In 1979, the “slow train comin’ up around the bend” felt like judgment upon us all, especially those of us in the United States.

America, not even a decade out of Vietnam, was already learning about life in the post-Vietnam era. The learning curve was steep and expensive. America found it couldn’t pursue a war successfully in the jungles of Southeast Asia and was also learning its economic grip on the world wasn’t as tight as it was at the beginning of the ‘70s.

First, there was the Arab oil embargo of 1973-74, beginning less than seven months after US fighting forces left Vietnam. The embargo was in retaliation for America’s military support of Israel during the Yom Kippur War. Arab members of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) made sure the US lived with the consequences. Gas shortages occurred throughout the country during the winter months of 73-74 while the price of a barrel of oil increased as much as 400 percent. It’s interesting what happens when other countries try their hands at unfettered capitalism.

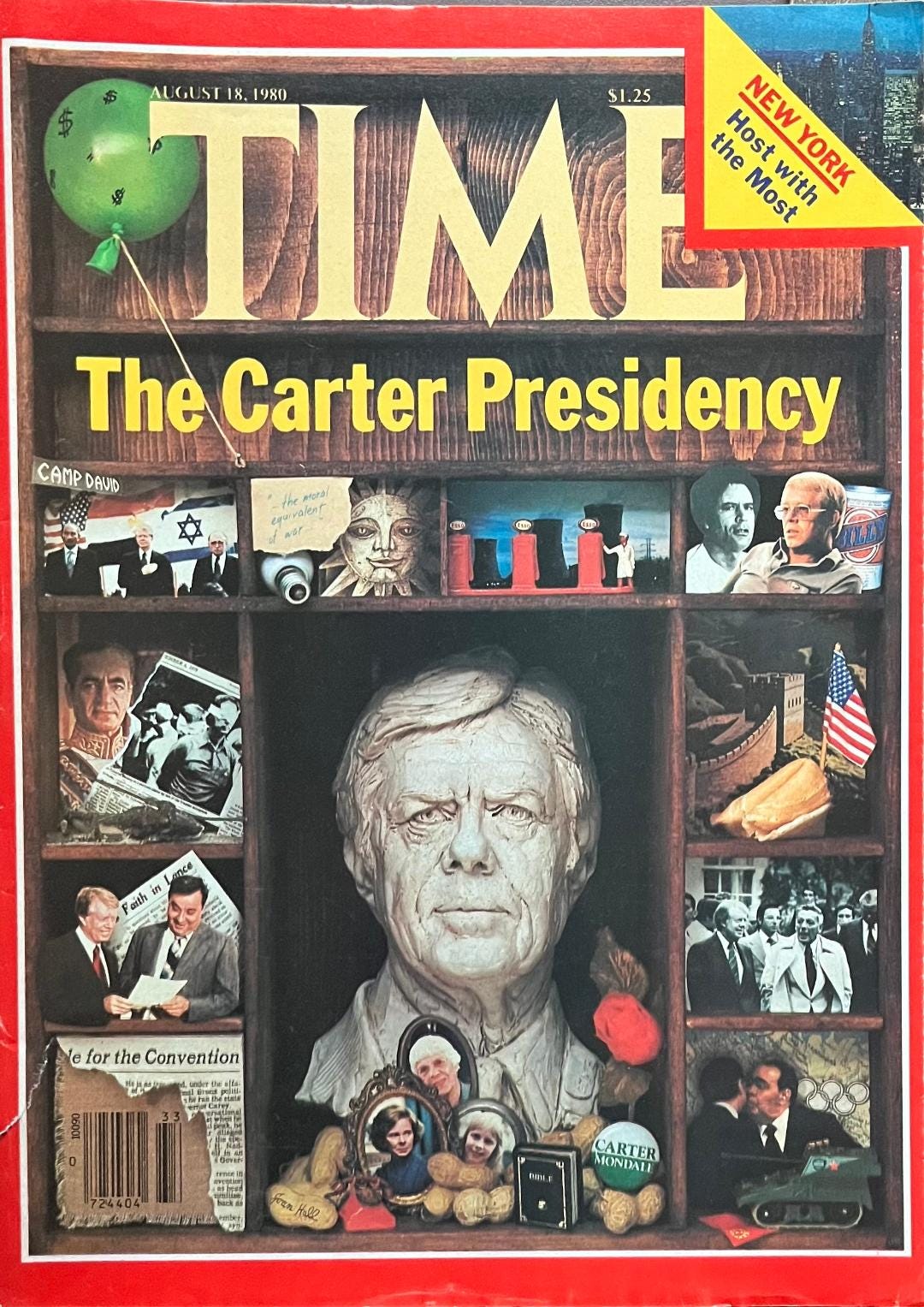

Less than six years later came the Iranian oil embargo. More revenge. More consequences. The aftermath of the Iranian revolution of ‘78 led to a drop in oil production. Availability of oil was better than in ‘73, but there were still long lines at the pumps. And when you bought gas in California, you did so on the even-odd formula allowing drivers with even-numbered license plates to buy fuel on even-numbered days while drivers with odd-numbered plates could purchase fuel on odd-numbered days. The concept was not successful and just added to the frustration drivers felt. Worse, prices increased again, with the price of oil doubling to nearly $40.00 per barrel. And higher prices for oil made all other prices climb. Such a crisis wasn’t what a visionary guy like Jimmy Carter thought he’d be dealing with as President of the United States. The American people were thrown off balance and angered by the turn of events. What’s with these smaller countries jacking up the price of oil the US needed for its economy?

