The South and A Large Time for Music

Full Disclosure: Bill King and I have been friends for nearly 50 years. The first time we met was when he came by the Peaches Records and Tapes in Atlanta to interview company founder and president Tom Heiman. I handled the store’s advertising and promotions at the time and was told in no uncertain terms to get Tom interviews with Atlanta media. An accommodating soul, Bill appeared at the store shortly after Tom arrived from L.A. The interview moved along nicely and Bill put together a good story for The Atlanta Constitution, where he worked the entertainment beat, with a special emphasis on the growing southern music scene.

A few years later I began working in advertising sales at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution and for most of the days over the next 27 years, I would see Bill and we’d talk shop, with each discussion leading to a favorite subject, The Beatles. Bill discovered a way to share his knowledge of The Beatles in 1978, when he and his wife, Leslie, founded Beatlefan magazine, still in print and thoroughly covering a band that broke up 54 years ago and continues to be more vital than any band since. Over the last ten years, I have served as a contributing editor at Beatlefan, writing book reviews and the occasional feature.

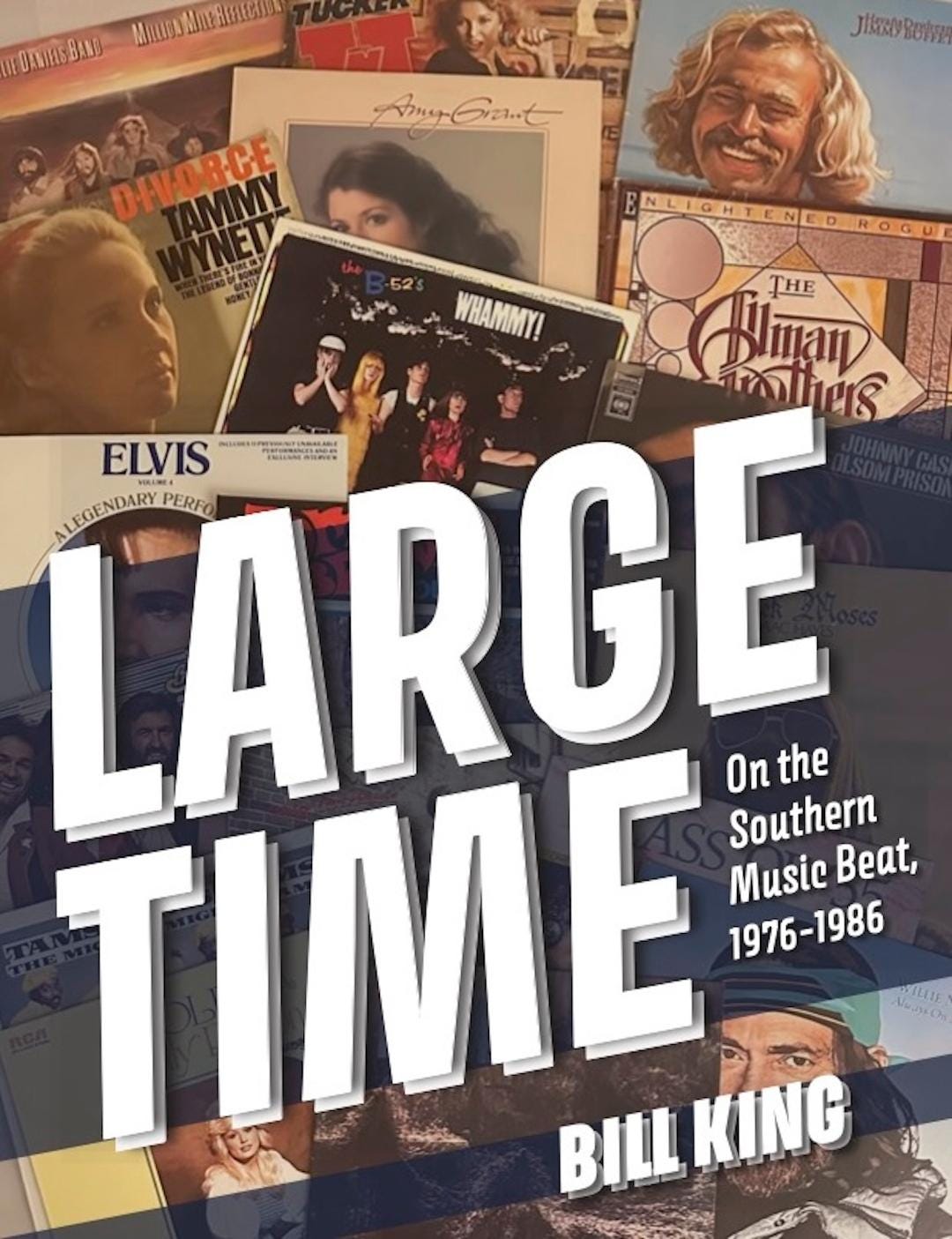

Bill King has contributed to Bruce Spizer’s excellent books on The Beatles’ albums, and it’s long been hoped he would produce a book of his own. Now we have it, Large Time, subtitled On the Southern Music Beat, 1976- 1986. A native Georgian, King began his 10-year stint as the Constitution’s first full-time entertainment reporter in ‘76 when an editor decided Atlanta actually had a popular music beat worthy of regular coverage. Those of us in the business could have told them that several years earlier. In one of the city’s alternative papers, Atlanta rock impresario Alex Cooley said in an interview that The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution had stunted the local music scene’s growth with its indifference. Both papers (owned by Cox) took pride in covering the region, and particularly all corners in Georgia, but as the ‘60s turned into the ‘70s, their readers had very little chance of reading anything substantial about Joe South (from Atlanta), The Allman Brothers Band (from Macon) or even James Brown (from Augusta, but born in Barnwell, South Carolina).

Brown had been recording hit singles since the mid ’50s, and in ’63 scored big-time with his Live at the Apollo album, which spent 66 weeks on the Billboard Top Pop Albums Chart, peaking at number two. He was among the nation’s top R&B artists into the mid ’70s, but then launched a comeback in 1980 with his appearance in the film, The Blues Brothers. It was in ’80 that King journeyed to Augusta to interview Brown for an article in the Constitution. King’s chapter on the Brown interview is one that demonstrates his skill in getting subjects to talk and getting the more loquacious subjects to talk a lot, as with James Brown. There have been very few artists whose rambling discourses can be considered performances but Brown had it working.

