“Mister Moonlight” is often called The Beatles’ worst recording. It doesn’t show up on any lists of fan favorites. Most critics don’t like it either.

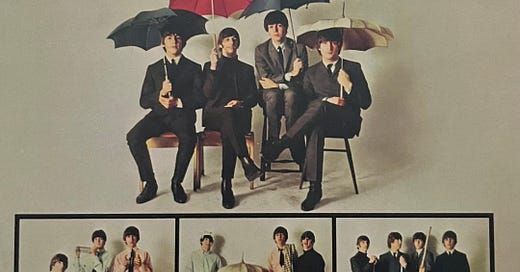

In less than two and a half years, beginning in June 1962, The Beatles had their most prolific period in the studio. At least 70 songs were recorded during that time. The vast majority of the songs were received enthusiastically, but not “Mister Moonlight.” It was included on the albums, Beatles For Sale (UK) and Beatles ’65 (US), both released in December ’64. Few recordings by major acts have been so roundly dismissed. In books on The Beatles, “Mr. Moonlight” has been singled out as an odd choice for the respective albums as well as proof the band was not immune to lapses in taste.

Ian McDonald in Revolution In The Head, refers to it as a “gross quasi-calypso” and he cites John Lennon’s “berserk delivery.” and Paul McCartney’s “ghastliness” on the Hammond Organ.

Mark Hertsgaard in A Day In The Life, The Music and Artistry of The Beatles wonders why the song made the cut at all when their “vastly superior” cover of Willie John’s “Leave My Kitten Alone” could have been included.

Mark Lewisohn, in The Beatles Recording Sessions, indicated The Beatles were not sure what exactly to do with “Mr. Moonlight.”

Jonathan Gould in Can’t Buy Me Love called the song “ill-fated” and Lennon’s vocals “over the top.”

In Tell Me Why, a commentary on The Beatles’ recordings, author Tim Riley is not as harsh as McDonald or Gould, acknowledging “Mister Moonlight” as “one of their most peculiarly engaging covers.” But then Riley calls it a “musical guffaw.”

