague was easing, but it wasn’t finished. Certainly not in Miami, Florida, roughly 20 miles south of Hollywood, where the National Association of Record Merchandisers convention would take place in March. South Florida was still a disco haven. And to top it off, the Bee Gees would perform live at the NARM convention. Happiness, naturally enough, abounded for many of the conventioneers. They would get to see the act responsible for making their cash registers ring the last three or four years. On the morning after, to hear them talk about it in the hotel cafe, the Bee Gees could do no wrong. “Oh, they’re something else,” said one old merchant, thankful for the productive work of Mr. and Mrs. Gibb in the late ’40s. But elsewhere a Bee Gees backlash was brewing. Some radio stations were featuring “Bee Gees Free Weekends.” What took them so long?

It would be ten more years after the “Love You Inside Out” scam before the Bee Gees scored another top ten single in the U.S., but the Brothers Gibb, especially Barry, hung in there. There was Barry Gibb on a Barbra Streisand hit. Then it was Barry with Dionne Warwick. That was followed by Barry with Kenny Rogers and Dolly Parton. The airwaves were filled with Barry Gibb productions. It was music for people who really didn’t like music as they headed to the malls. Maybe someone seeking relief could turn the dial and find an oldies station playing “Lonely Days,” a Bee Gees song that John Lennon would say was “damn good.”

No idea about music production and composition. Bee Gees six top hits have no comparison and none artists can emulate their style. Only Yesterday have the same music quality as How deep is your love but not in interpretation. Music is music, no words... The Beatles had the same reception you are saying about the Bee Gees and many jokes aired about dumb songs as Yellow Submarine, Obladi oblada, She loves you... Yeah, yeah, yeah.... The composition, music treatment, harmony and orchestration from SNF and Spirits have no comparison in music history. And then... The most successful album from Streisand, one of the best albums of all time. The greatest hit for Warwick in her life, the most successful country song in history Islands in the Stream...all that being banned from USA radio stations. What are you talking about? You win again could be the greatest n1 top in USA too, they over sell George Michael's Faith in Germany and UK... All about quality of music because they don't dance... Staying alive is the most important song in dance music and dance needs music! It's talks about life and survability. The Beatles were a good band, more important in social media than in music influence. Lonely days is a good song but the Bee Gees have, literally, 100 better songs.

None of this takes away from the Bee Gees’ great talent, versatility, hard work and accomplishments. As a kid in the 70’s, I was drawn to the Bee Gees’ music because it was good and I liked it. From there, I explored their earlier work and loved them even more. To say, that I was manipulated is utterly false and insulting. Their success was not the result solely of record company interference. The Bee Gees were determined, ambitious, and hard-working musicians, beginning in the 1950’s as young boys. They continued to consistently create wonderful music until Maurice’s passing in 2003. To dismiss their almost 50 year career, is indeed, mean-spirited and hateful.

Also, you fail to mention the hate and record burning campaign instigated by that racist radio personality in Chicago. And the subsequent deliberate deprivation of airtime by US radio stations. Meanwhile, in Europe and in other parts of the world, their music was played and received very positively.

To me, and millions of others, no one will ever outshine the BeeGees. (Plus they were/ are kind and decent human beings).