King puts us in a Mercedes 450 SE with Brown behind the wheel, talking about James Brown. The driver as great storyteller expounds on philosophies of life, his four years in reform school (Brown called it “prison”) for stealing hubcaps, his entry into the entertainment business and how he helped those who helped him, like his mother, and Little Richard’s manager, Charles Brantley, who convinced King Records owner Syd Nathan to release Brown’s first single, “Please, Please, Please” in 1956:

“He was the man who saved me, and I have him now in a rent home. Everybody went off and left him. Nobody got room for older people, and that’s wrong. My mother and my father parted when I was 4 years old. You know where she’s at now? In my house.”

Or he’d stew over those who didn’t appreciate him:

“It’s the white people who brought me back. Ain’t nobody done more for Blacks than me, but it wasn’t the Blacks who done it. I went to Richard Nixon to ask for a Martin Luther King holiday and the Black people called me the worst n——- ever.”

“I was like a gold mine sittin’ there. And unfortunately, the educated Blacks — we call ‘em Negroes — they were in a position to do it, but they had a lot of jealousy and they wouldn’t. Poor Blacks didn’t know anything about it. They thought I just wasn’t cuttin’ good material. They didn’t know I wasn’t cuttin’ records every four or five months and the record company was tryin’ to hide ‘em, ‘cause they were trying to sell other people.

But the Godfather of Soul wasn’t shy about selling himself:

“I know I’m a model man,” he said with such sincerity that it didn’t come across sounding conceited. “I know I can do a million things right and ain’t nobody gonna say anything about it, but I do one thing wrong and it’ll be in all the publications in the world.”

Brown went on to tell King that “Every minute of the day I’m doin’ something for humanity.” Maybe so. Brown certainly gave King enough material to truly entertain his readers.

There are over four dozen recording artists profiled by King in Large Time. For the most part, the best profiles are on recording artists who experienced success during King’s ten years on the Southern music beat. Among them are Dolly Parton, the Allman Brothers Band, Jimmy Buffett, B. B. King, Willie Nelson, Lynyrd Skynyrd, the Atlanta Rhythm Section, Lionel Richie, and perhaps the most innovative and wide-ranging rock band to emerge from any region in any country in the last quarter of the 20th century, R.E.M..

King’s chapter on R.E.M. reveals the band’s approach to creating their first E.P. and their first two albums that followed. R.E.M. had first generated attention in Athens, playing at University of Georgia student parties and local clubs. The UGA kids liked them. Always willing to provide insight into their music, members of R.E.M. easily opened up to King, particularly upon the release of the their debut album, Murmur.