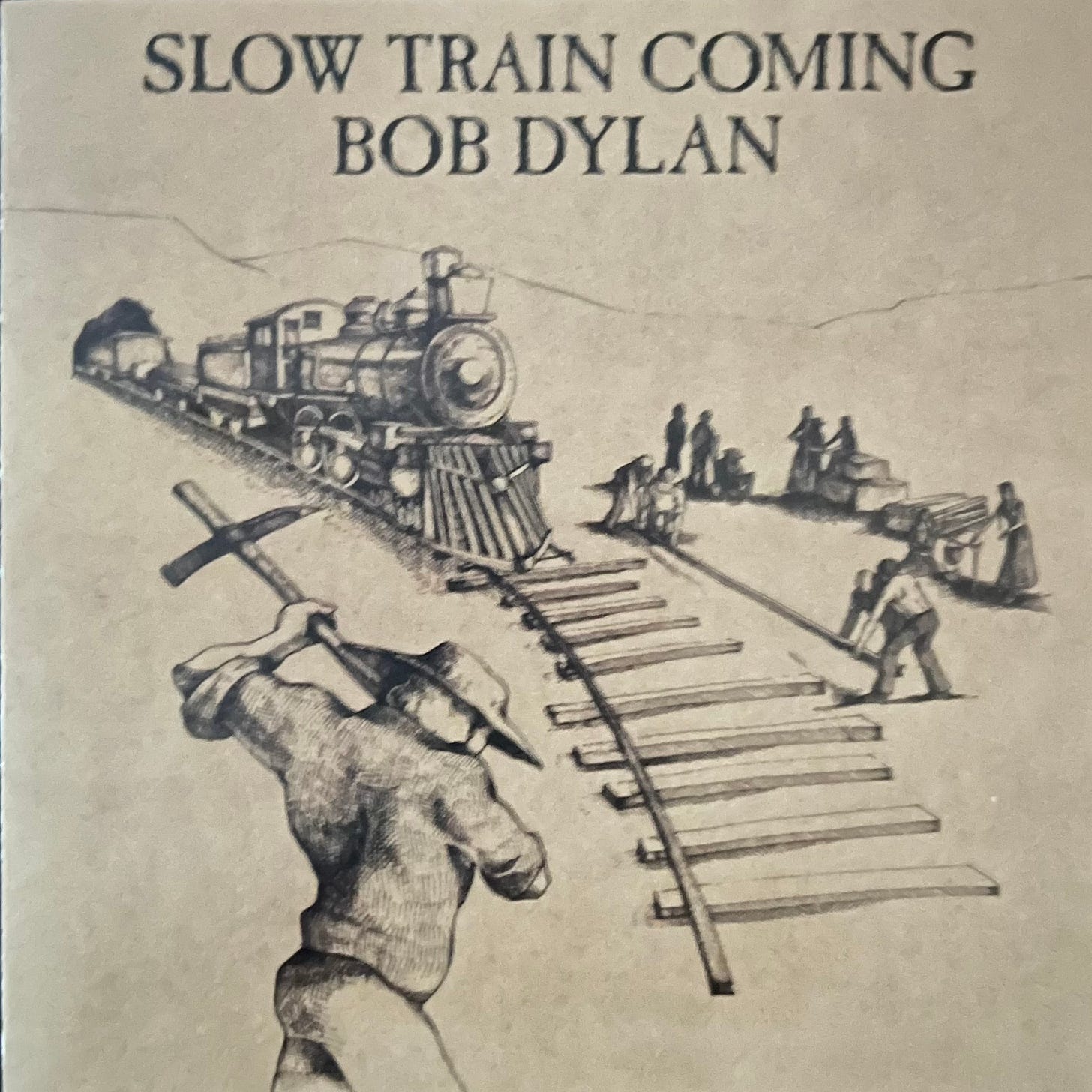

The American people’s anger over oil embargos and seemingly extortionary pricing even found its way into “Slow Train,” the most powerful track from Bob Dylan’s Slow Train Coming album, released in the late summer of ‘79. Most of the songs on the album dealt directly with Dylan’s new-found faith in Jesus Christ, but “Slow Train” intensely critiqued the powerful who ignored God, deceitfully pursued riches, and gave little thought to the needs of others. It’s a resolute song and it’s a discomforting song. In the Dylan style, there’s a lot of finger-pointing and the perspective was construed by some as nativist.

In the third verse, Dylan pulls no punches:

All that foreign oil controlling American soil

Look around you, it’s just bound to make you feel embarrassed

Sheiks walkin’ around like kings

Wearing fancy jewels and nose rings

Deciding America’s future from Amsterdam and to Paris

And there’s a slow, slow train comin’ up around the bend

Of course, there was little wonder why Sheiks felt like kings. They were maximizing their resources to build great wealth and they saw America, where the big companies showed little enthusiasm for building fuel-efficient cars, as the land of opportunity. Looking for cars that provided better mileage, a growing number of American buyers displayed new interest in the German-made Volkswagens and Toyotas from Japan, but in ‘73 those two makes combined sold less than one million units in the US, not even a tenth of the new cars sold by the American Big Three that year.

American automakers had long realized domestic car-buyers wanted longer, wider, and bigger, which most of their customers considered better. To drive their point home, they actually, in their roundabout way, convinced Americans they shouldn’t be producing small, fuel-efficient cars. In 1970, Ford began production of the Pinto while Chevrolet began rolling out the Vega. Those were bad cars. Dangerous cars. According to Mother Jones magazine, between 500 and 900 people died in Pinto crashes due to burn injuries. Motor Trend magazine called the Vega “a rust-bucket prone to gas-tank fires and melting engines.”

We could think of the automakers turning out such peril-on-wheels as like the “Masters of the bluff and masters of the proposition” Dylan called out in “Slow Train.” In the same verse, Dylan inveighs against “… the enemy I see” who “wears a cloak of decency” similar to the slick businessmen in their coats and their ties pushing what they claim are the greatest innovations American manufacturers have ever produced. Yes, they could still find ways to bluff their way into a customer’s pocket. I remember seeing a longtime friend in the fall of ‘70 a block or so from a Chevrolet dealer on the day the Vega made its showroom debut. My friend had his checkbook ready. One of the masters of the proposition had already gotten to him.