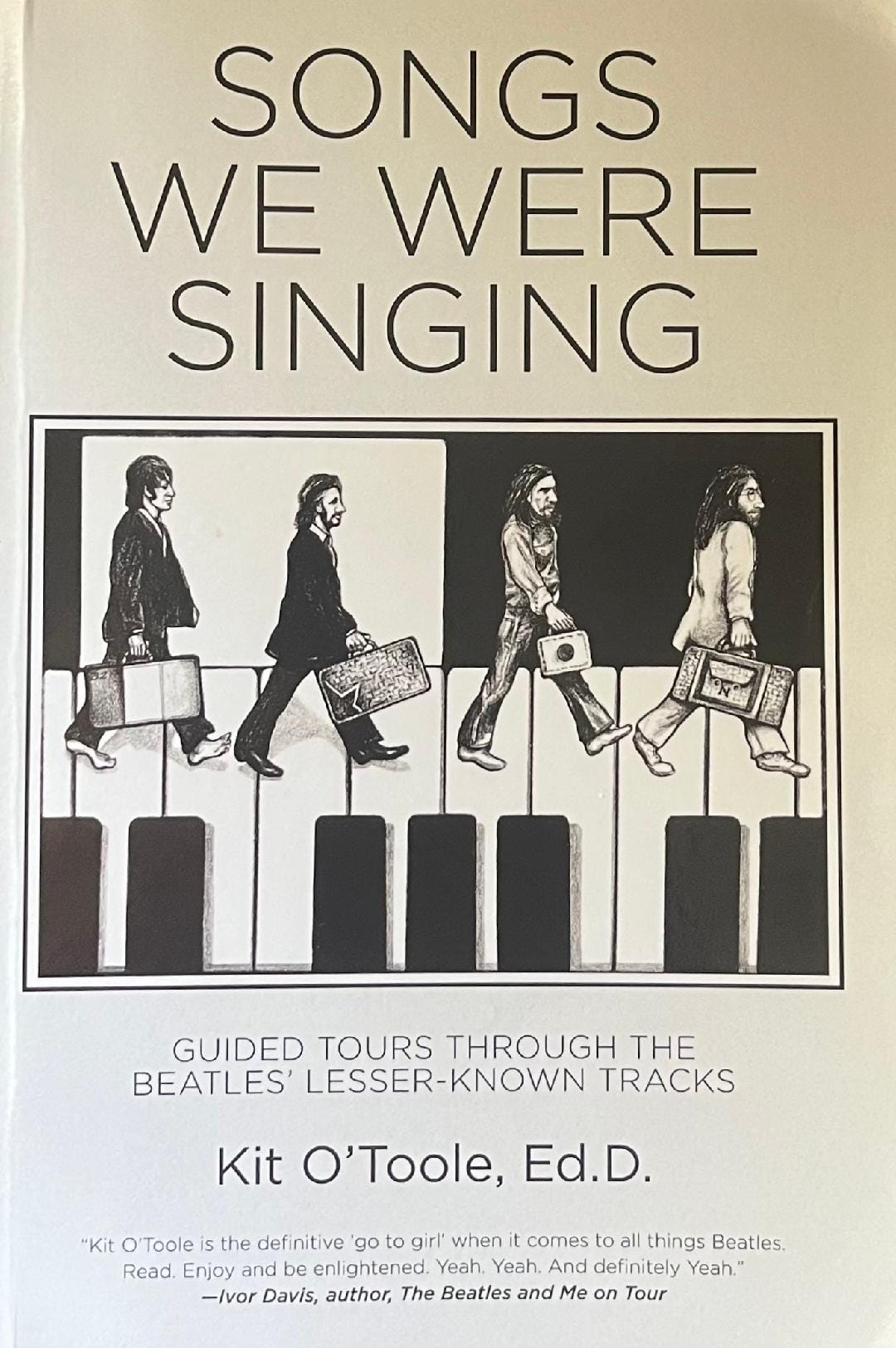

Yet Beatlefan Associate Editor Kit O 'Toole isn't guffawing over "Mr. Moonlight." She takes the song quite seriously. In her book, Songs We Were Singing, O'Toole offers a spirited defense of "Mr. Moonlight." O'Toole has high praise for Lennon's vocal performance, writing that when he shouts "Mister Moonlight" at the song's beginning, “one can hear his cords shredding a la ‘Twist and Shout.'"

O'Toole advises listeners to focus on Lennon's "shiver-inducing vocals, the patented Beatles harmonies and Harrison's and Starr's gentle percussion." She does concede the recording would have sounded better if Harrison's guitar solo, as featured in their live performances of the song, had been included as opposed to McCartney's Hammond organ solo, which O'Toole calls "straight-out-of-a- roller rink." In closing, she finds "Mr. Moonlight" not guilty of being one of The Beatles' worst songs.