Lead guitarist Peter Buck acknowledged Murmur’s sound was more commercial than that of their EP, Chronic Town, “but we didn’t plan it that way. I think it was that we were a little bit more knowledgeable about going into the studio and putting the sounds down.” He also noted while they were recording Chronic Town, an exceptional 5-song collection, that “we didn’t know what we were doing …. and we used anything that came into our heads.”

Historically, R.E.M. didn’t wait for musical notions to pop into their heads; they worked hard, expanding on the music they learned growing up, developing ideas from a wide range of influences, not just from the rock idiom, but also from other genres. As their body of work grew, it was as if R.E.M. embodied the spirit of The Beatles’ “White Album.”* Just think on how The Beatles closed the first side of that two-disc set with the dark and pulsating “Happiness Is A Warm Gun” and then opened the next side with the sprightly “Martha My Dear.” Then more than two decades later, on their ‘91 album, Out of Time, R.E.M. opens side two with the very pop-oriented, bubble gum-flavored “Shiny Happy People,” which sounds as if it were written for the Sesame Street audience. And in fact, they would perform the song on Sesame Street several years later. It’s a delightful work in spite of itself. Closing side two is “Me in Honey,” a brooding but dance-worthy track that lead singer/composer Michael Stipe described as “a male perspective on pregnancy, which I don’t think has ever been dealt with. There’s a real push me/pull you issue, saying ‘I had nothing to do with it.’ yet on the other hand saying, ‘Wait, I have feelings about this.’” In a sense, “Me in Honey” harkens back to the angst of some of the material from their early alt-rock days.

Yes, the songs in the R.E.M. catalog are often poles apart in mood and delivery. In his R.E.M. chapter, King recalls speaking with members of the Athens music scene in ’81 about the band’s appeal. One observer summed it up clearly: “They’re the only band that the artsy crowd and the frat boys both love.”

Usually King’s assignments had him covering artists whose records were climbing the charts (Jimmy Buffett, Atlanta Rhythm Section, the Marshall Tucker Band, the Allman Brothers Band, James Brown, Charlie Daniels Band Kenny Rogers, Lionel Ritchie, Willie Nelson, Dolly Parton, the B-52s . . .) or those who hadn’t scored any hits in recent years, but were on tour as perennial concert draws (Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, B.B. King, Tammy Wynette, Roy Orbison . . .). Then there were the acts assembling their repertoire and steadily gathering fans (R.E.M., The Brains, Sea Level, Amy Grant . . . ). Or, making the most of a two-hour getaway from Atlanta, King would travel to Pine Mountain, Georgia for the “Chet Atkins Country Gentleman Celebrity Golf Tournament” to chat with the legendary guitarist who, like Carl Perkins, was a major influence on The Beatles’ George Harrison.