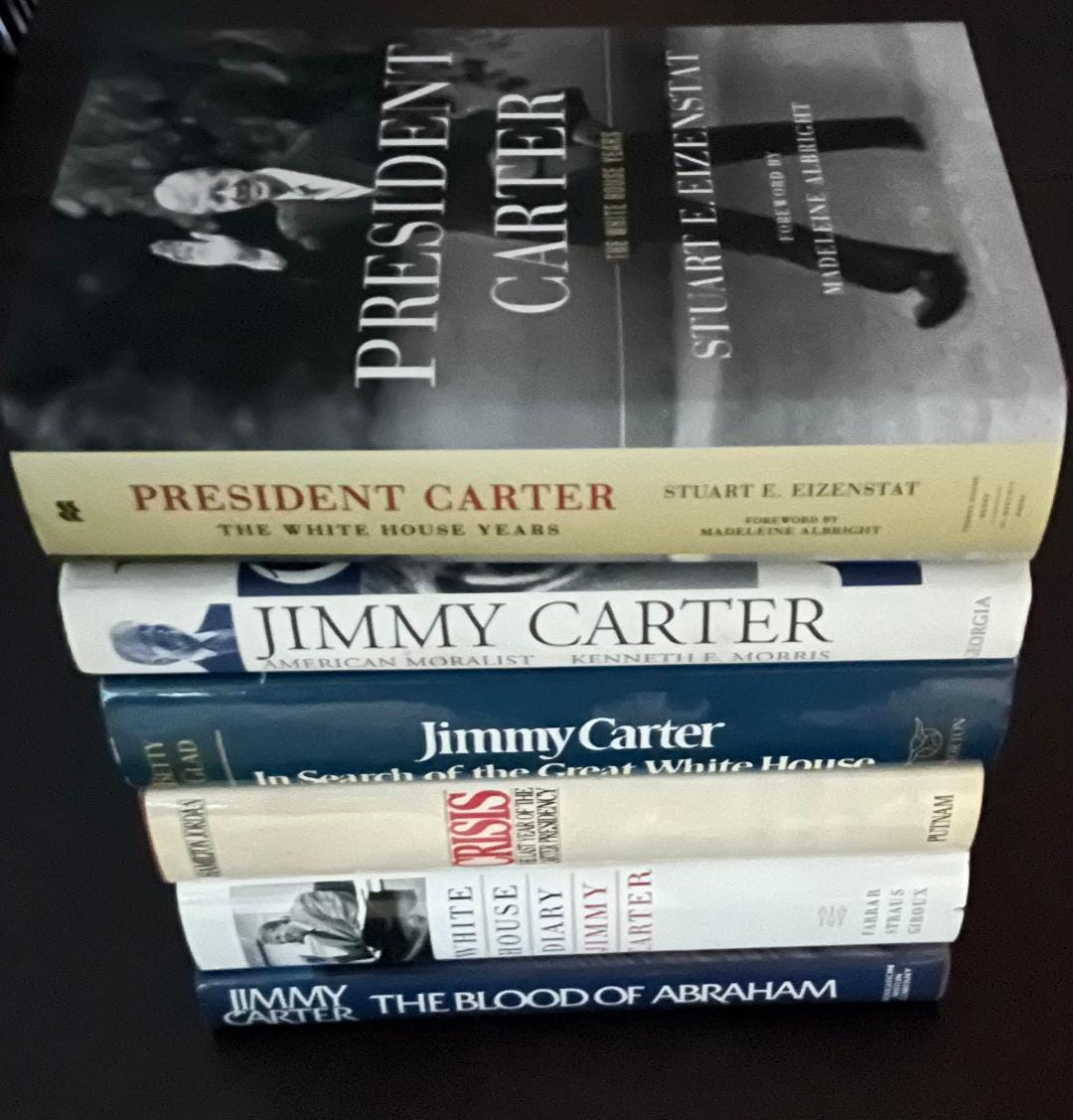

Early in his administration, even a year before the Shah hightailed it out of Iran, President Carter proposed that Americans think more clearly about their use of energy, which included the choices they made in automobile showrooms. During his single term as president, Carter gave six nationally televised speeches focused — at least in part — on the nation’s energy plight. On a simple and personal basis, it seemed Americans would give more thought to how much they were spending on the money pit known as the gas tank. Maybe Dad could’ve used some of the money he spent filling up the Buick on better food for his family. But it was a silly time in America, perhaps a sneak preview of our current sad state with Republicans getting political advice from the likes of Laura Loomer, young drivers commandeering busy roads and highways to conduct their own street races, and the continued focus on J. Lo’s heartaches.