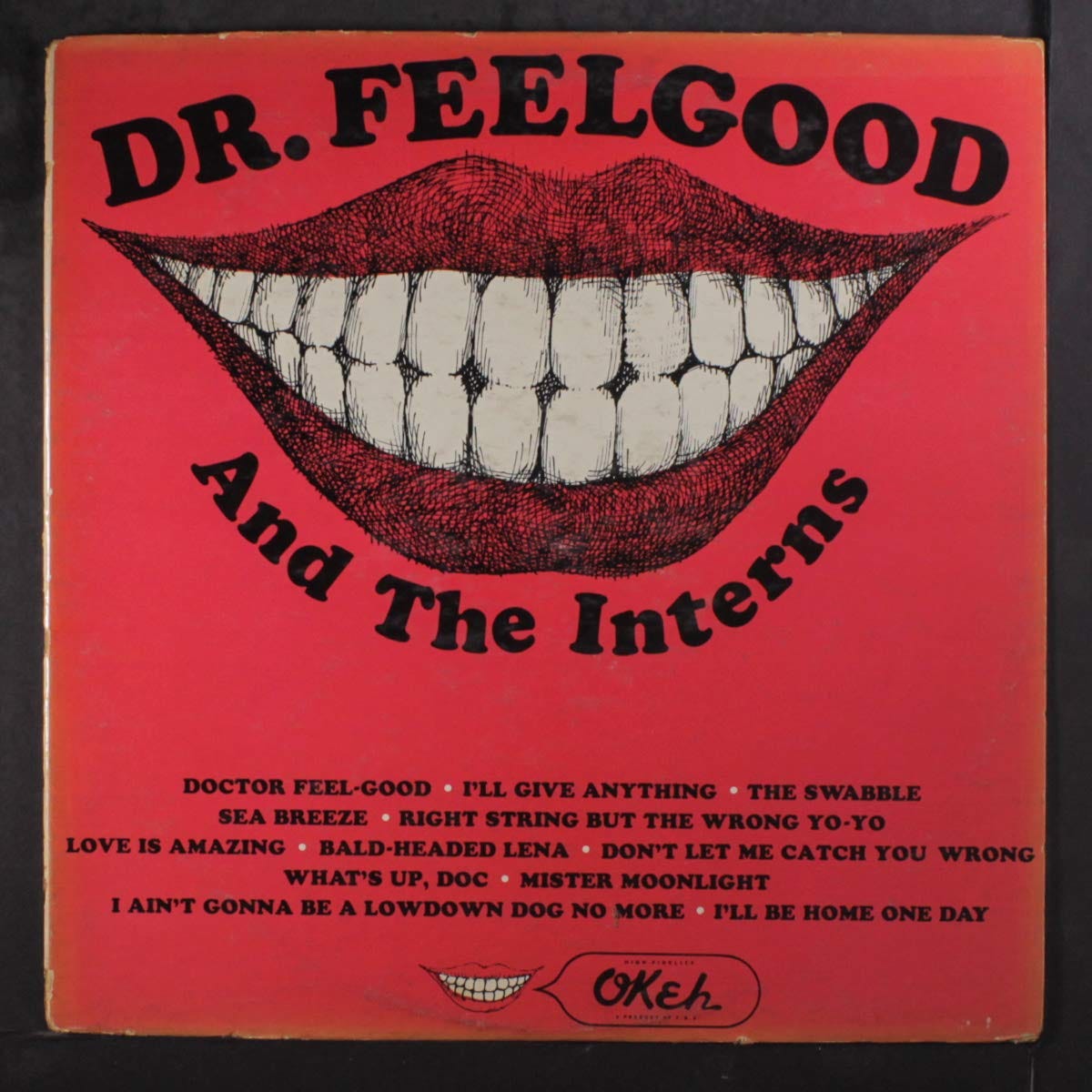

”Mr. Moonlight,” was favored by many British bands in the early ’60s. The Hollies also recorded it for their debut U.K. album, Stay With The Hollies, as Graham Nash hit the high notes with blazing speed. What was to explain the popularity of this previously obscure song? It was only the flip side of a single, “Dr. Feelgood,” by the rhythm and blues band, Dr. Feelgood and The Interns. Dr. Feelgood? Who was that? What did he do?

