Peter Buck heard things differently. His musical preferences were not those expected of a suburban Atlanta teenager. Among his favorite bands were Iggy and the Stooges, Crazy Horse, and the Velvet Underground.

In a conversation with rock journalist Anthony DeCurtis, Buck recalled marching to his own drummer, “Living in Roswell, Georgia, in 1971, everyone liked the Allman Brothers. I can’t tell you why; that’s all there was to it. It was a law.”

1971 was the year of The Allman Brothers Band at Fillmore East, a classic that set the standard for live albums in all genres of popular music. The album made a powerful impact, causing millions to take notice of the group working out of Macon. The Allman Brothers Band was considered the best rock group in America, maybe the world, but to rock fans in Peter Buck’s neck of the woods, they were the pride of Georgia.

When he spoke with DeCurtis in September ’94, Buck’s band, R.E.M., was at the top, like the Allman Brothers Band two decades earlier. R.E.M.’s ninth album, Monster, had just been released, debuting at number one on the Billboard charts and receiving four and a half stars in the Rolling Stone review by Robert Palmer. As with the Allman Brothers Band, R.E.M. had long received positive reception from the critics. In 1987, the cover of Rolling Stone declared R.E.M. “America’s Best Rock & Roll Band.” And yes they, too, were the pride of Georgia.

The period of popular and critical success achieved by the Allman Brothers Band was not as sustained as what R.E.M. achieved. R.E.M. stayed busy from 1981 through 2011, recording fifteen studio albums, one EP, and two live albums.* They compiled a brilliant body of work. R.E.M. was also free of the tragedy and heavy drama associated with the Allman Brothers Band. But those hard knocks, brought on internally or by fate, added to the the Allman Brothers Band’s legacy, and for a time, generated even more loyalty from rock fans, especially in the South. In his reminiscing about the early ’70’s, Peter Buck touched on something intangible, but that something was real.