In his excellent book on the Carter presidency in ‘79, “What the Heck Are You Up To, Mr. President?”, Kevin Mattson touches on the dull-witted culture that kept Americans from considering real problems that effected their lives:

When Carter went on television to give speeches to his fellow citizens about the issues of the day, few Americans bothered to watch. There were so many bread and circuses that distracted and that constituted the cultural vacuity of the 1970s: disco dancing, roller skating, hot tubs, mood rings, television shows like Charlie’s Angels and Three’s Company, a whole slew of fads and mindless diversions.

Perhaps Carter struck many Americans as a Cotton Mather type, piously demanding Americans eat their vegetables and stay away from the “social ramble,” baseball legend Satchel Paige’s term for the high life. But Carter was no prune-faced prude. He’d leave that for the Pat Buchanans of the world. However, his conscience guided him to advise the country not in the hope it would simply make his administration successful, but that it would also improve people’s lives — and improve life in the United States. Now in the evenings, Carter could give way to his joie de vivre, kick back with a little Scotch and listen to an Allman Brothers Band album or select from several of the most recent films from Hollywood. He sought enlightenment and kicks from every corner. When it was time to play, he played hard, knowing full well that on the next day he’d work even harder.

And no president, especially in the lives of the Baby boomers, would work as hard as Jimmy Carter. On January 1, 1979, he opened full diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, completing the work President Richard Nixon began in 1972. In ‘79, China had a population of nearly a billion people. It made sense that the world’s greatest economic and military power felt the need to communicate with such a country. For better and for worse, the China opening was the most sweeping foreign policy move by the US since World War II.

In the weeks after the opening, Carter hosted China’s Vice Chairman Deng Xiaoping at The White House, and on the first of February Deng and Carter visited Ford Motor Company’s Atlanta Assembly Plant in the southside suburb of Hapeville. That year, Ford ran commercials during televised NFL games proclaiming in song, “If you could see tomorrow the way it looks to us today, you’d say incredible.” Actually, you’d ask how much more money Ford had to burn as the company lost $3.2 billion from 1980 through 1982. The Atlanta Assembly Plant was no place for Deng to learn the finer points of capitalism, but whatever he saw did little harm to China’s economy. The Ford economy would thrive in the years ahead as well, especially in Hapeville, with the popular Ford Taurus and Mercury Sable being assembled there. From 1985 through 1991, over two million first-generation Ford Tauruses were sold. Americans obviously set aside any residual anger felt toward Ford over the Pinto. The American people are generally a patriotic bunch, at times extremely so, and they cheer on the nation’s successful enterprises.

But despite his success on several fronts, the American people were not cheering on Jimmy Carter. Hardly a month after he and Deng watched Fords being made, he brokered the second of two peace agreements between Egypt’s Anwar Sadat and Israel’s Menachem Begin. Carter worked relentlessly to bring peace to the Middle East; mentally the effort was the equivalent of lifting weights while doing sit-ups. But Carter wanted peace, no matter how unlikely the territory. Some presidents in our lifetime have boosted their popularity through war. Carter chose to seek peace. The moments in which he brought Sadat and Begin together can be remembered as triumphant, but not enough Americans felt pride in what Carter accomplished. Yes, there were other problems in the country, but here was a moment Americans could truly celebrate. If your memory serves you well, then you know that not enough of the 40,831,881 Americans who voted for Carter in ‘76 celebrated peace. Was peace in the Middle East just a Beltway story? There was no doubt more interest in (and opposition to) Carter’s call for nations to boycott the 1980 Olympics in Moscow to protest Russia’s invasion of Afghanistan. Indeed, as Kevin Mattson observed, cultural vacuity had taken hold.

Those more supportive of Carter could ruminate on the first verse of Dylan’s “Slow Train” and see it reflective of what was happening in America:

Sometimes I feel so low-down and disgusted

Can’t help but wonder what’s happenin’ to my companions

Are they lost or are they found

Have they counted the cost it’ll take to bring down

All their earthly principles they’re gonna have to abandon?