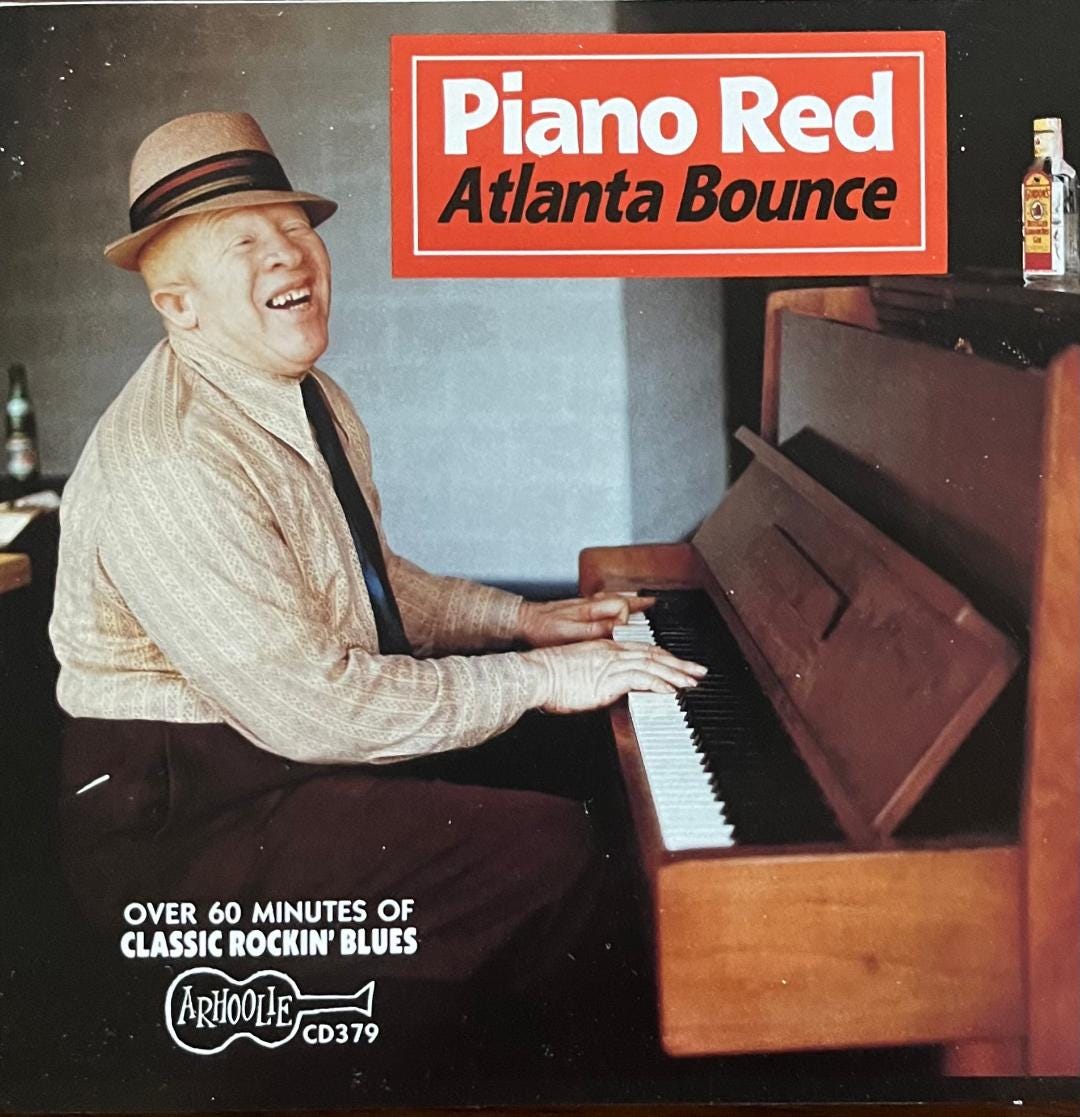

Dr. Feelgood practiced music, doing some of his best work on the 88s in the window of Muhlenbrink’s, an old Underground Atlanta nightclub. Over a ten year period, beginning in 1969, the Doctor was In — most every night, most every week. During that time, he was known again as Piano Red, as he had been for most of a career that dated back to the ’30s. Perched on his stool atop a three-foot riser in the Muhlenbrink’s window, Red played barrelhouse blues piano for more than a million people during those ten years at the club. Even as attendance at the original Underground Atlanta declined in the late ’70s, Piano Red kept drawing the people to Muhlenbrink’s. “Red was special,” the late Jack Tarver, Jr., co-owner of Muhlenbrink’s, would often say.