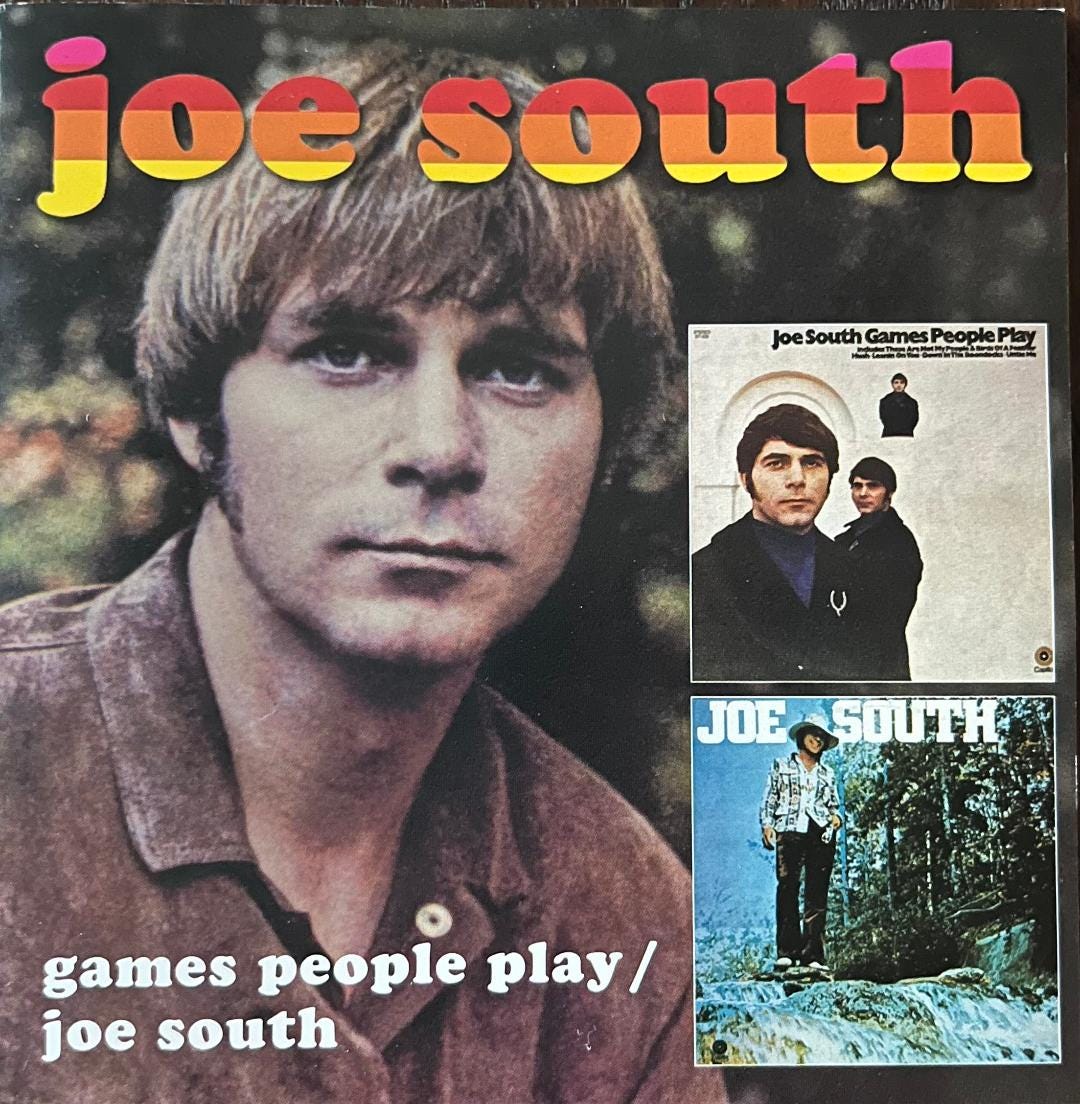

King’s encounters with his featured subjects were by and large upbeat and successful. The artists needed to promote themselves and King would proffer a question or drop a line that would get the subject talking, although few rolled verbally like James Brown. Always on the good foot and looking to score another comeback, Brown would say things that commanded the attention of readers as well as making himself the focus on any stage. It was easy for him, but not quite so for Joe South, also profiled by King in a thoughtful piece on a great artist who never regained attention from record buyers after being a popular and innovative presence from 1968 through 1970.

Though often overlooked, Joe South should be mentioned along with Blind Willie McTell, Johnny Mercer, James Brown, Ray Charles, Little Richard, Otis Redding, Gram Parsons, the Allman Brothers Band, and R.E.M. when considering the greatest musicians to come out of Georgia. He was a major talent.

South’s emergence in the music world is presented by King in what we used to call a Horatio Alger story. With the guitar he had gotten for Christmas, South, at the age of 12, visits WGST DJ Bill Lowery making a pitch to get on the air. Lowery, an avuncular gentleman always wanting to help folks, recalled for King that South wasn’t lacking for confidence. “He wanted to do a radio program, “Lowery said, “He said he wrote songs and he was great. I put him on every Saturday morning at 6 a.m.” That was 1952. It actually took more than a decade for South to approach greatness, but from ’65 through ’70, he was a steady presence on the nation’s airwaves.

In ’81, South told King how things — no matter how great — don’t come easy. He had moved to Nashville in ’62, looking to sell his songs and get on as a session musician in Music City.

"I had this song called ‘Down in the Boondocks,’” he said with a rueful grin, “and I walked the streets with that fucker for a year and a half, but nobody was interested.”

Three years later, back in Atlanta, South connected with his singer friend Billy Joe Royal, who was looking for the right song. He booked a session for Royal to record South’s “Down in the Boondocks” and “I Knew You When.” South was amazed at how his luck had changed, telling King, “The whole session cost $800.00 and took three hours. And both of those songs were million sellers.”

South produced the Royal tracks as well as producing other mid ‘60s hits such as The Tams’ “Hey Girl, Don’t Bother Me” and “Be Young, Be Foolish, Be Happy,” and “Reach Out in the Darkness” by Friend and Lover. In ’65, he played guitar on Simon and Garfunkel’s Sounds of Silence album. The very next year he appeared on Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde album, playing bass guitar on “Visions of Johanna,” and what Al Kooper called the “soul guitar” on “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again.”