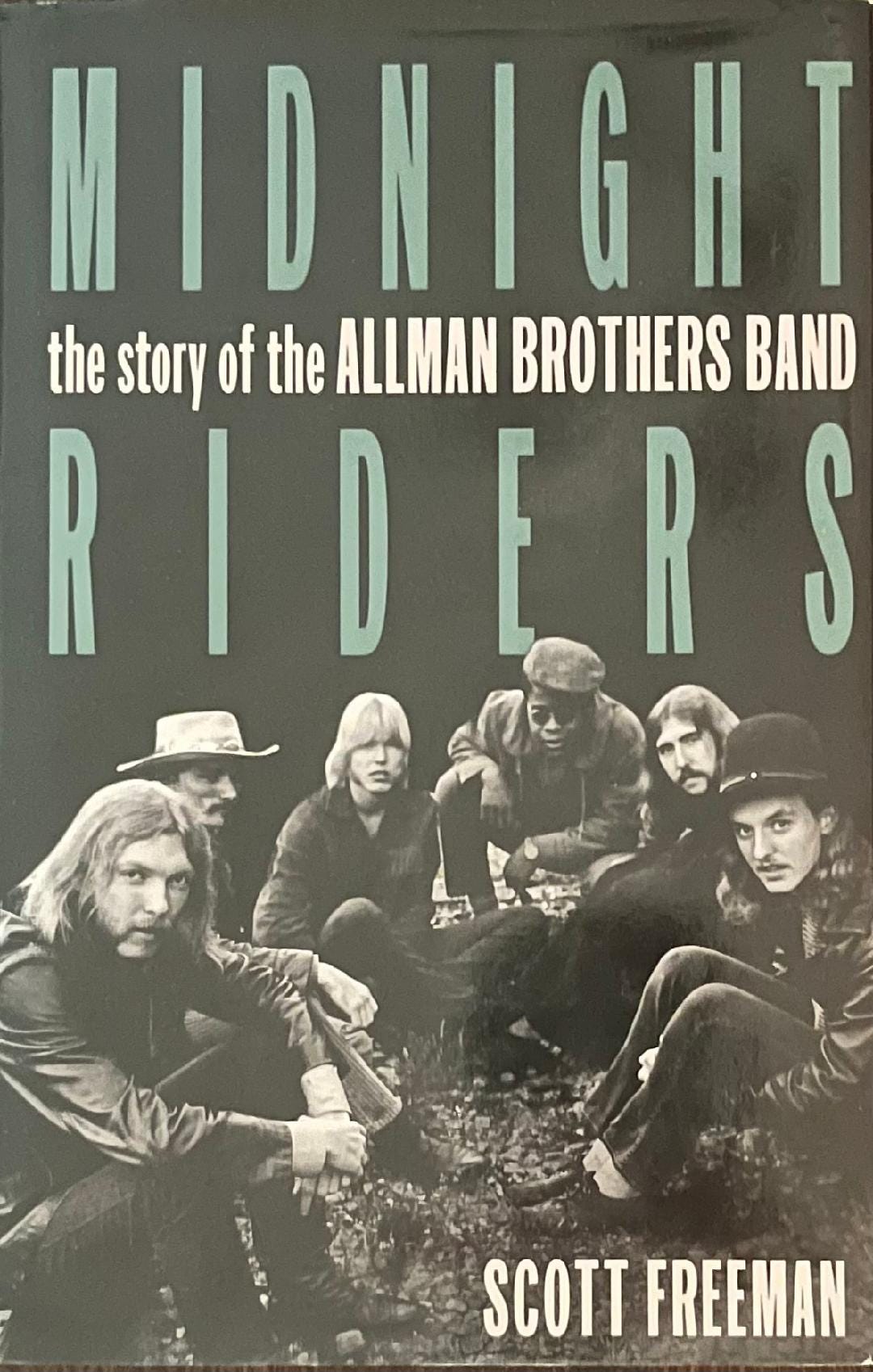

Followers of the Allman Brothers Band went beyond enthusiasm. They weren’t just admiring fans. They felt strong allegiance to the band. Scott Freeman, author of Midnight Riders, the Story of the Allman Brothers Band, remembers the devotion, and the historical aspects, declaring, “The Allman Brothers Band was the first rock band to emerge from the South in the post-Civil Rights era, reflecting a new South. They had guys of color in the band, which couldn’t have happened even five years before ABB formed. What the Grateful Dead was to San Francisco, the Allman Brothers Band was to the South. They gave young Southerners reasons to be proud of their heritage. The Allman Brothers Band represented something bigger. To be cool and hip in the South at that time, you were into the Allman Brothers Band.”

The support of the band became even more fervent after the tragic loss of Duane Allman. Fans deeply believed the Allman Brothers Band would carry on. But a band doesn’t replace a Duane Allman. He and fellow lead guitarist Dickey Betts created stunning and exuberant music. Perhaps another guitarist could join Betts, replicate some of Allman’s guitar licks and it would all sound great. That, however would not be enough. There was the vision Duane Allman shared with his bandmates that made their music soar. Duane’s spirit had long pushed the band, just as his playing did. The surviving members would glean from what they had shared and chart a new course. The old sounds would blend with new sounds. Inspiration would guide the Allman Brothers Band and their road would go on forever after all.