Red’s special life began as William Lee Perryman on October 19, 1911 on a farm near Hampton, Georgia, where his parents worked as sharecroppers. In an interview he gave to Atlanta author Murray Silver, Perryman talked about his early life. When he was six, his parents decided to give up farming and move to Atlanta. Perryman said, “I had a brother named Rufus who was old enough to work. Him and Daddy found a job at a place called the Miracle Machine Shop. Rufus was an albino like myself, and couldn’t do nothin’ but certain types of work because he was nearsighted like me, but they had some work for him.”

Perryman’s mother, Ada, had high hopes for her children. When the Perrymans had been in Atlanta for about a year, she said, “I wish I could get a piano for all you kids. Some of y’all might learn to play like your brother Rufus.”

Rufus Perryman, also known as Speckled Red, learned to play on a church pump pedal organ. Eventually he quit his day job and began playing at house parties and fish fries. Decades later, Red said he was not sure if “they was payin’ him or not. He had a place to stay and that’s all that mattered to him. He’d be gone two, three days. Sometimes we didn’t see him for a week.”

Mrs. Perryman did not give up on hopes of getting her kids a piano. Red remembered that it cost her a dollar down and a dollar a week. He spoke of his mother’s determination, “Mama cooked and washed and ironed for people and she got that piano.” He would always remember his mother’s great gift. “It was a Gainesborough upright, probably not a new one, but it was a good ‘un. That was the greatest thing that ever happened. We had a piano in the house.”

By the time he was 12, Red was pounding the keys like a pro. Influenced first by Rufus and later by the recordings of the legendary Fats Waller, he made a name for himself, eventually working with the great blues artists Barbecue Bob, Curley Weaver and Blind Willie McTell. From the early ’30s into the early ’60s, he worked his way through the segregated South, playing in Black clubs as well as the white establishments. He also played at college parties. Red’s exuberant and raspy voice was the perfect match for what he called his “ping-ponging and banging” on the piano. Wherever he played, he made the blues a cheerful endeavor.

But delighting the crowds wasn’t enough to pay the bills. Red also worked as an upholsterer and most notably as a disc jockey on Atlanta radio stations WGST and WAOK throughout the ’50s and ’60s. In the early ’60s Red assumed the name “Dr. Feelgood” on the radio and in live appearances. In performances, his band, The Interns, would be dressed as doctors and nurses.

It was in 1962 that Dr. Feelgood and The Interns scored a minor hit single with the song, “Dr. Feelgood.” The flip side was “Mr. Moonlight,” written and sung by Intern Roy Lee Johnson. A native of Heard County, Georgia, Johnson went on to great acclaim as a blues singer and guitarist, but the peak moment of his career might have been a couple of weeks after Perryman fired him, apparently in the mid '60s, when he got a phone call about a big royalty check. In a 2014 edition of Living Blues magazine, Johnson told Gene Tomko of the riches that came his way after The Beatles recorded his song:

“I couldn’t believe it , man. I thought someone was trying to trick me. Fifty thousand dollars! I didn’t even know what fifty thousand dollars looked like! I went out there. I was scared to really take it! I didn’t know it could be so good. What makes it so bad about it, it kept on coming. It scared me almost crazy. That was a lot of money back then.

“I actually cried when I got that money because it sure came at a needed time. My wife was pregnant and we were living in one room and another guy was staying in another room with his wife. Something had to be done.

“A lot of people may dislike me for it but I’m glad they cut my song, man. I’m really proud of it. Sometimes I have to scratch my own self to see if I’m alive, you know? That doesn’t happen to everybody every day.”