There’s a slow, slow train comin’ up around the bend

The slow train picked up speed. Republican nominee Ronald Reagan defeated Carter in his bid for reelection in 1980. Reagan’s campaign was often sloppy; he appealed to racists by kicking off his general election campaign in Philadelphia, Mississippi. He sided with those who desired the teaching of the biblical creation story in public schools. Reagan seemed to hardly have a grip on the diverse cultural forces driving America as it prepared to enter the last two decades of the 20th century, but with an actor’s skill, he had a knack for delivering the key line with impeccable timing. His most striking delivery came at the end of his and Carter’s nationally-televised debate one week before the election. With inflation still shredding American pocketbooks, he turned to the camera and addressed the audience, “Next Tuesday is Election Day. Next Tuesday you will go to the polls. You’ll stand there in the polling place and make a decision. I think when you make that decision it be well if you would ask yourself: Are you better off than you were four years ago? Is it easier for you to go and buy things in the stores than it was four years ago? Is there more or less unemployment in the country than there was four years ago? Is America as respected throughout the world as it was? Do you feel that our security is as safe? That we’re as strong as we were four years ago?”

Ouch. Reagan could’ve sat down right then and there. What he said the next minute or so hardly mattered. He had already connected. Those of us who supported and understood the methods of Carter’s policies would find little agreement with Reagan. We remembered his opposition to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, his declaring American involvement in the Vietnam War “a noble cause,” and his frequent calls over the previous dozen years to commit American military forces when the country would be better served with diplomatic measures. Then too was Reagan’s embrace of the American piety patrol who wanted the return of prayer and Bible study in the public schools. In so many ways it seemed a vote for Reagan indicated support for moving America backwards. However, a majority of Americans felt the country was stuck in neutral. Out of gas. There were few, if any, bright signs in the economy and there was also the matter of 53 Americans being held hostage in Iran over the previous year. This wasn’t Carter’s fault, but it was his predicament. We could be thankful, though, that on Reagan’s Inauguration Day, the Iranian government accepted Carter’s terms and all the hostages came home to the US, greeted by former President Carter, who carried with him an intense urgency that they make it back in a manner that promoted peace.

President Reagan would have his own episode with Iran, featuring delusional bad actors named John Poindexter and Oliver North. Americans could say they were better off materially, but not so morally and spiritually. Reagan’s election in ‘80 gave entry to the overly self-righteous and corrupt with no regard for liberty. Those people have no doubt regarded Reagan’s policies and demeanor as too soft. After all, he helped to end the Cold War. Those who crave power loathe the absence of war. That takes away fear, which those who make war thrive upon.

Reagan had some tough words for President Carter in that debate 44 years ago, but he kept it civil. Not once did Reagan call any of his opponents “a real dope,” “totally dishonest,” “crooked,” “dumb as a rock,” “a total flunky,” “lunatic,” “communist,” or “a nasty woman.” Those epithets, however, were hurled by the current Republican standard-bearer, and yes, Republican standards are in free-fall.

In the second verse of “Slow Train,” Dylan’s narrative focuses on a woman who had not seen much of the world but could surely see it was in trouble. Her plea is directed in a personal fashion, but it could be interpreted as her take of the world-at-large, especially its greatest power, the United States of America:

I had a woman down in Alabama

She was a backwoods girl, but she sure was realistic

She said, “Boy without a doubt

Have to quit your mess and straighten out

You could die down here, be just another accident statistic”

There’s a slow. slow train comin’ up around the bend

We can remember clearly enough how the nation looked when Dylan wrote “Slow Train” and how there have been moments of promise and peril since. Through much of this troubled century, America has seemed “another accident statistic,” facing hardships and upheavals barely imaginable in 1979: 9/11, the wars in Afghanistan and Iran, the muddle disguised as action in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the stock market crash in 2008, and worst of all, the emergence of a tyrant who as President of the United States has utilized fear as a political tool. That’s the president who told journalist Bob Woodward that “Real power is — I don’t even want to use the word — fear.”

Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 said “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” None of our first 44 presidents wanted the nation to live in fear. Neither does our 46th president. But the fear is palpable in 2024 as that slow train comes round the bend once more.

Also See:

Jimmy Carter Walks the Talk and the Slow Train Comes Around the Bend

Sometimes I feel so low-down and disgusted