The great R&B producer Jerry Wexler knew all about Joe South and his “soul guitar.” While producing Aretha Franklin’s Lady Soul album, he contemplated what would give the album’s lead-off track, “Chain of Fools,” an extra kick. In his book, Rhythm and the Blues, Wexler explained:

I’d brought up Joe South from Atlanta to play a special guitar part; we went for the Pop Staples sound by tuning the guitar down four or five steps and tuning the vibrato to the max, creating a deep mysterious tremolo.”

Released in November ’67, “Chain of Fools” climbed to #2 on the Billboard Hot 100 and all the way to #1 on the magazine’s Hot Rhythm and Blues chart. South’s sly and engaging guitar work provided a trademark sound to the song Wexler already thought “combustible.” Less than a year later, South’s Danelectro Guitar Sitar was heard on another hit record, his own “Games People Play,” from his debut album, Introspect, released on Capitol Records. South told King he knew “Games People Play” would be a hit and it was in spite of Introspect receiving little support from Capitol. “Games People Play” peaked at #12 on the Billboard Hot 100 and led off the newly configured Games People Play album Capitol released in place of the deleted Introspect.

For the next year or two the hits kept on coming. “Don’t It Make You Want to Go Home,” “Walk A Mile in My Shoes,” and “Children” all hit the charts and received much airplay. The Raiders had a hit with South’s “Birds of a Feather” while country singer Lynn Anderson had a mega crossover hit with his “Rose Garden,” both songs originally featured on Introspect.

Just as quickly, the hits stopped coming. Rolling Stone gave his ’73 album, A Look Inside, a glowing review, but the album didn’t chart. Two years later South recorded his Midnight Rainbows album for Island Records; it too was another fine effort that sat in the bins.

Joe South had loads of talent as a producer, composer, guitarist and vocalist. He possessed a rich and warm baritone. As with “Games People Play,” many of his songs were topical. Observant and disappointed with society, at times he came across like Howard Beale in the film Network: “An angry prophet denouncing the hypocrisies of our times.”

When Joe South sat down with Bill King in 1981, there was little to prophesy, but he could still look back at the last decade or so with bitterness and regret. Over iced tea and bread pudding at the Excelsior Mill, just northeast of Downtown Atlanta, he talked about struggling to make much money despite producing hit records for other artists and how life had gone since he slipped off the charts in 1970.

Personally things were falling apart for South. There was a marijuana bust in a suburban county south of Atlanta in ’70. The next year tragedy struck when South’s brother and drummer, Tommy South, took his own life. Joe was already dabbling in drugs; the loss of Tommy, his “pal and confidant,” was something he couldn’t get over, causing him to reach for the pills more often. He found it nearly impossible to revive his career and a surly attitude toward crowds in club appearances sure didn’t help things. Wanting to get away from it all, he moved to Maui for two years. Back in Atlanta, he slowly and erratically plotted a comeback. That didn’t happen, not even a planned show at the venue where he was talking with King for a profile in The Atlanta Constitution.

King’s chapter on South may be the best in Large Time. Here King presents an artist, no doubt far more accomplished than most of those he covered, who lost his way and who understood why. It’s a moving piece on a beloved artist who had fans rooting for that comeback. Maybe it wouldn’t have resulted in winning two Grammy Awards as he did with “Games People Play,” but there’s a feeling that if South felt people were pulling for him, he might have given us another collection of observant songs that would remind us how terrific rock music can be when the hypocrisies of our times are being denounced.

Bill King did a great job in covering the scores of top music acts during his years on the beat at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. The ’70s and ’80s were far-reaching for all genres of music in the South. There were big names, big personalities, and big hits. King puts us right back in those days, making Large Time not only a rewarding trip down memory lane for those of us who love the music but who also cling to the spirit and hopes of those years. Having known King for nearly five decades, I know he has even more great stories. Here’s hoping he shares them in another book soon.

*The official title for The Beatles’ “White Album” is The Beatles.

Interested in buying a copy of Large Time? Here’s how:

You can get a copy for $39.99 postpaid in the U.S. or $69.99 postpaid outside the U.S. Add $10 to the cost if you’d like a numbered, signed copy! Send a check, money order or credit card information to: The Goody Press Books, 3009 Delcourt Drive, Decatur, GA 30033. You also can pay via PayPal to goodypress@gmail.com, or via credit card at 404-713-6432. Address all inquiries to goodypress@gmail.com. For an order form or to read more about the book, go to https://beatlefan.com/book-store.