Johnson could look back to his teen years when he’d sing “Mr. Moonlight” and his classmates would tell him, “Your little old song ain’t nothing. Nobody wants to hear that!” As it turned out, because of The Beatles, millions heard Johnson’s “little old song.” Not all that surprisingly, many people preferred the version he recorded in1962.

With Johnson’s fine vocal leading the way, “Mr. Moonlight” by Dr. Feelgood and The Interns is easily the superior rendition. Their recording offers a subtlety missing from The Beatles’ version. Listening to the original and knowing John Lennon’s love for American rhythm and blues, it’s understandable that he and the other Beatles were eager to record the song. However, Lennon’s extreme vocal treatment struck many as curious. Did he camp it up or was he in such awe of Johnson’s command of the song that in order to deliver a worthy rendition he simply overreached?

That brings us back to Kit O’Toole’s take of The Beatles’ “Mister Moonlight.” The opening of the song in which Lennon appeared to nearly rip his vocal cords by shouting/singing the two words “Mister Moonlight” can be unnerving. Perhaps Lennon’s approach is, as she noted, reminiscent of his joyful charge through “Twist and Shout,” but his demonstrative calling out to the song’s subject in the opening five seconds is fearsome. Such awe conveyed with those four syllables! That’s how Lennon came across when I first heard the song in December '64 and sixty years later the effect is still the same. All in all, O’Toole nails it when she calls Lennon’s performance throughout the song “shiver-inducing.” Lennon all at once sounds frightened, enthusiastic, and serene.

In the nearly two decades after The Beatles recorded “Mr. Moonlight,” William Lee Perryman, known again as Piano Red, continued to play in Atlanta and elsewhere, including The Montreux Jazz Festival. One Atlanta gig was a surprise, perhaps even to Red. On May 10, 1979, The New Barbarians, a band including Keith Richards and Ron Wood of The Rolling Stones, were scheduled to play The Omni. For one reason or another, the band was late, quite late, in getting there. So in the meantime, Piano Red, announced as a longtime friend of the Rolling Stones, took the stage and played to the delight of thousands. Even in a setting void of the usual intimacy, Piano Red worked his magic. He played the favorites, including “Red’s Boogie,” and “Right String But The Wrong Yo-Yo.” It was a great moment, unexpected as it was, in Atlanta’s musical history.

There were thousands at The Omni that night who saw what they had been missing all those years at Muhlenbrink’s. But opportunities to see Piano Red perform remained. For a time in the early ’80s, he appeared at the old Excelsior Mill on North Avenue, not far from Georgia Tech. He appeared on Channel 17’s Tush. William Lee Perryman kept spreading his joyful variation of the blues for as long as he could. Sadly, he was diagnosed with cancer in 1984 and passed away on July 25, 1985.

Among those attending Piano Red’s funeral were Georgia Governor Joe Frank Harris and Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young. Surely there were great stories told about Red that day. His old boss and friend, Jack Tarver, Jr., had a lot of stories about Red and he treasured them. Tarver remembered Red as “being happy to be able to make a living doing what he loved.” He mentioned the live album Red recorded at Muhlenbrink’s. Upon taking the tapes to the studio, an engineer assembling the recordings for release asked about the bass he heard on the songs. “That wasn’t a bass, it was Red’s foot stomping along as he played,” Tarver recalled.

Tarver said they pressed 1000 copies of the album for sale. There were 25 copies per box. Tarver would give Red a box to sell, agreeing they would split the proceeds. Soon Red came back asking for another box. Tarver asked about the earnings from the first box and Red said something about his sister needing the money. Tarver went ahead and gave Red the next box. Why not? It was small compensation for the joy that Red brought to Tarver and a million others who saw him those 10 years in Muhlenbrink’s window.

What a great story, Jeff! Thoroughly enjoyed it. Red got over to UGA frequently and always delighted the crowd.

Great story. Thanks for telling it.