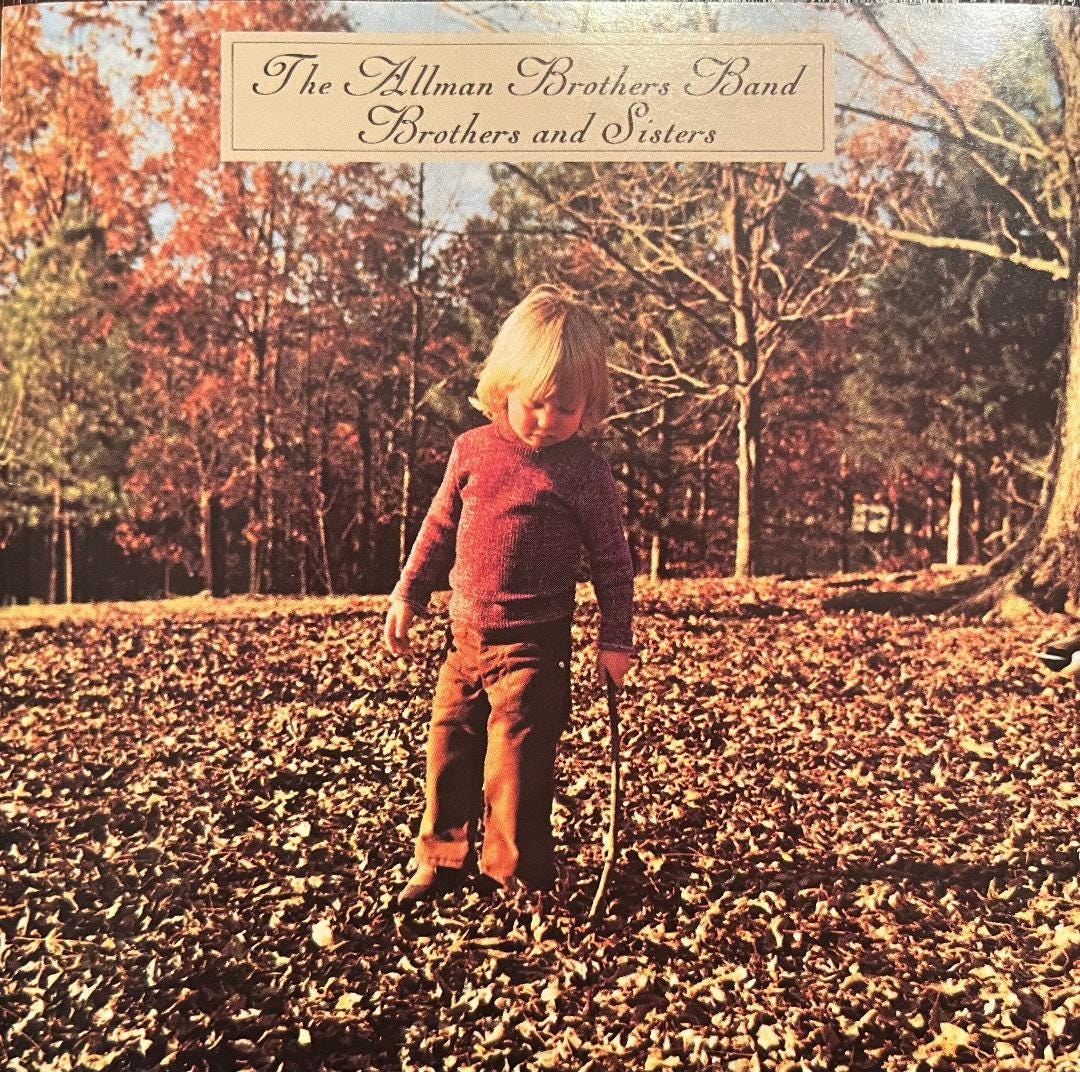

Johnny Sandlin, the Allman Brothers Band’s producer, had his own inspiration. He was convinced the band could expand its sound and renew its spark not by adding another guitarist, but a pianist. Dickey Betts would handle the majority of the guitar work, and he would add more of a country inflection to a few of the band’s new songs. On Sandlin’s urging, Chuck Leavell was selected to play piano on the band’s album, Brothers and Sisters, taking shape in the fall of ’72, just a year after Duane Allman’s death.

With Leavell on board, the band quickly recorded “Wasted Words” and “Ramblin’ Man,” two great songs revealing a determined band in an expansive mode. The guys were feeling relaxed and optimistic but tragedy lurked. On November 11, the band’s bass player, Berry Oakley, just like Duane, was killed in a motorcycle accident, colliding with a bus, eerily enough, within 1000 yards of where Duane’s Harley collided with a truck.

The mood changed quickly. Was the band cursed? The guys could not be blamed for thinking so. In the process of recording their first complete album without Duane Allman, they lose their brilliant bassist with the uniquely melodic touch. But throw in the towel? No way. There was an album to finish. In Lamar Williams, they found a bass player with a different, funkier style, but one who blended in seamlessly as the band returned to its mission. In the next year on the first day of August, Brothers and Sisters was released. Mission accomplished. Redemption was heard from turntables and tape decks throughout the western world but particularly in the American South. The sounds of Brothers and Sisters were those of victory and the sounds of major challenges met. It’s unlikely any music in the South was ever as celebrated and taken to heart so quickly as that long-awaited album by the Allman Brothers Band.

Brothers and Sisters spent five weeks at the top of the U.S. album charts. Its first single, “Ramblin’ Man,” peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100. The Allman Brothers Band not only delivered their best studio album in a trying and tragic period, they created a rock and roll classic. To this day, the album sounds as fresh and exciting as it did 51 summers ago.

In Midnight Riders, the Story of the Allman Brothers Band, Scott Freeman expressed great enthusiasm for each of the songs on Brothers and Sisters. Especially captivating to Freeman was “Southbound,” the track that kicked off the album’s second side:

“Southbound,” written by Dickey and sung by Gregg, begins on a fevered pitch and never lets up. It is a song of swaggering lust, about a man headed home after a road trip and anticipating a heated reunion with his woman. The song has a furious and inventive buildup underneath the chorus and Chuck’s rhythm parts are full of wonderful surprises. The solos on “Southbound” are two sides of passion: Chuck’s piano is melodic and gentle, as it shifts between styles with graceful flair; Dickey takes no fewer than three guitar breaks, each bristling with a hot-blooded erotic undertone.

Scott Freeman is correct. “Southbound” never lets up. It’s a pulsating song of the road, alive with the promise of a most desired destination. As Gregg Allman sings “I’m coming home to you,” one visualizes how he’d count the miles, heading south on I-75. Detroit. Toledo. Cincinnati. Lexington. Chattanooga. Atlanta. Finally the happy homecoming in Macon.

“Southbound” confirms Johnny Sandlin’s idea about expanding the band’s sound with a pianist, especially a pianist like Chuck Leavell, as one of sheer genius. When contacted, Leavell remembered the song being as much of a revelation to play as it’s been for the millions who have heard it. He recalls the time in the studio as if it was yesterday.

“Recording “Southbound” was a real joy for me, “Leavell says. “A great uptempo blues number that Dickey Betts wrote. I was glad that he wanted Gregg to sing it, as it fits his voice so well. We all loved the riff that leads up to the solos and that ends the song….a really cool ascending pattern that swings as it rises. The breaks on the intro were also very cool…typical blues breaks, but fun and exciting. As we played the song live, we expanded those breaks which made it even more exciting on stage. As for my own solo, I tried to jazz it up a bit…using a “9” chord on my left hand with the 3rd on the bottom and the 9 on top. My right hand started out with octaves and then progressed to single note riffs. It was huge fun to play!”

The songs of the Allman Brothers Band, “Southbound” and many others, signaled fun and adventure down the road. But not all the times ahead, even those less than a year away, would be so rewarding. However, the Allman Brothers Band had already achieved greatness long before their first break-up in 1976. Spirited renewals would guide the band on a pair of comebacks, the final one commencing in 1989 and lasting 25 years.

On October 28, 2014 the Allman Brothers Band went out in a blaze of glory at New York’s Beacon Theatre, a place that felt like home. Over the years, they hit the Beacon’s stage for 238 consecutive sell-out performances. On that final night, they left the audience believing the road really could go on forever.

*R.E.M. has released three additional live albums since their breakup in 2011.

Both Lynrd Skynrd and the Allman Bros had roots in Jacksonville, Florida. I think you got the Allman Bros exactly right: they represented the “New” South. Lynrd Skynrd on the other hand seemed to celebrate a different persona.